Catholic Vancouver September 27, 2017

Monk, 93, puts finishing touches on sculpture of Christ's burial

By Agnieszka Ruck

MISSION—Ninety-three-year-old hands are carefully filling in the imperfections of a bas-relief of the Burial of Christ, soon to be the newest art piece at Westminster Abbey in Mission, B.C.

Ora et Labora

Father Dunstan Massey, OSB, spends about four hours a day in a barn downhill from the stunning abbey church working on his latest creation.

“The work is a prayer,” he told The B.C. Catholic inside his studio filled with drawings, plaster molds, and buckets of materials. “Ora et Labora. That’s what the Rule talks about: prayer and work. The two go together.”

Father

Massey says it’s a unique privilege for a single artist to craft all the artwork

in one church. He has created 22 concrete bas-reliefs for the Abbey, including 20 for the church, since 1982.

“An artist doesn’t very often get a chance to do the whole ornamentation of a church. That’s a rare thing. It’s a privilege to be able to do that.”

Father Massey has filled Westminster Abbey with depictions of holy people from Abraham to the Apostles. His works include a kneeling Angel Gabriel, the founder of the Benedictine order St. Benedict, and even a hardworking St. Peter with a miraculous catch of fish.

The work is a prayer. 'Ora et Labora.' That’s what the Rule talks about: prayer and work. The two go together.

Each of his bas-reliefs hang on the concrete pillars of the church, looking almost as if they were built right into the wall. But after creating 22 concrete statues of saints, angels, and Popes, Father Massey felt something was missing: a focus on Christ.

Prayer

So, the

Benedictine monk spent seven years crafting the crucifix that hangs above the

altar. It was cast in bronze, plated with silver, and hung in 2014. After that

intense project, with the help of some young novices, he started his 23rd

concrete statue: Joseph of Arimathea carrying Christ to the tomb.

“I wanted to bring in two more aspects of Christ’s mission: his burial and his Resurrection.”

The statue is destined for the church’s east end. Father Massey already has plans to create a statue of the Resurrection to appear near it. “From the nave, you will see Christ on the cross, and you’ll see the death and resurrection. It gives a Christological meaning of why all the saints are there.”

The cheerful monk said in his younger years, it took about three months to create a concrete relief. His latest work has taken about two years. “It’s very easy to make a drawing. It’s very hard to produce a sculpture.”

Work

For the burial scene, as with every sculpture, Father Massey begins by drawing out his designs and creating a life-size clay model. He then covers it in plaster of Paris, making a negative mould.

In time, and with the help of novices, Father Massey removes the clay and replaces it with cement and steel reinforcements. The concrete is left to cure for a few weeks, then the monks remove the plaster and touch up the statue.

Father Massey said in the process, the statue has deviated slightly from his original drawings – for the better. Mary and John have gone from mere observers to an essential part of the scene.

“Mary managed to stand for three hours under the cross on which her son was dying. It’s my private idea that, after an ordeal like that, she probably would be suffering a considerable effect of shock,” said Father Massey.

“So I have portrayed her: her eyes are not focused, her hand is reaching out towards Jesus but it’s limp and her posture is beginning to lose its balance. John, appointed by Jesus at the crucifixion to be her son, puts his hand on her arm to steady her.”

Meanwhile, Father Massey depicts Christ as deceased but hiding the “great big secret” of Easter on his peaceful face as Joseph of Arimathea and a servant carry his body to the borrowed tomb.

Community

Benedictine

Brother Joseph Bruneau said the incredible artwork inside the church

shows the strength of the whole

Abbey community.

“As the young ones are helping Father Dunstan now, we’re hearing stories from the older monks who say, ‘we remember doing St. Benedict with him.’ There are all these crews of people who have worked together. Everyone has done something. The art is here because there is a community.”

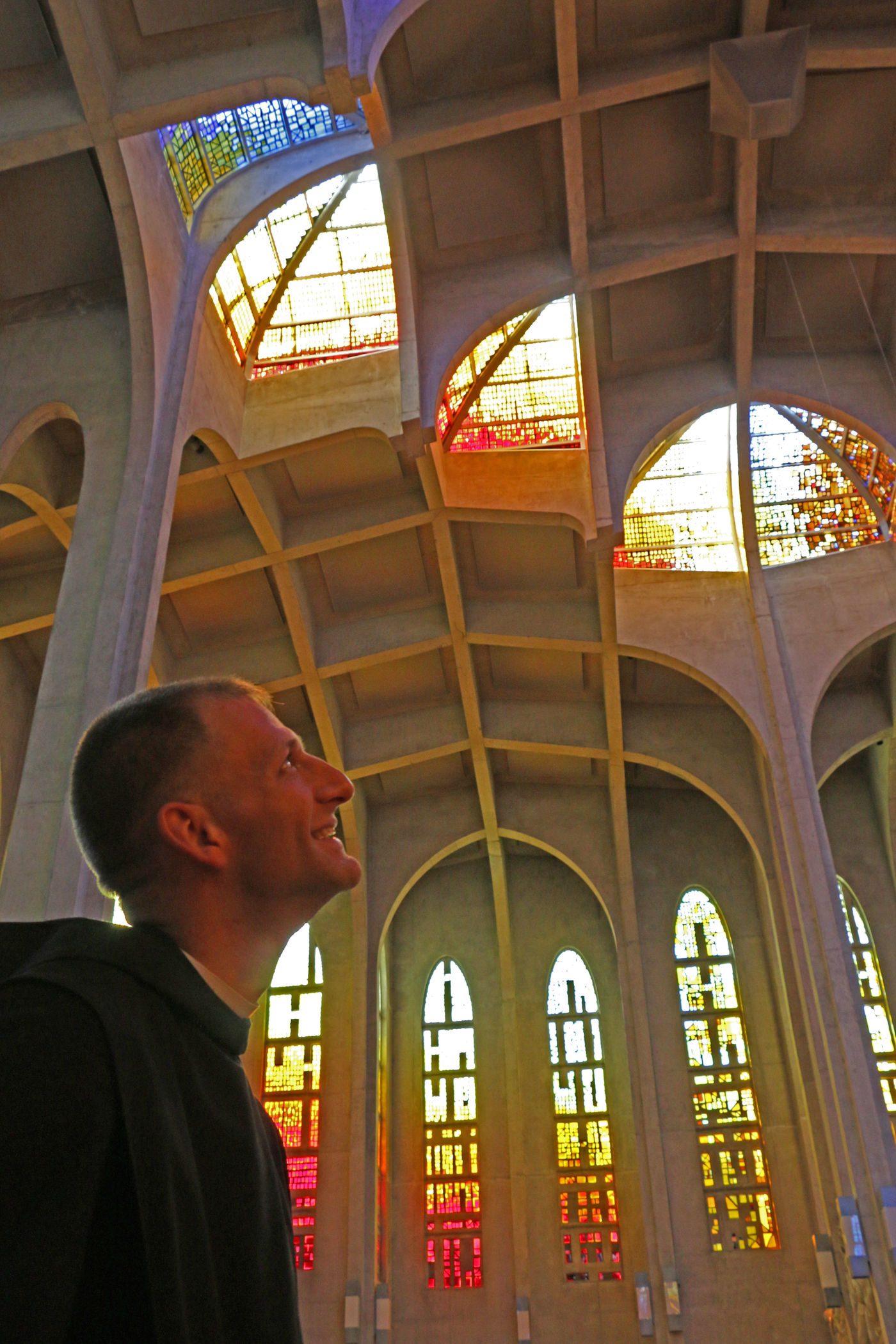

Brother Bruneau was recently tasked with replacing the stained-glass domes on the Abbey church roof. They were originally installed in 1981, in time for the dedication of the church by Cardinal Basil Hume, OSB, in 1982.

But within two years, the colourful domes were leaking and an exterior dome was installed to keep the church dry. Then, by 2012 the thick pieces of glass, fastened 60 feet above the altar with epoxy, began falling out.

“They came to me and said: ‘I want you to take that out as fast as you can,’” said Brother Bruneau. Enlisting the help and imagination of brother monks, he chipped away at the domes and cleared out the stained glass within two weeks.

For the next few years, the Benedictines celebrated Mass under a plexiglass dome while they tried to come up with a safer way to install stained-glass roofing. Armed with new ideas and plans, they began installing the glass (including some pieces of the original roof) in 2015, and the final pieces were in by Easter 2017.

“Pretty much everyone who has entered the community since this has been a project, has worked on this, sometimes for hours,” said Brother Bruneau.

“Many members of the community who didn’t work on it, really worked on it by filling in where we should have been. That’s the thing that’s little appreciated about the art: it’s only here because there’s a community here.”

Now, the brightly coloured stained glass throws shades of red, yellow, and blue on the floor, walls, and Father Massey’s cement saints.

At 93 years old, Father Massey is not sure how much longer he’ll be able to craft statues for the Abbey, but he already has drawings ready for statues to come after the Burial and Resurrection.

“Under the dome, we want to put the four evangelists, two by two, and the major prophets of the Old Testament. That’s eight more. I won’t be around to do it, but I’ve designed them,” he said, shuffling around his studio in a Benedictine habit dusted in plaster.

“Ora et Labora. Prayer and work.”