Catholic Vancouver October 14, 2021

After Kamloops: ‘We did not listen then ... will we listen now?’

By Anastasia Hurcum

As the country was rocked with the discoveries of hundreds of unmarked graves on residential school properties, Canadians were shocked and angry. They asked themselves: what do we do?

An answer came in the form of a lecture entitled After Kamloops, the Flood, presented by the Centre for Christian Engagement at St. Mark’s College.

Debra Sparrow, a member of the Musqueam First Nation, opened the Oct. 1 event with a story of her childhood. As a child she desired to enter a convent, until an incident involving a wrongful accusation of theft inspired her father, a residential school survivor, to remove her from Catholic school and continue her schooling elsewhere.

But Sparrow’s mother taught her to always be accountable. “We are living through difficult times,” she said, “and we need to be accountable for our actions”

Sparrow also spoke of reconciliation and of how everything is connected. In God’s eyes, all people are different pieces of a beautiful tapestry and have gifts that complement others. Yet, she said, we live in a world where no one gets along.

She offered a gentle call to action: “Now, we must listen. There are so many people in different stages of healing, with years and years of painful stories to tell. So now we must listen and listen well.”

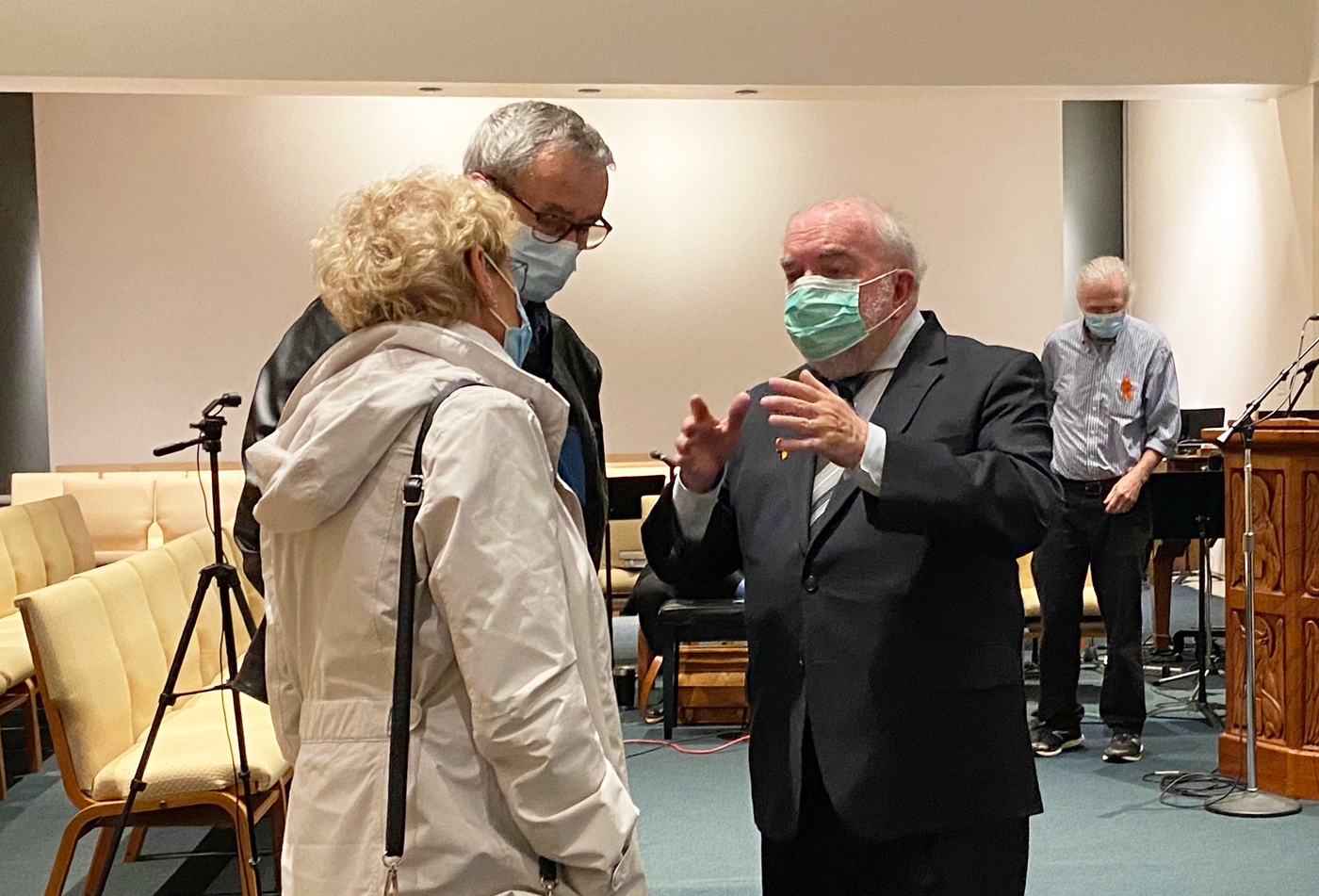

On the podium, St. Mark’s College interim president and vice chancellor Dr. Michael W. Higgins began the lecture portion of the event by explaining that in the past, Indigenous people experienced great abuses by members of the Catholic community, and that the Church is now committed to the process of healing and reconciliation. He said the work on this subject has just begun.

Speaking to about 100 in-person and livestream viewers, Higgins highlighted the wrongness of the treatment suffered by Indigenous people at the time. Children were ripped from their families, forced into government schools, and made to conform to a manner of existence deemed acceptable by Catholic and government authority figures, in the process suffering mental, physical, emotional, and sexual abuse.

Years later, after the cumulative horror upon finding unmarked graves, Higgins asked the question: “How did we not know this? We were told so many times.”

He then noted, “We did not listen then ... will we listen now?”

Higgins echoed Sparrow’s sentiment that there is “no path forward without reconciliation” through examination of faith, acknowledgement, and the speaking of truth.

He quoted award-winning poet and former Jesuit seminarian Tim Lilburn, who said Catholics must identify what attitudes in Catholicism were responsible for the residential school culture. “These dispositions, missiological, ecclesiastical, spiritual, interpersonal, and the thought-worlds backing them up, must be purged.”

Higgins said such deeply uncharitable attitudes kept settlers from loving their neighbours in their differences, are uncatholic, and must be purged.

He also referred to Irish mythographer John Moriarty and Trappist monk Thomas Merton, who Higgins described as kindred spirits.

The two men seemed to agree that a key to healing relationships with Indigenous people is Catholic intellectual tradition, a reconciling of faith and culture in search for truth in all aspects of life.

Moriarty and Merton believed the Catholic intellectual tradition laid out hopes for truth and reconciliation. Catholics, they taught, must question themselves, their beliefs, and their actions and come to the truth that we are all one human family despite racial, national, ethnic, economic, and ideological differences.

Then, said Higgins, Catholics must take on the future and the issues around us with the compassion – the love for others despite our differences – that our forefathers seemed to lack.