Catholic Vancouver November 25, 2021

Secret talks, dismissed experts: documents show Fraser Health’s grim push of MAiD on hospices

By Terry O'Neill

Records obtained by The B.C. Catholic through a freedom of information request reveal the Fraser Health Authority decided to impose euthanasia in hospices after holding secret meetings contrary to policy and despite the recommendations of its own palliative care experts.

Heavily redacted records of in-camera Fraser Health meetings show its directors rejected advice from Dr. Neil Hilliard, medical director of its palliative care program, and Dr. Steve Mitchinson of the Complex Palliative Care Unit of Abbotsford Regional Hospital when the health authority decided in 2017 to force the region’s hospices to allow doctor-assisted killings on site.

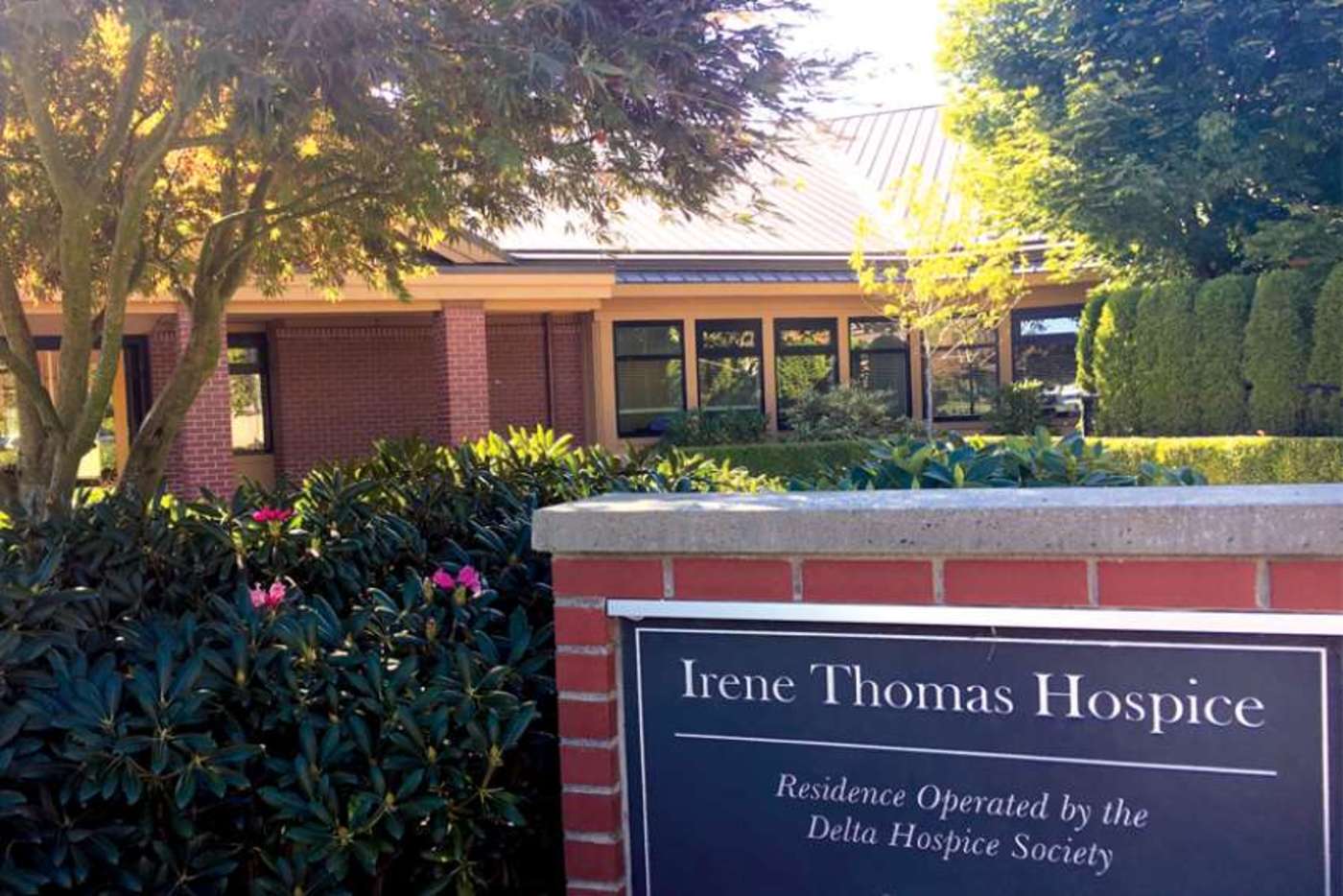

The decision to impose so-called Medical Assistance in Dying on hospices led not only to the resignation of Hilliard as head of Fraser Health’s palliative care program, but also to a bitter, ongoing struggle with the Delta Hospice Association, which refused to follow the health authority’s edict.

Release of the secret papers follows a year-and-a-half-long fight by The B.C. Catholic to obtain documents relating to the development and implementation of Fraser Health’s assisted suicide policies after receiving complaints that health workers were pressuring vulnerable patients about the availability of “medical assistance in dying.”

Fraser Health policy documents released earlier this year in response to the newspaper’s FOI request revealed that a patient’s decision to access assisted suicide in the health authority’s facilities is supposed to be an “entirely patient-driven” process.

The newly released documents are so heavily redacted that it’s not possible to determine whether they contain information about imposing euthanasia on patients or facilities. In a follow-up request, The B.C. Catholic is seeking more transparency about the documents, which show numerous meetings of the board and its committees in which “physician assisted suicide” was discussed, although details of those discussions are censored.

Fraser Health’s own policy says board meetings, but not committee meetings, are to be open to the public with the exception of discussions of matters such as legal advice, law enforcement, or business interests of a third party.

The newly released documents show that on Aug 16, 2016, the board’s Quality Performance Committee received a detailed report from Hilliard and Mitchinson in which they argued that physician-assisted death is incompatible with hospice care.

“There should be no fear by patients or family caregivers that physicians or staff have any intention other than to provide a palliative approach to care until they die, or that we will abandon them,” the doctors’ report said. The quality committee simply referred the issue to a board steering committee on MAiD.

Records of a Sept 15, 2016, meeting of that committee show “potential solutions” were discussed, and a motion passed, but the details of those items were censored under confidentiality restrictions.

The issue came to a head at the June 13, 2017, meeting of the board of directors, during which they voted unanimously (with one abstention) in favour of a motion declaring that, “in order to minimize the negative impact of unnecessary patient transfers,” the board would support “the administration of MAiD procedures in the location of the patient’s request/preference.” In other words, hospices would be required to allow assisted suicide to take place rather than facilitate the patient’s transfer to a more suitable institution.

The motion also stated that implementation of the MAiD policy “will require full commitment from the Palliative Care Program Leadership, to support both palliative physicians and staff in person-centred care, while still respecting the ability for conscientious objectors to abstain from participation in the procedure.”

Hilliard resigned his post soon after.

In a statement to The B.C. Catholic, Hilliard said it was ironic and unfair that, while freedom of conscience was allowed for health-care providers, there was “no freedom for conscience for health-care leaders” who would be forced to allow euthanasia in their facilities.

Hilliard also charged that “valuable palliative care resources were used in the provision of MAiD when there was still a large percentage of individuals without timely access to palliative care services.”

The previously undisclosed documents are significant, said Alex Schadenberg of the Euthanasia Prevention Coalition and confirm his view that Fraser Health is the most aggressive and influential health authority in Canada in promoting euthanasia.

Fraser Health’s unrelenting and, ultimately, successful drive to impose assisted suicide in every corner of its operations has had destructive effects throughout Canada, Schadenberg told The B.C. Catholic. He said the authority’s policies have been adopted throughout B.C., and, while no other province has forced hospices to provide assisted suicide, hospices in Quebec and Ontario are being pressured to do so.

Schadenberg said it is important to recognize the example set by Hilliard in his principled opposition to the unchecked spread of MAiD. “I think he is a hero,” he said.

He also applauded the “intestinal fortitude” shown by the Delta Hospice Society, which resisted Fraser Health’s directive until B.C. Health Minister Adrian Dix forced the hospice to close on March 29. Two weeks later, Fraser Health re-opened the facility as a government-run, euthanasia-friendly institution.

Although its two buildings had been built by the society with $8.5 million in private funds, they were situated on government property and received operational funding from Fraser Health.

“The FHA was so enthusiastic about euthanasia that they had their own little MAiD policy before even the province of British Columbia had one, as far as we know,” society president Angelina Ireland said in an interview. “The law is that there shall be access [to MAiD], and they interpreted this to mean that there must be access at every single bed in British Columbia. That’s not what the law is.”

Ireland said she did not want to comment on whether the society is trying to regain control of the hospice. Rather, she said, the society will focus on protecting “authentic palliative care.”

“As such, we want to build a new hospice, another hospice,” she said. “This one will be completely private – no government, no Fraser Health funding, nothing. It will be a private venture that will be a sanctuary for the dying, so that patients will be protected from MAiD.”

The society, which now has “well in excess of 10,000 members” from across Canada, will hold a virtual AGM in the near future to determine its next move, Ireland said. “Our fight has just begun. We don’t need the government. In fact, they’re just an impediment. We have a vision that far exceeds their scope.”

How The B.C. Catholic obtained the secret records

The Fraser Health Authority documents are records of several “in-camera,” or closed-door meetings of its board of directors and two of the board’s committees. The papers were made public as a result of a freedom of information request by The B.C. Catholic filed in March 2020.

In an initial response to that request in February of this year, Fraser Health released a limited number of records dealing with the development of its “medical assistance in dying” policies. Those documents showed that the health authority’s official policy called for administration of MAiD to be a patient-led process.

However, The B.C. Catholic reported that this appeared to be in sharp contrast to anecdotal reports that sick and elderly patients were being pestered about accepting doctor-assisted death.

At the same time, Fraser Health’s freedom-of-information office withheld all MAiD-related board-of-directors’ reports, agendas, and minutes on the grounds the meetings were closed to the public.

On March 30, 2021, The B.C. Catholic filed an appeal to B.C.’s Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner, seeking the release of the board documents.

In July, an OIPC investigator said in a letter that a mediation process would take place to settle the issue.

On Nov. 1, before such a process was initiated, the FHA released 131 pages of heavily censored documents. Neither the FHA nor the OIPC explained the release at the time but, in response to questions from The B.C. Catholic, Curtis Harling, Fraser Health’s senior communications consultant, emailed an explanation on Nov. 17.

Harling said the OPIC followed standard practice when it asked Fraser Health, prior to any mediation meeting taking place, to re-consider its redactions given the time that has elapsed since the records were first processed and in light of any relevant OIPC orders.

“Based on this, Fraser Health concluded that it could release some of the records it had previously redacted,” Harling said. “Fraser Health always values the guidance provided by the OIPC and uses such guidance to improve its FOI processes going forward.”

Nevertheless, much of the 131-page document remains blacked out, so, acting on The B.C. Catholic’s request, the OIPC will now take the matter to a formal inquiry where an adjudicator will decide, with a binding order, how much of the redacted material can be made public. Shannon Hodge, Senior Investigator with the OIPC, said the process may take 18 months.

Broken trust and shattered integrity: an interview with Dr. Neil Hilliard:

Dr. Neil Hilliard was the respected head of palliative care for the Fraser Health Authority region in 2017 when a board-mandated policy, calling for FHA leadership to support the provision of doctor-assisted death in hospices, forced him to resign on a matter of principle.

Dr. Hilliard is now 69 and retired from medicine. At the invitation of The B.C. Catholic, he offered written comments on the now-public FHA board documents surrounding implementation of its Medical Assistance in Dying policies. Here is an edited version of his response:

My question after reading the Fraser Health Board minutes is why was this all discussed in camera and why is much of the information provided to you redacted? Was this to prevent opposition to the agenda to provide MAiD “wherever the patient resided” under the guise of patient-centred care? Was the palliative-care program now considered the enemy because of its philosophy to help people with life-limiting illness live well until they die a natural death?

For the 95 per cent or more of individuals who do not choose MAiD at the end of life, do in-camera sessions and redacted minutes inspire trust in the health authority? Do bullying tactics against hospices, which wished to stay true to their founding principles of palliative care, inspire trust?

If the palliative-care leadership does not have freedom of conscience to provide palliative care, free from the provision of MAiD, or resign, how is the rest of the palliative-care team to preserve its own integrity?

One can see from the minutes that, from the very first, there was a bias to MAiD. The truth is that the provision of MAiD is the antithesis of palliative care and should not be merged but kept separate from palliative care. Deception is even present in the term “Medical Assistance in Dying,” since this is what palliative care has been all about from the beginning, but not by intentionally ending a patient’s life.

To regain trust in the provision of palliative care, “hospice sanctuary” will be necessary, funded privately and not subject to government- or health-authority-forced direction to provide MAiD.