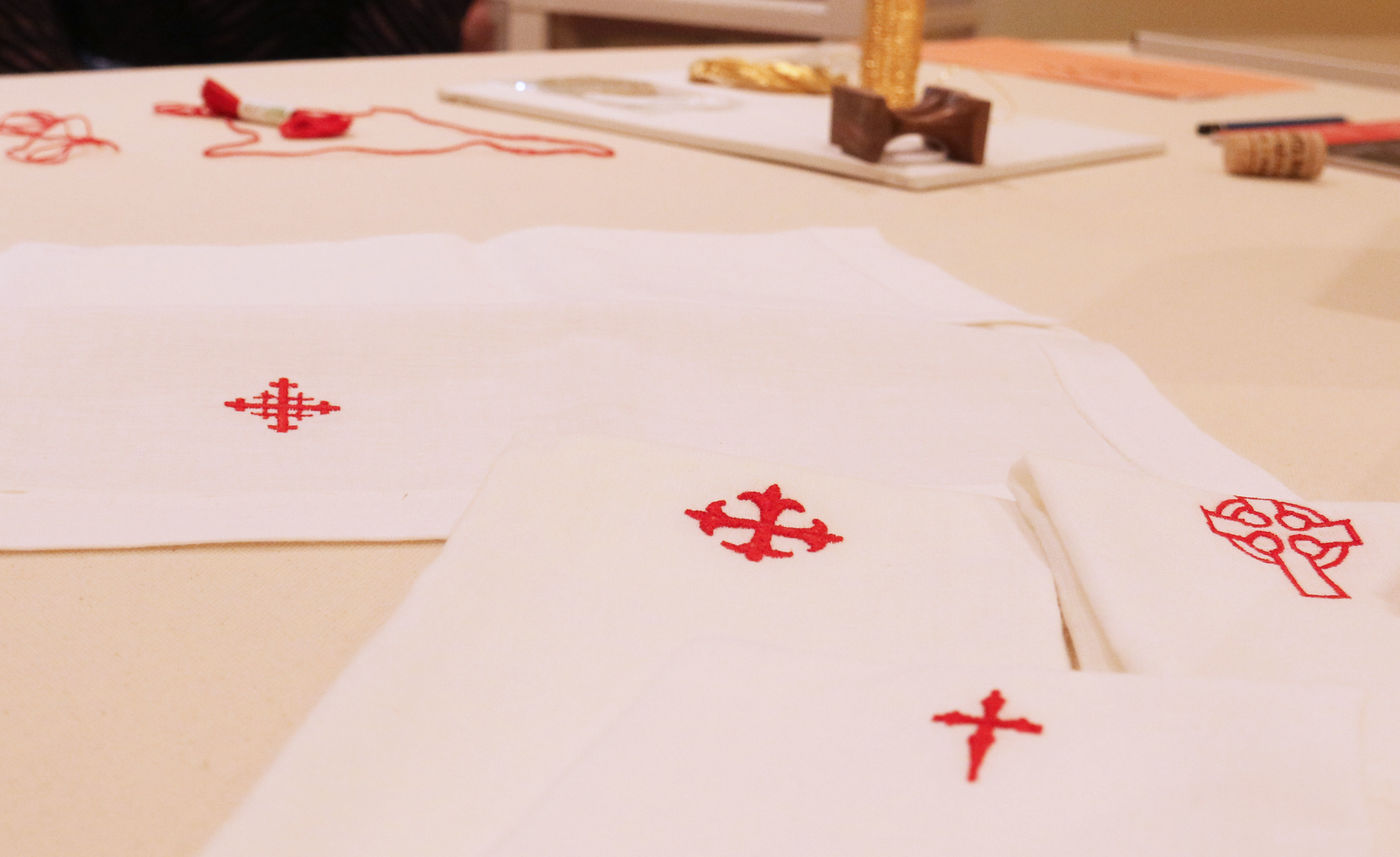

Ilona Payne sews a religious symbol onto a piece of golden silk in her home studio in Langley. (Photos by Agnieszka Krawczynski / The B.C. Catholic)

This is the sixth article in a series on sacred art.

LANGLEY—Classical music plays as a seamstress carefully pulls red embroidery thread through gold-coloured silk in the basement of her home.

“It’s for Jesus, so you sew it by hand,” said Ilona Payne, a member of the Epiphany Sacred Arts Guild. Sacred art is more often associated with iconography, stained glass, and sculptures than with embroidered vestments or little white linens, but for Payne her craft is just as sacred.

Journey to the altar

“There is a meditative rhythm to it,” Payne said. “I think of the quote from the St. Therese, the Little Flower, that even ‘to pick up a pin can save a soul.’ It’s almost as if each stitch can be a prayer. Each time I take a stitch through the linen or run an embroidery thread through, if I am sufficiently focused and I’m giving that gift to God, that is the Little Way.”

Payne works with silks, fine linen, and 24-carat gold leaf thread as she creates hand sewn religious masterpieces. In the last five years, Payne has sewn five vestments, seven altar cloths, a dozen stoles, and hundreds of linens for churches in the Fraser Valley.

The work is time-consuming. There are 15 steps behind the making of a small altar linen, such as a purificator or a corporal. Payne orders raw fabric, preferably pure Irish linen, and takes it through several cycles of washing and drying to shrink it. She then lays out the large squares of material, irons them, and measures them. She marks out 21-inch squares for 18-inch corporals with a hem, shunning a pen for the more traditional method of pulling out a single thread to indicate where to use her scissors.

After the pieces are measured and cut out, she begins the careful process of hand sewing with tiny stitches. Over the years, she’s become quite quick with a needle. Still, it takes about a full day to do one small purificator.

“It takes about a day to make one small linen. Are you going to charge $100 for one small linen? Of course not. So you just do it,” said Payne.

She only bills for materials. “It’s for Jesus. It’s for love. You don’t do it for anything else, because it’s for the altar. It’s the sacrifice of the Mass.”

She has crafted a gold and red chasuble for Deacon Alan Cavin at St. James Parish as well as ornate altar frontals for Sts. Joachim and Ann and St. Joseph’s Parish in Langley. Unlike other artists, her finished products never carry her name, and she enjoys the anonymity.

Learning to sew

Payne has been fascinated with sewing and embroidery since she was introduced to it in Grade 6 in a Catholic school in the north of England.

“The teachers taught us how to do basic embroidery stitches and they gave us all little bits to work on. Then they put it together into this astonishing collage. We could look at it and it was beautiful, and we made it.”

Since those first lessons, Payne became intrigued by the possibilities posed by a needle and thread. She even considered going to England’s famous Royal School of Needlework.

Fast forward a few decades. Payne married, had some children, and settled into a home in Langley, but never let go of her love of sewing. She used her talent around the house, sewing napkins or curtains with no formal training.

Then, five years ago, she got into ecclesiastical sewing by accident. In casual conversation, an assistant pastor mentioned to her that the parish didn’t have a humeral veil, the fabric a priest uses when holding the monstrance.

“I had never really considered the needs of vesture and linens,” said Payne. She told the priest to buy one and was shocked to hear the price.

“I was horrified! A roof needs to be fixed, there’s a hungry family, and it costs how much? So I said ‘okay, I can make that.’ It really is the simplest of vestments.”

After she completed the veil, she couldn’t stop. “I like the challenge. When you do something that’s a skilled craft and that’s artistic, there is an intellectual component and you’re doing something with your hands, and I like that,” she said. “There is something very satisfying, to my soul anyway, that there’s something tangible.”

Not like other sacred arts

There is another way Payne’s craft differs from iconography, stained glass, or sculpting. It can be far less expensive and more accessible to the average pewsitter.

“It can be done very inexpensively and you can make quite beautiful things. The further you go with it, it can go from being a household craft to being fine art,” said Payne.

“This is something where someone with a good heart and willingness could just practise and practise and could become quite competent. A determined beginner could become sufficiently competent to be able to make linens for their parish. It would be a beautiful thing to do.”

Payne dreams of teaching average Catholics how to sew linens for their churches so their pastors don’t have to buy them.

“I think it would be nice. Why, in our parishes, are we spending money on linens? Is it not possible that in each parish that there can be men and women of humble heart who are prayerful and happy to learn some skills? If you make one purificator a year, that’s one purificator the church has that they didn’t have to buy,” she said.

“If you make a corporal, and our Lord’s body rests upon that? Can you imagine? And you made that? It’s a beautiful way to touch the altar.”

Payne draws inspiration from the Shroud of Turin, an ancient linen believed to be Jesus’ burial cloth. An image of it is displayed in the TV room she converted to her home studio.

“It’s an inspiration to me. It’s a very special linen; I believe it’s authentic.”

Read more about local sacred artists from The B.C. Catholic.