Catholic Vancouver October 17, 2024

Archbishop Roussin offered first residential schools apology from Archdiocese of Vancouver: a century of Indigenous and Church relationship and reconciliation

By Paul Schratz

A continuing series looking at progress made in healing and reconciliation initiatives between the Archdiocese of Vancouver and Canada’s Indigenous peoples since their first encounter. This week, the Archdiocesan Synod’s recommendations on First Nations, and Archbishop Raymond Roussin.

Part 1. ‘Dialogue and sharing’: a century of Indigenous and Church relationship and reconciliation

In November 1998, Archbisop Adam Exner joined B.C. faith leaders in signing a statement supporting in principle the Nisga’a Treaty, giving the Nisga’a control over 2,000 square kilometers of land, self-government, and $190 million.

Archbishop Exner said he didn’t necessarily endorse all aspects of the agreement but he supported it in the interest of justice and because it was negotiated by all parties.

In 2001 the federal government started negotiations with the Christian churches on a compensation plan for settlements with former students claiming abuse. The government ultimately agreed to pay 70 per cent of the settlement costs.

The complexity of the issue of jurisdiction, responsibility, and vicarious liability was evident in two Supreme Court of Canada decisions in 2005. The court ruled the United Church of Canada was 25 per cent liable and the government of Canada 75 per cent liable for general damages in a B.C. residential school case involving sexual abuse.

In a separate ruling, the court ruled the Oblates of Mary Immaculate in B.C. were not vicariously liable for sexual assaults an employee carried out at another residential school because the employee in question had not been hired to supervise children.

In November 2005, an offer by 41 Catholic religious orders and dioceses was included in an agreement-in-principle to settle Indian residential schools abuse claims.

Described as an “historic milestone” by Assembly of First Nations National Chief Phil Fontaine, the $2-billion compensation package would give $10,000 to each of 86,000 residential school survivors, plus $3,000 for each year spent at a school. An advance payment of $8,000 would go to survivors 65 and over. The average age of former students was 60. The 41 entities would contribute $29 million in cash and real property and $25 million in “in-kind” contributions for programs such as Returning to Spirit, programs on self-esteem, programs for healthy mums and healthy babies, and other works the groups do in Aboriginal communities. The agreement settled the liability of the 41 groups in various class-action suits.

ARCHBISHOP ROUSSIN

Archbishop Raymond Roussin, SM, succeeded Archbishop Exner in 2004 and like his predecessor emphasized reconciliation with Aboriginal peoples.

In March 2004 he said his main goal for the Archdiocese was “that people become Christ-like,” developing “a personal spirituality which leads out to others in the realm of social justice and ecumenism.” Archbishop Roussin put his words into action by travelling to visit with elders and parishioners in Aboriginal communities such as Anahim Lake and the Bella Coola Mission. He also continued Archbishop Exner’s practice of meeting every two months with members of the Archdiocese of Vancouver First Nations Council.

The Archdiocesan Synod, which ended in 2006, paid special attention to the need for healing and reconciliation with First Nations Catholics and called on the Archdiocese to continue promoting such programs as Return to the Spirit. Archbishop Roussin wrote, “Faithful to our mission and the example of Christ Himself, we will not cease to promote reconciliation at every opportunity. I will look to the First Nations Council to continue its work between those communities and the Church.”

Under Synod Proposition 33, the archdiocese would “Initiate a richer dialogue and sharing with First Nations people at the parish, deanery, and archdiocesan level, in cooperation with the First Nations Council of the Archdiocese.”

Proposition 20 encouraged the use of programs such as Returning to Spirit which had a track record of bringing healing to native communities in other parts of Canada.

Shirley Leon, a member of the Chehalis Indian Band and co-chair of the archdiocesan First Nations Council, was one of five Aboriginal people invited to join the synod process.

Leon called the Synod report’s recommendations regarding First Nations “a concrete demonstration of Archbishop Roussin’s commitment to work with us, to find answers we need for our future.”

She expressed hopes it would light the way for a new model of participation in the Church, based on the synod’s call for both richer dialogue and sharing with First Nations people and healing programs.

Indigenous Catholics, she said, are at a point where they must choose alternative ways of being part of the larger Catholic community, rather than being part of mission-based communities that grew from the Oblates’ work.

“We need to move away from the mission model which existed largely under the Oblates of Mary Immaculate to another model of regular parish membership,” Leon said.

The presence of five Indigenous members on the synod was significant, she said. “It was one of the first times we have been asked to participate in helping to discern the future of the Church in Vancouver.”

Many First Nations members had been working on a new pastoral vision for their communities, and the synod was an opportunity to take things in that direction at the parish level, Leon said.

“Our people, in many cases, haven’t felt comfortable enough to join a parish apart from the missions, so I’m really excited about sharing these documents with both communities. I would also like to see the healing and reconciliation processes come alive, but first we need to have a vision of how we can become partners within the parishes.”

Programs that encourage healing and forgiveness for those “wounded by family and/or church personnel” can’t come too soon, she said, recalling the burial of a woman whose family had come together after her tragic death. While most had been away from the Church for various reasons, everyone found great comfort at the funeral Mass.

“When I see this kind of reconciliation, I am reminded of our need for programs so that there can be healing long before any tragedy occurs.”

In 2008 Archbishop Roussin made history when he issued the first official apology for residential schools on behalf of the Archdiocese of Vancouver. He made his remarks at one of the inaugural events of the national Truth and Reconciliation Commission, held at the University of British Columbia on March 5, 2008. In his remarks he noted there were five residential schools within the historical geographic boundaries of the Archdiocese of Vancouver over the years.

“Many good people came to residential schools and sent their children to residential schools,” he said.

“Although these schools involved many people who worked selflessly and honourably, the system itself was deeply flawed. Removing children from their culture and their families is a profound moral concern. It is especially painful to know that some children suffered sexual and physical abuse at the hands of their teachers and caregivers.”

As Archbishop of Vancouver, he said, “I express my deep regret and I apologize for any wrongs committed here. In Psalm 107 it states that those who are brought low through oppression, trouble, and sorrow will be raised up from their distress, and will gladly know of the steadfast love of the Lord, the great Creator. As we move forward, confident that only the truth will set us free and that reconciliation is the path to wholeness, I pray that the good Lord will direct all of us to healing and peace.”

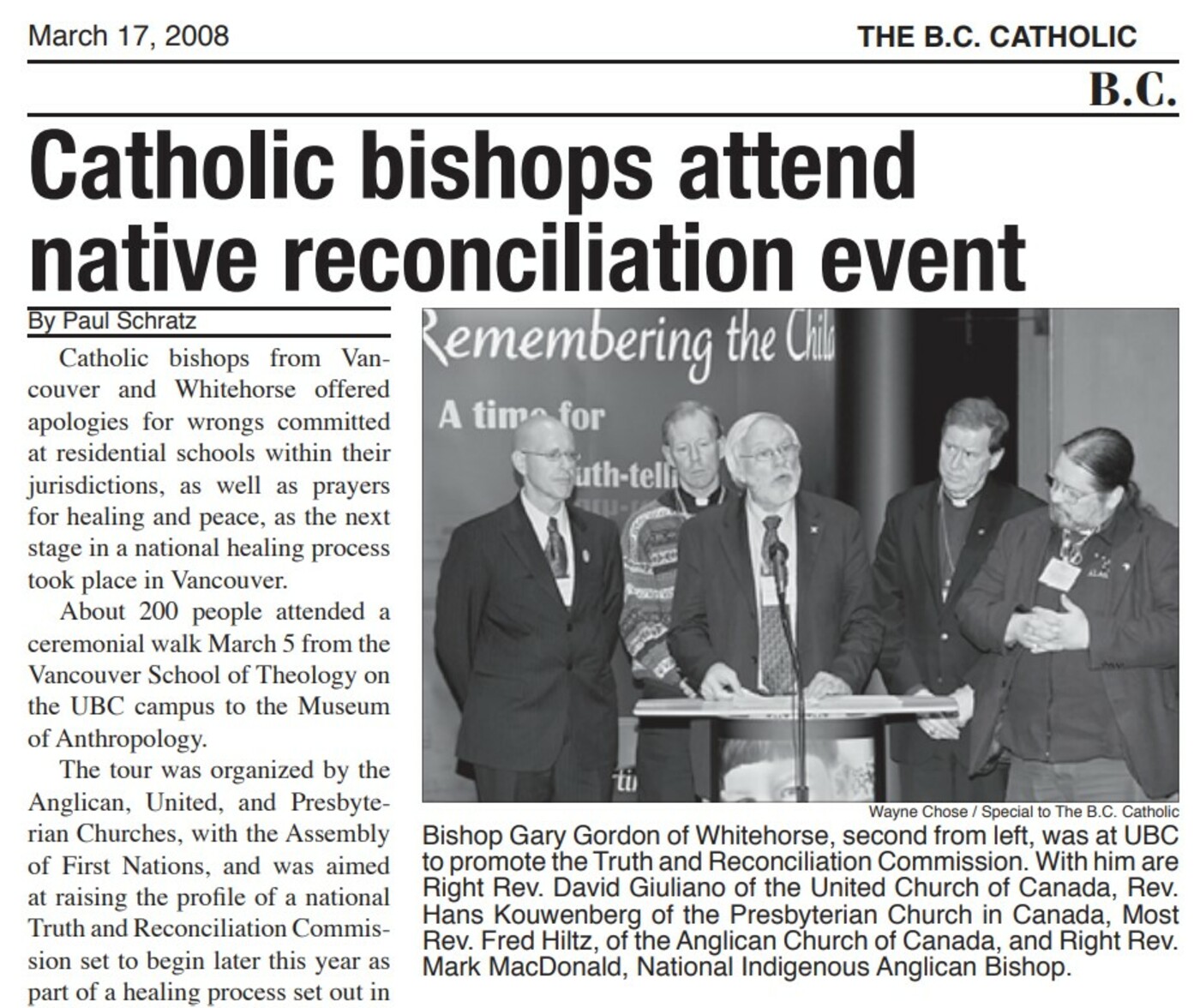

Later that month, Archbishop Roussin and Bishop Gary Gordon of Whitehorse, a former pastor to the Stó:lo in the Fraser Valley, promoted healing and reconciliation with Aboriginal peoples by participating in an ecumenical service at the Vancouver School of Theology in preparation for the upcoming Truth and Reconciliation Commission. They offered apologies for wrongs committed at residential schools within their jurisdictions, as well as prayers for healing and peace as the national healing process got underway.

In his remarks to the crowd, Bishop Gordon apologized to those who had suffered from attending the Catholic Lower Post School, which operated in the 1950s and 1960s near the B.C.- Yukon border. He offered particular apologies “for the sexual and physical abuse some of you suffered from some of the staff,” and to “all the students and families who suffered hurt to your culture and human dignity during the Lower Post era in the Diocese of Whitehorse.”

As for those students and families “who found some blessing in their experience at Lower Post, I thank God; and I am grateful to those staff who exemplified Christ’s love and care within a flawed education approach.”

Although the Archdiocese of Vancouver never operated a residential school, Archbishop Roussin attended the event to acknowledge that government/religious schools were run within the historical geographic boundaries of the archdiocese. Archbishop Roussin noted in his remarks that there were positive as well as tragic results. “Although these schools involved many people who worked selflessly and honourably, the system itself was deeply flawed,” he said.

“Removing children from their culture and their families is a profound moral concern. It is especially painful to know that some children suffered sexual and physical abuse at the hands of their teachers and caregivers. As Archbishop of Vancouver, I express my deep regret and I apologize for any wrongs committed here.”

Continued next week.

Your voice matters! Join the conversation by submitting a Letter to the Editor here.