Catholic Vancouver February 25, 2021

Patients being offered euthanasia contrary to Fraser Health policy, B.C. Catholic investigation finds

By Terry O'Neill

First of three stories.

See also: Chilliwack death shows euthanasia system subject to abuse: couple

An investigation by The B.C. Catholic has found that patients in the Fraser Health Authority have been offered death by euthanasia without requesting it, contrary to the health authority’s safeguard policy of requiring patients to raise the issue of assisted suicide.

Patients, concerned citizens, and medical personnel have told The B.C. Catholic that medical personnel in Fraser Health and elsewhere often suggest “Medical Assistance in Dying” (MAiD) before patients ask about it, and do so even before outlining details about palliative care.

With respect to Fraser Health, at least, such a proactive, promotional approach to assisted suicide appears to be a breach of its own policy, which clearly states that MAiD is supposed to be an “entirely patient-driven” process.

That declaration is found among 115 pages of documents obtained by The B.C. Catholic in answer to a Freedom-of-Information request it filed in March 2020. The request sought information about the development and implementation of Fraser Health’s MAiD policy, including details about any compliments and complaints the authority, which serves 1.8 million people from Burnaby to Boston Bar, might have received.

The application was made in response to information received from a Coquitlam-area woman who said that, while she had been struggling to recover from a severe illness in a hospital administered by the FHA, she was repeatedly told by staff that she could always access assisted suicide. She told The B.C. Catholic she felt pestered, pressured, and discouraged at a time when she needed all her strength to recover.

Fraser Health’s communications office did not respond to a request for information about the apparent breach of its “patient-driven” policy.

Even staff’s mere introduction of the possibility of assisted suicide puts undue pressure on patients when they are the most vulnerable, says Dr. Williard Johnston of Vancouver, a family physician who is also the head of the B.C. Branch of the Euthanasia Prevention Coalition.

He said in an interview that he has learned that Fraser Health “quite aggressively started pushing euthanasia in every corner” of its operations, from hospitals to hospices, soon after the practice became legal in June 2016.

“It’s not rational provision of medical services,” Johnston said. “It’s not provision of services that is being geared to the population. It’s being geared to the ideology” of “radical autonomy.”

Anti-euthanasia activists say this is worrisome because, with Canada’s already permissive MAiD law set to become even more liberalized under Bill C-7, assisted suicide abuses may grow even worse.

To draw attention to such abuses, the Ontario-based Compassionate Community Care organization placed newspaper advertisements earlier this month asking Canadians to share stories of malpractice associated with euthanasia. It cited several already known cases, including those of:

- Roger Foley, an Ontario man suffering from a neurological disease who in 2018 provided reporters with audio recordings that he said proves hospital staff promoted medically assisted death even while they would not provide him with assisted home-care; and

- Alan Nichols, a mentally ill man who was euthanized in Chilliwack General Hospital in 2019 even though his family said he was not critically ill. (See related story.)

Similarly, LifeSiteNews reported in mid-February that Dr. Corrina Iampen, a GP from Kelowna who had become paralyzed in an accident and is not opposed in principle to assisted suicide, was nevertheless disturbed when, out of the blue, a doctor introduced the possibility of her choosing to have herself euthanized. The “timing was really poor” and “inappropriate,” Iampen was quoted as saying.

As well, CBC reported in 2017 that Sheila Elson, from Newfoundland Labrador, was upset when a doctor said, without prompting, that assisted suicide was an option for Elson’s daughter, Candice, who suffers from spina bifida and cerebral palsy. “I was shocked and said, ‘well, I’m not really interested,’” Sharon Elson told CBC, “and he told me I was being selfish.”

In B.C., Angelina Ireland, president of the Delta Hospice Society (which Fraser Health has stripped of its ability to run the Delta hospice because of the society’s opposition to euthanasia), said in an interview that the authority “has been the most aggressive as a proponent of MAiD, more than any other health authority in British Columbia.”

“You’re damn right, there is pressure,” Ireland said. “I’m sure there’s many, many stories out there about this happening to people, because it’s now institutional.”

Nancy Macey, founder of the Delta Hospice and its former executive director, agreed with Ireland, but was not able to provide details of instances. She said, however, that it is vital for government to establish “safe spaces” for the very sick and elderly in which assisted suicide is not mentioned or practised. Otherwise, “they cannot stop physicians from putting that pressure” on patients.

But that is exactly what is happening, says a registered nurse who works at a hospice in the Fraser Health region. The nurse, who asked that her identity and exact place of employment be withheld for fear of repercussions at work, said in an interview that doctors assessing incoming patients inform them of the possibility of assisted suicide but, as a matter of course, do not describe alternatives, such as palliative sedation.

Moreover, she said RNs are not allowed to talk tell patients about palliative sedation. “When we do it, doctors get upset,” she said. “Previously, we were able to do it. Now they cut us out. It is so very upsetting. Patients need to be educated.”

None of this comes as a surprise to Alex Schadenberg, executive director of the Euthanasia Prevention Coalition. “I am hearing stories like this from all across Canada,” Schadenberg said in an interview.

He said health authorities initially may have intended to make euthanasia “completely patient driven,” but euthanasia advocates have successfully pushed the argument that failure to inform patients of their right to MAiD is a breach of their human rights.

If so, that is not reflected in the policy documents provided to The B.C. Catholic in response to its FOI application. Rather, all statements about providing MAiD information assume a patient-initiated discussion.

For example, one document declares, “As Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) is entirely patient driven, it can raise ethical and clinical challenges where family are not aware or aware but not in agreement with the patient’s choice.”

Elsewhere, a document reads, “It is important to recognize that the patient inquiring about medical assistance in dying has chosen you to discuss this topic with because they trust you … Medical assistance in dying is a legal option for care in Canada and people have the right to know/learn/ask about this information.”

Another document on “Standards” and “Expectations” describes how Fraser Health should have “structure and processes in place to: 1.1 Respond to an individual’s request for information about Medical Assistance in Dying.”

Nowhere in the 115 pages is there any listing of expectations, structures, processes, standards, principles, rules, or regulations concerning a physician or other medical personnel’s introducing the subject of assisted suicide without first being asked for information.

With clear evidence that such unwanted communication is happening, anti-euthanasia advocate Dr. Ramona Coelho said physicians should be prohibited from introducing the subject. “It is extremely important that doctors never say to the patient that they could be better off dead,” said the Ontario physician, who has testified against Bill C-7 before House of Commons and Senate committees and is a leader of the MAiD to MAD movement, which has collected the signatures of 1,200 Canadian doctors expressing concerns about the dangers the bill poses to vulnerable Canadians.

“There’s nothing in the medical evidence” to show that death is a better outcome than disease, Dr. Coelho said in an interview. “It is highly unprofessional and very dangerous” to suggest otherwise.

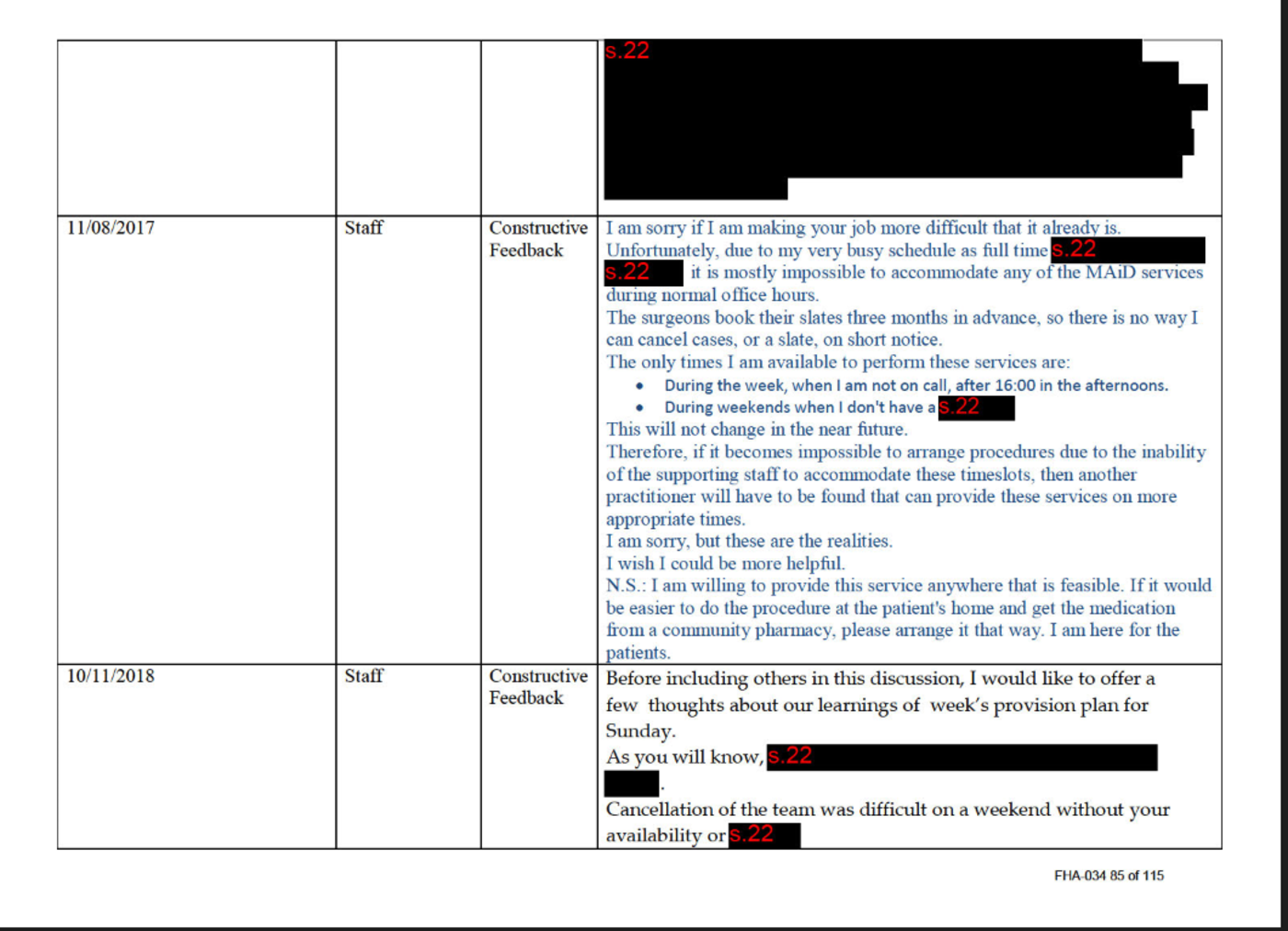

The B.C. Catholic‘s FOI request also sought details of complaints or compliments the health authority had received about its MAiD policies and practices. In response, the authority provided heavily censored documents detailing several compliments and constructive criticisms, but no listing or details of any complaints. (The FHA explained in a letter that it had redacted many portions of the responses because they contained “third party personal information.”)

The only indication of complaints came in a separate document listing raw numbers of MAiD-related comments. It showed one complaint in 2017, none in 2018, seven in 2019, and two in 2020. Compliments and requests for assistance or information totalled two in 2017, six in 2018, four in 2019, and two in 2020.

Fraser Health’s FOI office said it was still collecting information in response to other aspects of the B.C. Catholic’s request, including copies of agendas and minutes of the FHA board of directors’ meetings in which the MAiD policy was discussed and/or acted upon.

To let Terry O’Neill know about a negative or wrongful experience with assisted suicide/MAiD, email him at oneills@telus.