Catholic Vancouver September 25, 2024

‘Dialogue and sharing’: a century of Indigenous and Church relationship and reconciliation

By Paul Schratz

The Easter Sunday signing of a Sacred Covenant between the Archdiocese of Vancouver and the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Kamloops First Nation was the fruit of months of dialogue between Indigenous and Church voices. They had observed the response to the startling events of May 2021 for three years, they could see what was lacking and they knew that a better way was possible.

Reports of possible remains of buried children on the site of a former residential school had led to speculation, incorrect information, and anger that threatened to destroy Church and Indigenous connections that had developed over generations. Spiritual and cultural bonds were being ruptured, and established friendships began to resemble strained interactions between strangers.

In 2006, Vancouver’s Archdiocesan Synod document Let Us Act called for the Archdiocese to “Initiate a richer dialogue and sharing with First Nations people.” In his synod declaration, Archbishop Raymond Roussin, SM, pledged to “promote reconciliation at every opportunity.”

The Archdiocese of Vancouver has been enriched in many ways through its relationships with First Nations, and despite the role the Church played in the residential school system, mutual efforts at understanding and respect have been taking place since the first missionary priests arrived nearly 200 years ago.

This is the story of the dialogue, sharing, and reconciliation between the Church and the Indigenous people from its origins in 19th-century British Columbia to the signing of the Sacred Covenant this year. Revisiting this history illustrates how relationships that had their origins over a century ago have become an important part of who the Archdiocese and First Nations are today.

The early history in this account draws heavily from the work of historian Jacqueline Gresko, who wrote Traditions of Faith and Service, the popular 2008 history of the Archdiocese of Vancouver.

The more recent history is largely from the pages of The B.C. Catholic, which has been reporting on the lives and interactions of Church and Indigenous members for nearly a century.

This is not a comprehensive history, but rather a story of encounter, apology, and efforts to rebuild relationships that continue to this day.

Part 1, The Pre-Modern Era

Until the end of the 19th century, British Columbia’s population was largely Indigenous, a people who were also long familiar with Christian beliefs introduced through trade and missionary encounters from the time of the arrival of the first missionary priests in the 1840s.

Over time, ecclesial structure came to British Columbia, and in 1846, the Diocese of Vancouver Island was created from the Apostolic Vicariate of Oregon. Soon, the Sisters of Saint Ann from Montreal and missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate from the Oregon missions would arrive to launch Aboriginal missions.

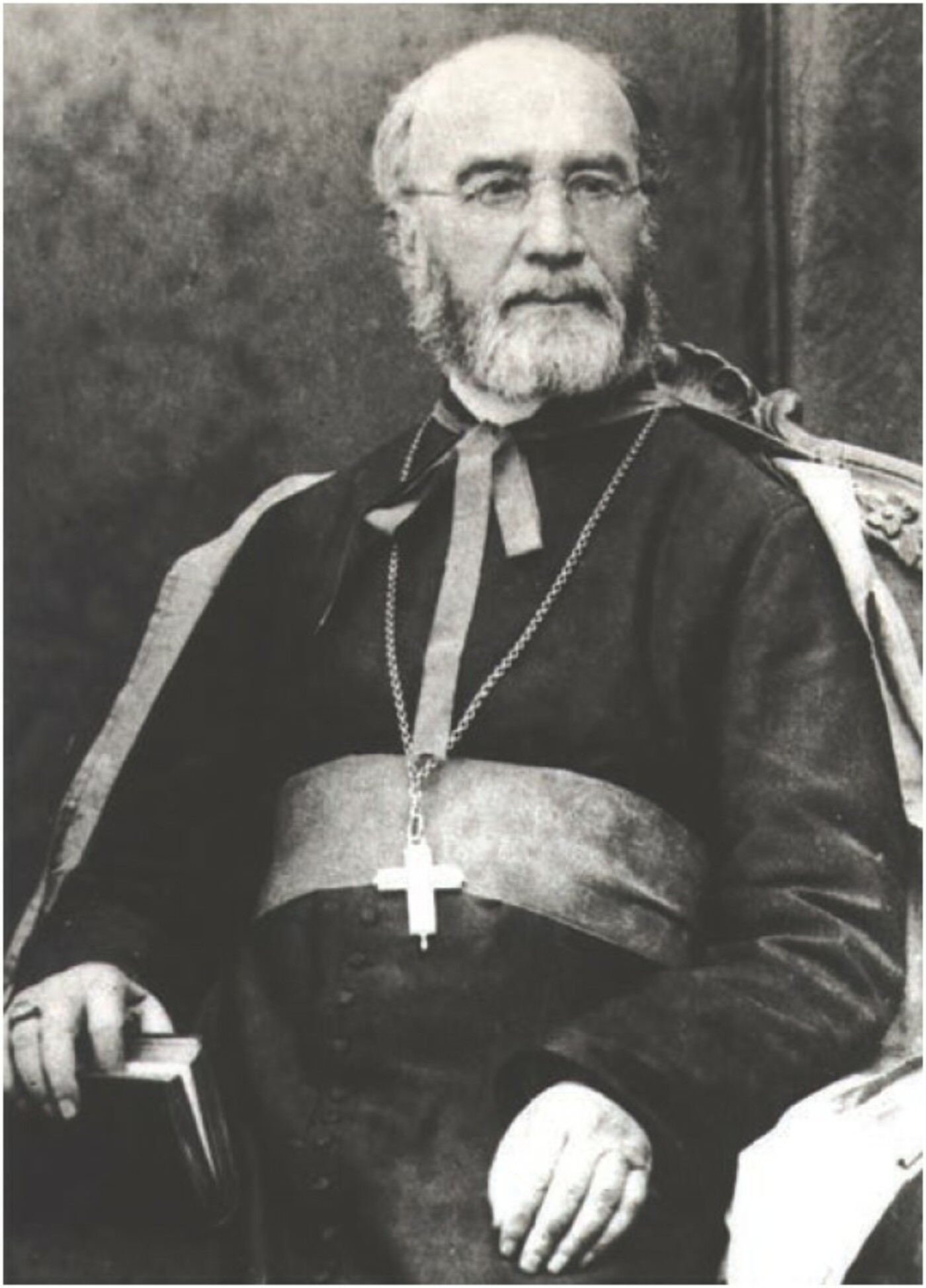

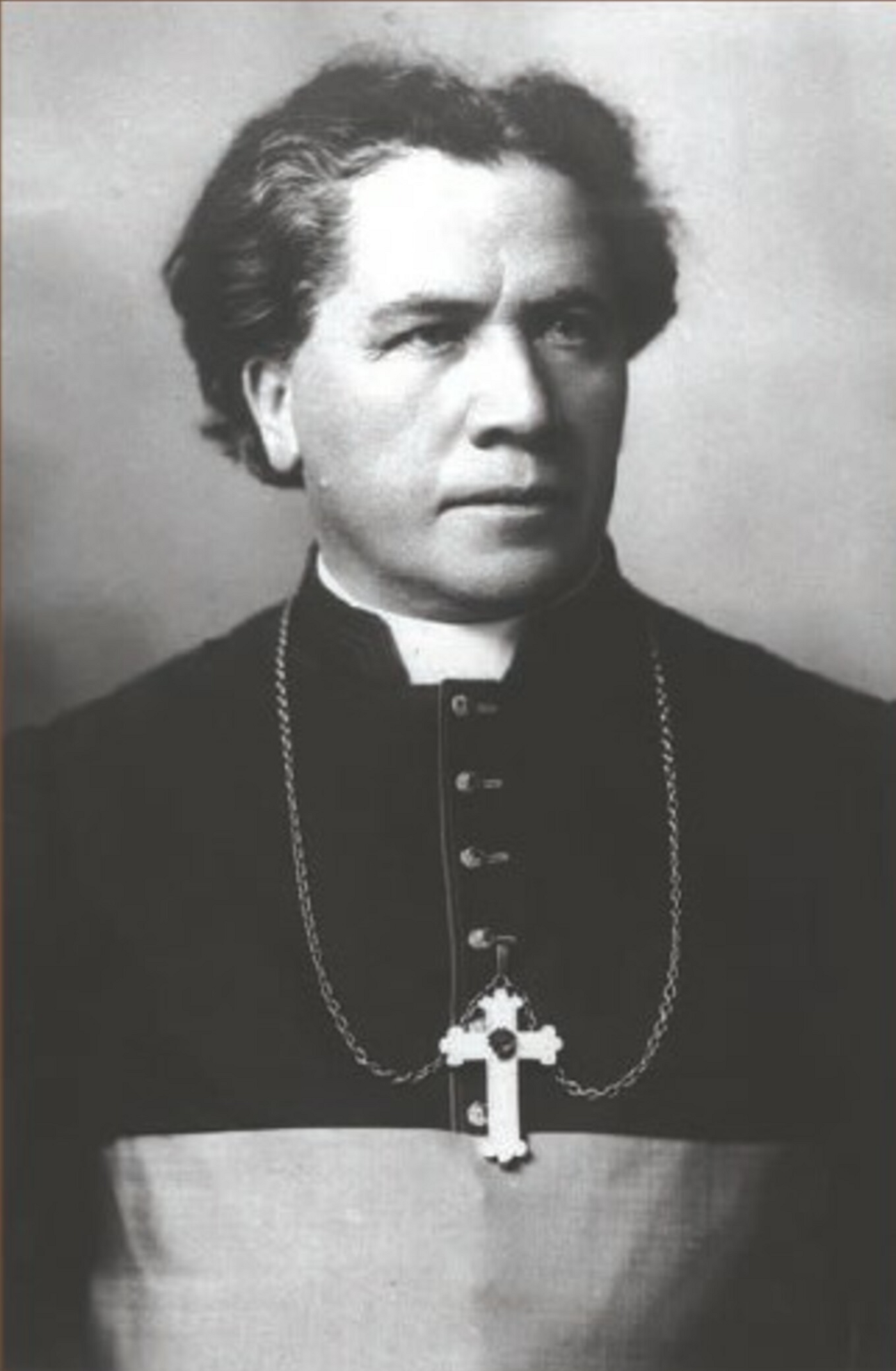

In 1863, Oblate local superior Father Louis-Joseph d’Herbomez became vicar apostolic of the new Apostolic Vicariate of British Columbia. In correspondence with his Oblate superiors, he outlined his plans for Aboriginal missions, plans that he shared with the federal government and which became part of an 1871 report on British Columbia.

The Oblates’ mission system would draw on their experience with Quebec and Jesuit missionaries in Oregon and look at ways of keeping Aboriginal peoples away from the vices of colonial towns, in particular liquor sales and prostitution.

The long-range goal was to establish agricultural villages modelled after Jesuit “reduction” communities for natives in 17th-century Paraguay. St. Mary’s Mission, established on the Fraser River east of New Westminster in 1861, with its chapel, school, farm and missionary residence, was regarded as a model mission, and from there, missionaries would set out for Aboriginal communities.

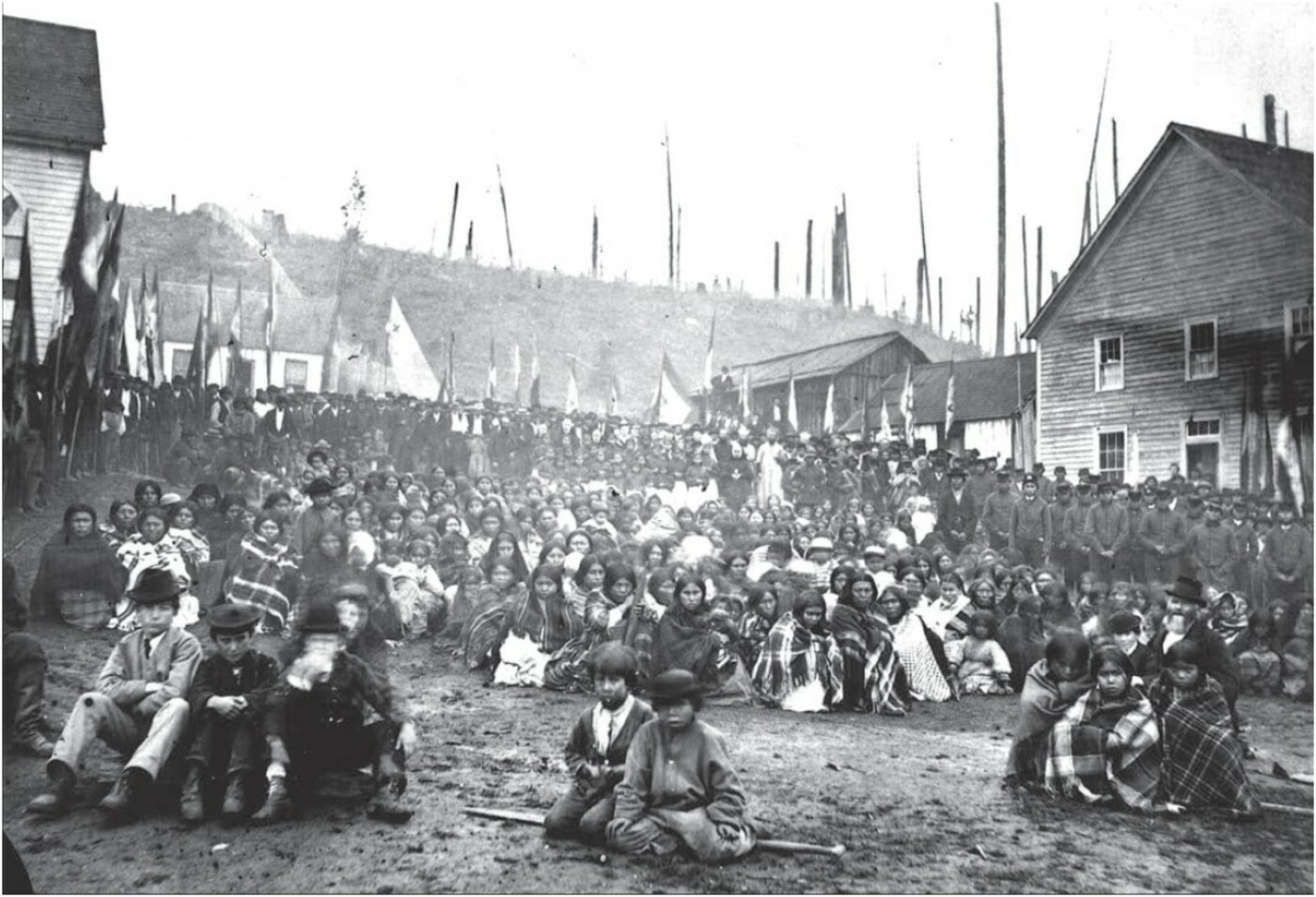

Between 1859 and 1878, the Oblates established missions in the Okanagan as well as in Squamish, Williams Lake, Sechelt, Fort St. James, the Kootenays, and Kamloops. The missionaries would hold well-attended annual gatherings to celebrate Catholic feast days and confirm the faithful.

The events drew Aboriginal peoples for religious as well as secular reasons, with the Oblates offering the local population services such as vaccinations against smallpox and assistance to chiefs writing land claim petitions in the 1860s and 1870s.

As Bishop d’Herbomez aged, his assistant Father Paul Durieu, OMI, took on the administration and field supervision of the Aboriginal missions. He replaced Bishop d’Herbomez when he died in 1890 and became the first bishop of the newly elevated Diocese of New Westminster.

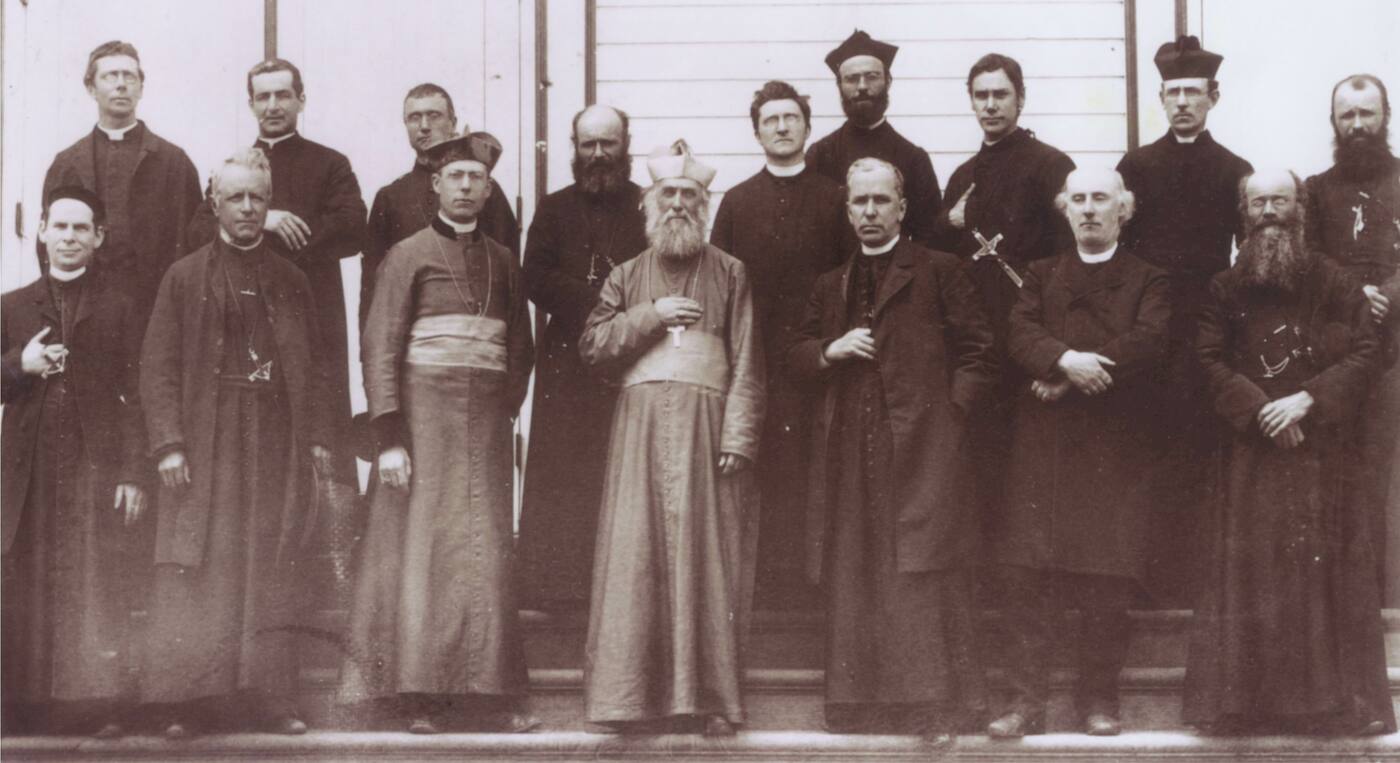

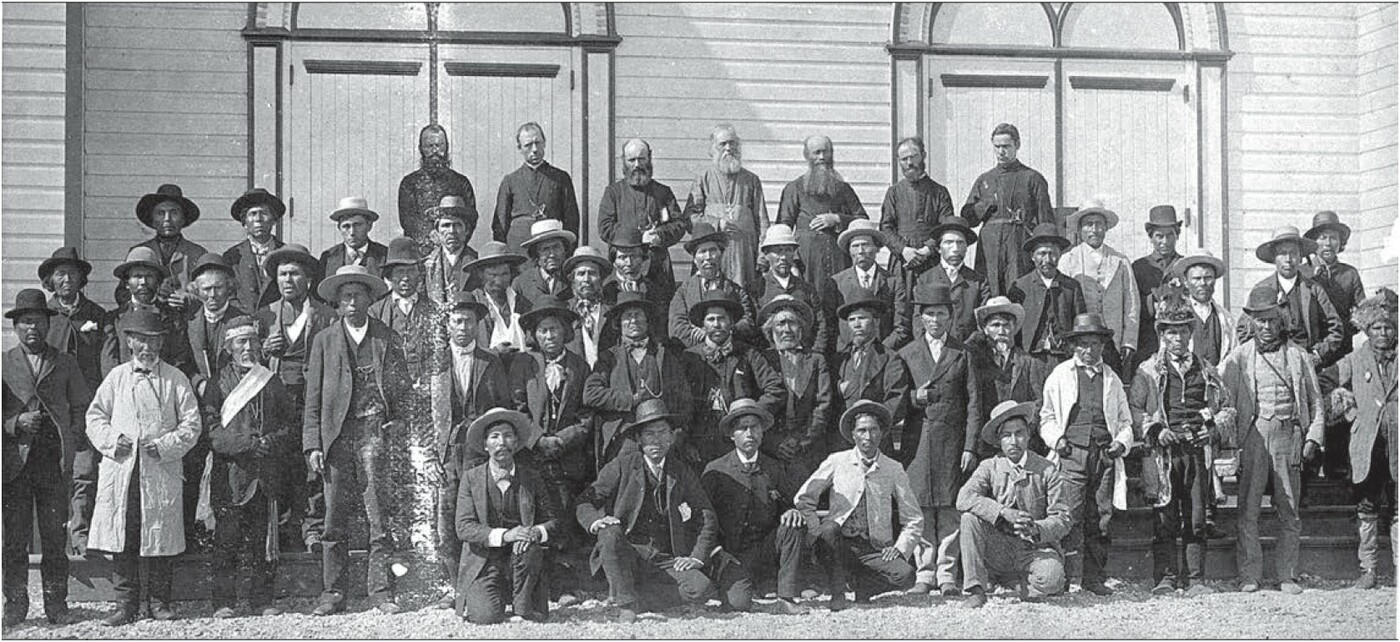

Bishop Durieu expanded the annual Aboriginal mission gatherings, bringing together thousands of Indigenous people at St. Mary’s, and then Squamish, Sechelt, and Kamloops. Aboriginal leaders assisted the Oblates with the organization of the events, which featured Aboriginal languages as they promoted Catholic devotions and lay organizations. At that time, two dozen priests and a dozen lay brothers were serving 70 Aboriginal village churches as well as the growing immigrant population.

In 1899, Bishop Augustin Dontenwill became bishop of New Westminster and altered the diocese’s Aboriginal direction, moving away from its emphasis on scattered missions and instead toward centralizing and consolidating them, as with Oblate missions elsewhere in Canada.

Bishop Dontenwill arranged for experienced field missionaries to serve the Carrier people in the Central Interior and to meet their requests for education. He assigned the first resident priest to the Sechelt mission in 1904 and supported Father J.M. Le Jeune, OMI, missionary to the Secwepemc (Shuswap) at Kamloops, in taking a delegation of chiefs to the Vatican. Father Le Jeune became known for his publication of the Kamloops Wawa, a journal written in Chinook and English. Each issue had articles on religious topics and news of Secwepemc communities.

Bishop Dontenwill stressed the need to provide services to immigrant as well as Aboriginal populations, particularly education. With a shortage of priests, he encouraged the work of women religious in the diocese in education, health care, and parish work.

In 1908, the Diocese of New Westminster became the Archdiocese of Vancouver and Archbishop Dontenwill was elected as Oblate superior general in Rome. Until the appointment and installation of Archbishop Neil McNeil in 1910, Father John Welch, OMI, administered the Archdiocese of Vancouver. His term was a period of continuity and change. He served as Oblate provincial as well as archdiocesan administrator, supervising 40 Oblate priests and brothers in Aboriginal missions and schools and nine Oblate and secular priests in parishes for settlers.

Most of the province’s Catholic population at the time was Aboriginal, and Father Welch and the Oblate congregation faced challenges in trying to staff existing Aboriginal missions and new parishes while spreading the faith to the non-Catholic majority of the settler population.

The organization of the Catholic Church Extension Society in 1908 resulted in English Canadians joining the missions to Aboriginal peoples and rural settlers in British Columbia. In 1909, the Oblates reorganized their work in the Archdiocese of Vancouver, considering it part of an English-speaking province in Central and Western Canada. Increasingly, Irish-Canadian Oblates from Ontario would come to the territory.

During the episcopacy of Archbishop Timothy Casey (1912-1931), the Aboriginal population of the province was about 60 percent Roman Catholic, but it was spread far and wide geographically and consisted of diverse cultural groups. The Oblate superiors remained short of priests to visit missions or staff residential schools.

Several federal government residential schools for Aboriginal children were established in the Archdiocese of Vancouver. Some schools, like St. Mary’s Mission school, were staffed by Oblates, and Archbishop Casey would visit the schools once a year for confirmation.

Through the late 19th century, a drastic decline in Aboriginal populations occurred as infectious diseases from Europe and Asia overwhelmed First Nations. “When these epidemics struck, people died in such mass numbers that it was a common occurrence for bodies to remain unburied,” according to B.C.’s First Nations Health Authority. The newcomer population gradually became the overwhelming majority in B.C.

Gradually, as Aboriginal numbers started to recover, they began moving from rural reserves to urban areas and from residential schools to integrated education. Until the 1930s, new arrivals to the province, such as Asian immigrants, would be considered minorities, and, like the Aboriginal and Métis peoples, they experienced increasing racism.

Archbishop William Mark Duke showed particular respect for Aboriginal Catholics as he travelled to their communities, including difficult-to-access places such as the Church of the Holy Cross at Skookumchuk (Skatin). That respect was communicated to the larger Catholic community, and in 1938 he blessed a cross at the Eayem reserve cemetery near Yale bearing the inscription: “Erected by the Stallo Indians to the memory of many hundreds of our forefathers buried here. This is one of six ancient cemeteries within five miles of fishing grounds which we inherited from our ancestors. R.I.P.”

After the Second World War, Archbishop Duke contributed to Aboriginal education by supporting the Anahim band’s wish for the development of on-reserve day schools, while most local Oblate administrators focused their efforts on the Cariboo residential school.

Irish Oblate Father Fergus O’Grady supported Archbishop Duke’s education initiative and served at several Native residential schools in the Interior. The future Prince George bishop’s main focus was the Oblates’ role in Native education and he became responsible for two projects that furthered the integration of Aboriginal students: the recruiting of Frontier Apostles, a “peace corps” of lay and religious volunteers to build and staff 12 schools; and the establishing of Prince George College.

In the post-war period, the Sisters of Saint Ann who taught in Aboriginal residential schools at Kamloops and St. Mary’s Mission pioneered high school programs for Aboriginal youth. The Kamloops sisters also worked on the integration of First Nations students in St. Ann’s Academy classes in Kamloops.

Next week, Part 2, Archbishop Carney and the Modern Era.

Your voice matters! Join the conversation by submitting a Letter to the Editor here.