To contribute to a dialogue of healing and understanding following the Kamloops Indian Residential School announcement, The B.C. Catholic is sharing stories of individuals who have been working toward truth and reconciliation. We’ll publish first-person accounts as well as interviews over the coming weeks.

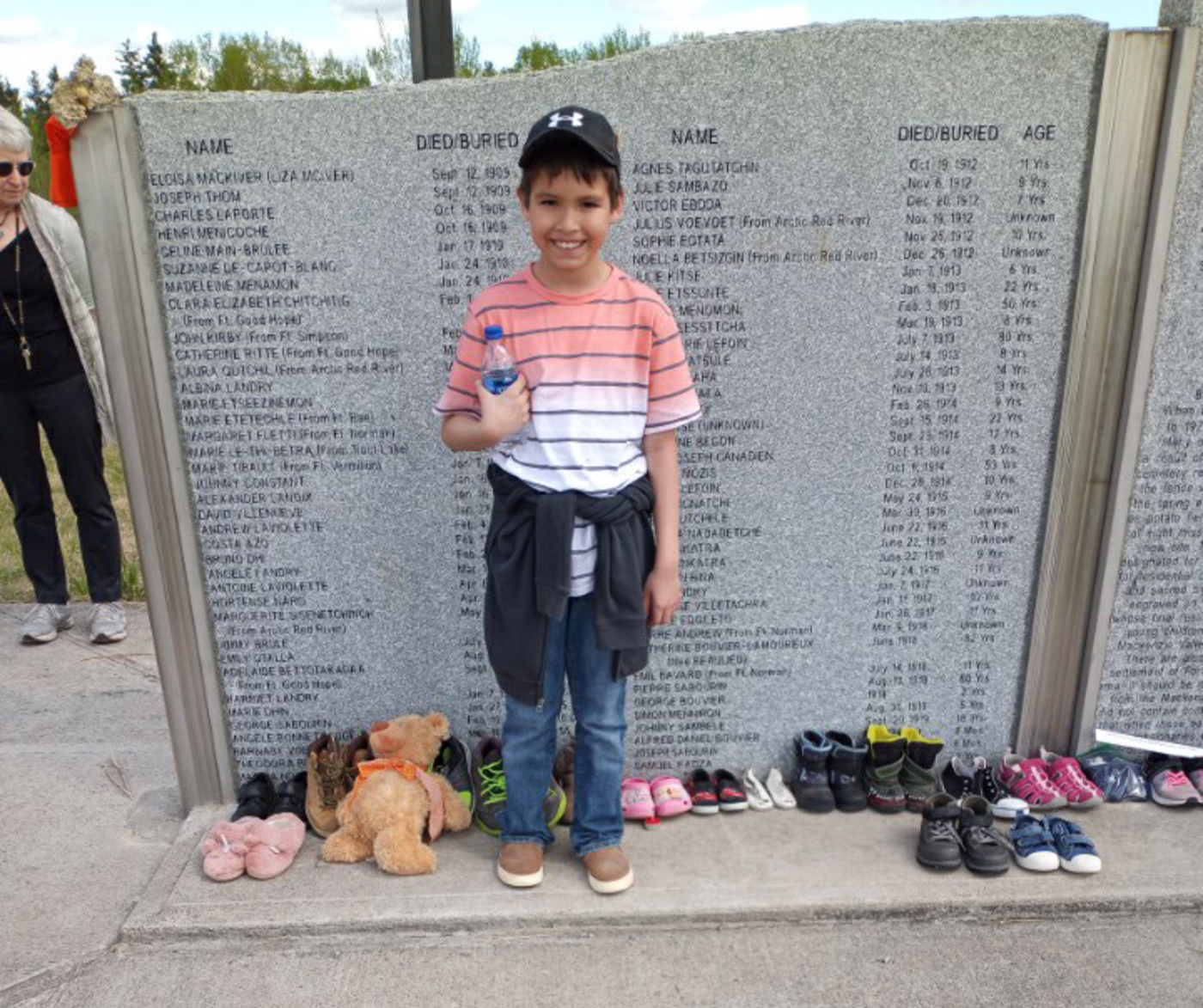

Shoes and stuffed toys surrounded a memorial on the grounds of Sacred Heart Mission School Cemetery in Fort Providence, NWT, this week to honour lives lost at residential schools.

The memorial is a large cement block with the names of some 300 children and adults buried on the Fort Providence site. With no individual grave markers in view, the structure is the only clear sign of the significance of the place.

Several dozen people gathered at the memorial as the group remembered in particular the 215 children whose remains were reported discovered in an unmarked site more than 1,600 kilometres away in Kamloops.

Among the participants was residential school survivor and Dene elder Monique Sabourin.

“It was really sad for me,” said Sabourin. “I think what hurt me the most was that kids are so innocent. We were brought up with loving parents, but to be dragged away? I want to know, how did those kids, 215, how did they die? Why are they buried there?”

“How did they manage to take the babies away from their parents?”

In the 1960s, Labourin attended LaPointe Hall, a residential school where she was sexually abused by a priest and also faced physical abuse. The experience led to alcohol addiction, a rejection of her Catholic faith, and years of pain. She tells her story and describes her journey toward healing in the 2017 documentary In the Spirit of Reconciliation by local filmmaker and priest Father Larry Lynn.

“How do you forgive? That was the question I asked myself,” she said in the documentary. “How do you forgive something that happened to you as a child, when everything was taken away from you?”

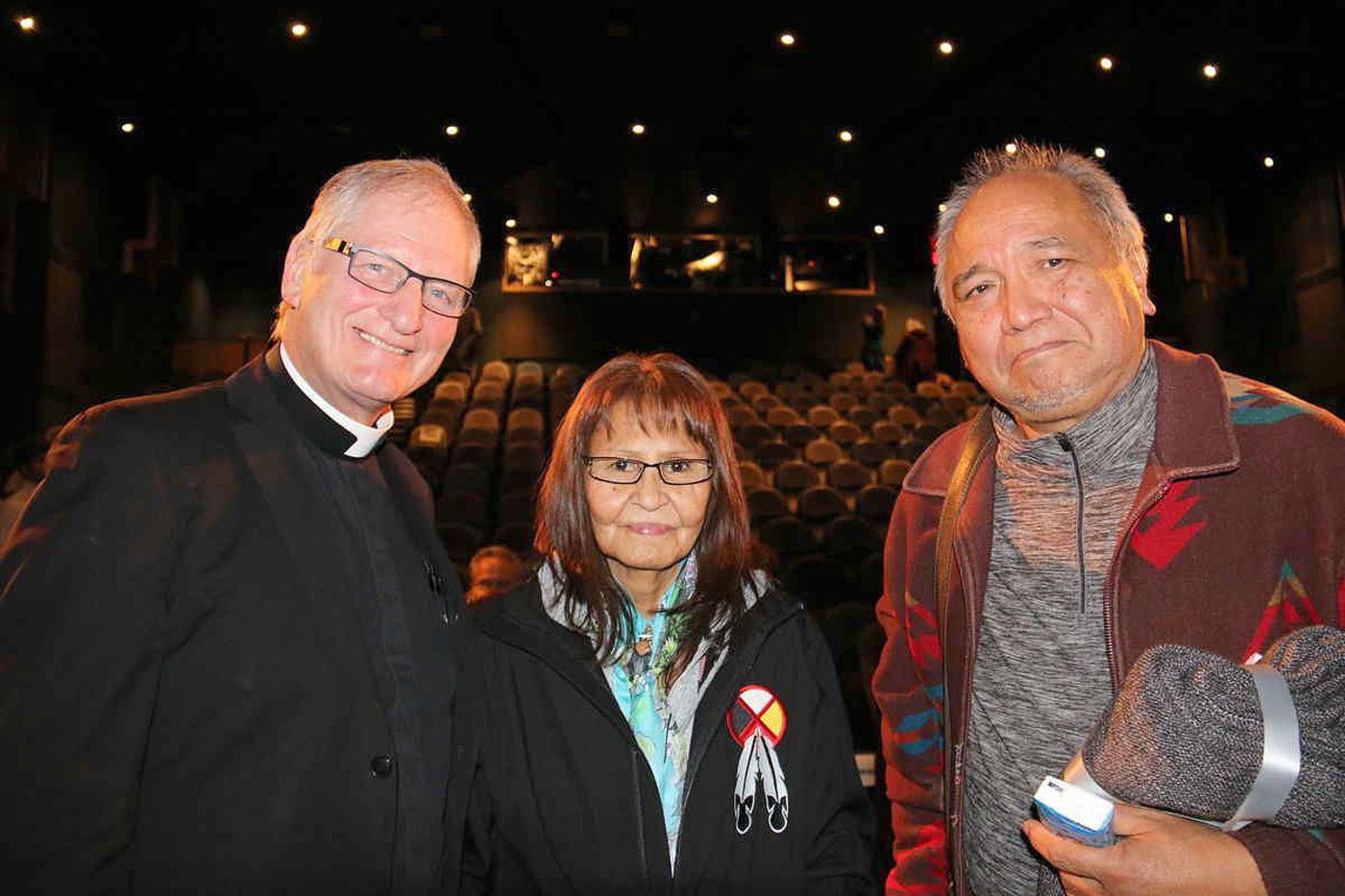

Monique Sabourin with Father Larry Lynn and former Lieutenant Governor of B.C. Steven Point at the world premiere of Father Lynn’s documentary In the Spirit of Reconciliation in 2017. (BCC file photo)

Today, she says that healing journey is still an ongoing process.

“We still deal with this stuff every day,” she said. “I thought it was over, but it’s never over, as long as you’re there.”

For Sabourin, her key to wholeness has been forgiveness.

“Its hard to forgive what happened to you, but you have to forgive to go on. It is what it is. You cannot do nothing with it. It happened. You cannot go back and change it. You just have to forgive and walk with your head up and say, ‘Jesus loves me,’” said Sabourin, who has returned to her Catholic faith and works to help others in Fort Providence overcome addiction.

“I’ve been hurt so many times, I could say ‘I will not forgive.’ But that’s not the answer to anything.”

Since she heard about the discovery of the grave site in Kamloops, she has been lighting candles at home daily in honour of the 215.

“Everybody’s talking about apologies and everything that has to do with residential schools and the 215 kids that they found, but nobody is doing anything for those little souls to go to Jesus,” she said.

At the memorial, “when I heard the sound of the drum, I closed my eyes and in my mind, in my imagination, I saw 215 little souls going up to heaven. It was the image I had. I really pray that they are in heaven.”

Some of her most challenging moments are when people disbelieve that abuses were perpetrated on students at residential schools – comments of the sort she has seen on social media in recent weeks.

“It really, really affected me. I was so emotional, I had to go out and pray.”

In the wake of the Kamloops discovery, she hopes to see apologies from the government, the RCMP, and Catholic leaders.

She said those who insist on an apology from the “Catholic Church” misunderstand the meaning of Church.

“We are the Church. How do we ask for an apology from the Church if we are the Church?” she said, counting herself as part of that body. “We are asking for an apology from church leaders, not from the people.”

She also hopes to see funding for survivors.

“I’m hoping that the government can repay everybody that went to residential school so they can go on their own healing journey. I’m still on my healing journey. You want to do it on your own, but there is no money for it. The government should pay every individual that was in residential school.”

Meanwhile, she holds her head high and teaches her grandchildren about residential schools and what it means to forgive.

“We are loved. We can go on. We can start over with forgiveness, because God loves every one of us. He lay his life down to share, you know. He loves us no matter what.”

One of her grandsons attended the ceremony in Fort Providence and she snapped his photo in front of the cemetery memorial.

“I told my grandson, ‘I’m taking this picture of you because those grandchildren are not home, but we are so blessed with you,’” she said.

“Forgiveness is a key to a door. If you open that door and open it wide: Wow, look at the beautiful world. You don’t have to live behind closed doors.”