Catholic Vancouver June 27, 2024

Archdiocese and First Nation pledge ‘meaningful steps towards healing’ through Sacred Covenant

By Nicholas Elbers

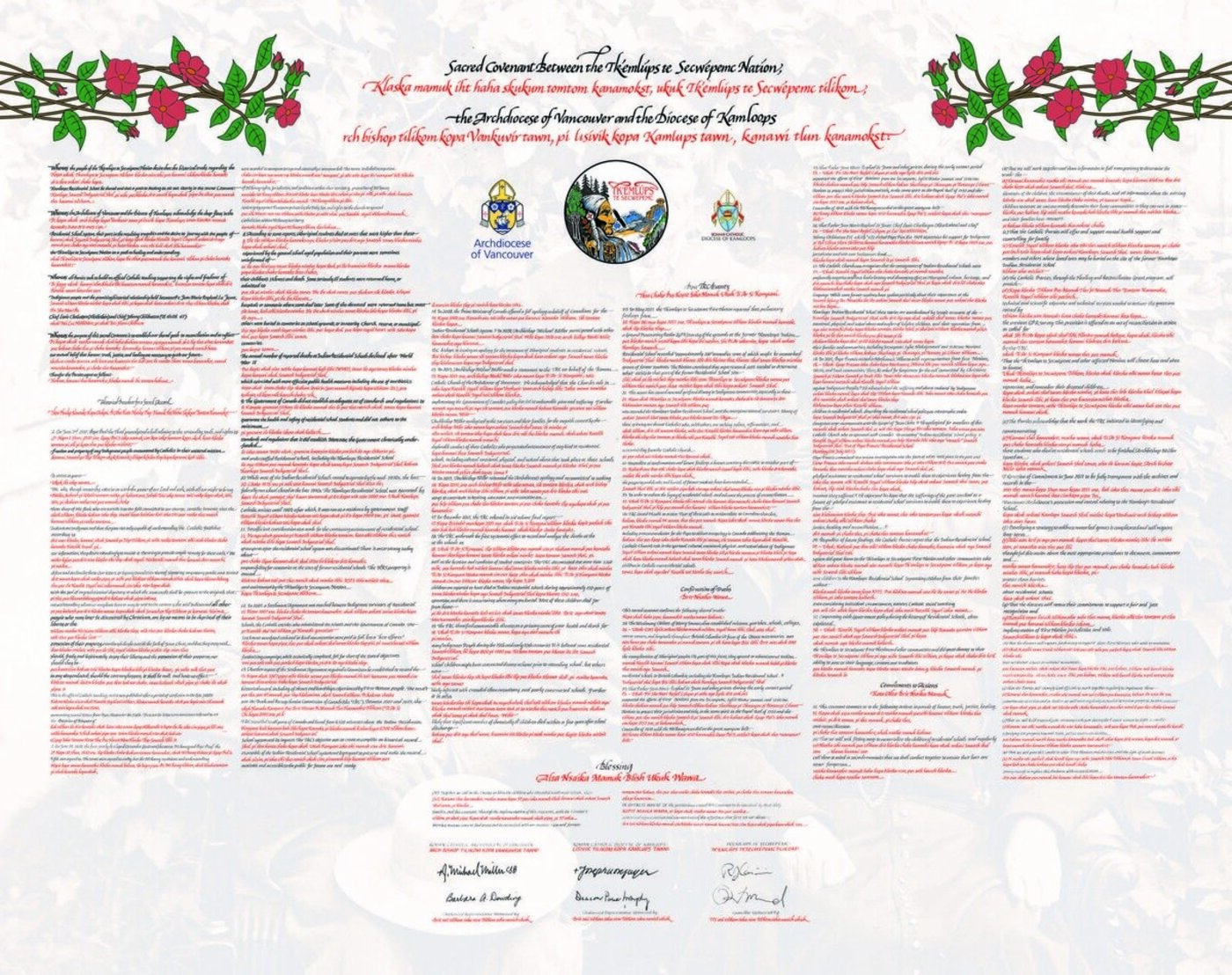

Looking to the future with hope was the clear message presented by the Archdiocese of Vancouver and the Kamloops First Nation (Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc) as the two signatories of the Easter Sunday Sacred Covenant held a press conference Wednesday.

The full document was released in English and Chinook for National Indigenous Peoples Day, June 21, with a promise to answer questions at Wednesday’s press conference.

Archbishop J. Michael Miller and Kamloops Chief Rosanne Casimir addressed the release of the covenant, saying they are committed to focusing on the future and moving forward together.

The covenant “affirms that all the signatories seek to build on official Catholic teaching support” for the rights and the freedoms of Indigenous people, said Casimir.

“It’s about relationships,” she said. “It’s about making some meaningful steps towards healing. We can’t do that alone, we have to do it in partnership.”

Answering a reporter’s question about whether the covenant has set a precedent for future engagement between the Catholic Church and Indigenous communities, Casimir said she believes “that it sets a lot of precedents.”

“We also need to take those meaningful steps to provide opportunity for those to find justice, but also to find healing. It takes everybody at every level to be walking that path and journey together,” she said.

“I would encourage others to build and establish those relationships to take those meaningful steps,” said Casimir.

Archbishop Miller agreed, saying Canada’s bishops are looking for ways to make the covenant a possible template to help the Church “enter into healing relationships with the First Nations communities of which they form a part. We have a lot to do.”

He reiterated the acknowledgement of harm to the First Nation from the Indian Residential School system. “The Church was wrong in how it complied in implementing a government colonialist policy that resulted in the separation of children from their parents and their families. Even the most ardent skeptics must know that a system requiring or pressuring the separation of families would have tragic consequences.”

In answer to a question about making possible financial reparations, the Archbishop said that while the covenant is meant to help heal the spiritual and communal rift between the church and First Nations, monetary support is ongoing across the country through truth and reconciliation grants, with nearly 20 approved in the Archdiocese of Vancouver.

The initiatives are all Indigenous led, said the Archbishop, and “generated by requests from the Nations themselves, not us. It’s not things we think should be done, it’s a response to what a nation puts forward as something they would like to see done to further healing and reconciliation.”

Casimir said that the various Indigenous stakeholders will “choose how and when to honour, repatriate and remember their deceased children.”

During the press conference, Casimir addressed the Kamloops First Nation’s findings of three years ago at the site of the former Kamloops Residential School. She said results of ongoing research are “consistent with unmarked burials,” referring to what had been described as children’s “remains” three years ago now as “anomalies” and as “the children who did not go home.”

The shift of language was noted by National Post writer Terry Glavin in a recent column where he observed that the First Nation used the term “anomalies” rather than “remains” in an announcement of a Day of Reflection to commemorate the third anniversary.

On May 27, Casimir released a statement, Reflections on the Third Anniversary of Le Estcwicwéy̓ (the Missing), in which she said, “In May 2021 with the assistance of a Ground Penetrating Radar, Tḱemlúps te Secwépemc was able to narrow down the location of probable unmarked burial sites on the grounds of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School (KIRS).”

Similar language appears in the Sacred Covenant, which refers to preliminary GPR findings of “roughly 200” anomalies, “some of which might be unmarked graves of former students.”

The covenant says more research is required “to determine what exists in that part of the former residential school site,” a point also made in the May 27 statement, which includes an update that, “We are taking steps to ensure the investigation is carried out in a way that does not preclude and will not interfere with potential future legal proceedings.”

Casimir said the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc researchers are immersed in “multi-disciplinary investigation,” employing “archival and documentary research and analysis, Wenecwtsínem (truth telling) with KIRS survivors, archaeological and anthropological surveys and studies, and potential DNA and other forensic methods.”

All the findings to date and the step-by-step process are currently being kept confidential to “preserve the integrity of the investigation,” said Casimir.

She explained the reasoning behind the change in language, saying the decision was informed by how GPR specialist Dr. Sarah Beaulieu identified her findings and by history.

Regarding “what was presented at the Coast Canadian Inn [in 2021] when we had Dr. Sarah,” said Casimir, “she also confirmed the anomalies. But it was also the historical details and oral histories that also spoke truth to the potential gravesites of the children that did not go home. It was those truths, and they were always kind of identified as anomalies, but also identified as the children who did not go home.”

The covenant recognizes that “developing a strategy to address unmarked graves is complicated and will require long-term thoughtful discussion about the most appropriate procedures to document, commemorate and protect those burials.”

The two B.C. dioceses – referred to jointly throughout the covenant as the “Catholic Parties” – pledged to support these efforts.

Though the Sacred Covenant said some “former students have spoken positively about their experience at the Kamloops Indian Residential School,” it says such cases were overshadowed by the negative.

Casimir and Miller both identified the commitments to actions section as the true heart of the Sacred Covenant. The major efforts to be undertaken going forward include:

- Seeking honourable ways to memorialize the children of residential schools;

- Working together in transparency to determine the truth: “the identities of the children, the circumstances of their deaths and all information about the missing children to ensure we can accurately determine their home communities so they can rest in peace and their families have answers”;

- The Catholic Parties pledge to provide mental health support and family counselling for loved ones and others who may be buried on the former KIRS grounds;

- That the dioceses arm Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation with expertise and technical services to help answer questions raised by previous GPR work;

- Dioceses support fundraising for First Nations who seek to maintain their former residential schools as national monuments.

With files from The Catholic Register