Catholic Vancouver January 13, 2022

Condition critical: The moral imperative to fix Canada’s crisis in health-care capacity

By Terry O'Neill

Throughout the 22-month course of the COVID-19 pandemic, health officials have continually stressed that restrictive measures, ranging from mask mandates and distancing requirements to business closures and congregation limits, have been necessary to prevent the country’s health-care system from being overwhelmed.

Typical of this messaging was B.C. Provincial Health Officer Bonnie Henry’s comments during a televised “town hall meeting” on Jan. 10 in which she at least twice cited this reason as a justification for current restrictions.

Increasingly, however, questions are being raised about why the health-care system is so fragile in the first place, what should be done to make it more robust, and why officials such as Henry and B.C. Health Minister Adrian Dix do not address a health-care-capacity problem that was acute long before the pandemic pounded the world.

With evidence mounting that Canada’s health-care system is failing to serve the country properly, the problem is more than just a political, financial, and health one; it’s a moral one.

The Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops, for example, stated in a 2005 pastoral letter that “health-care justice obliges a society to provide all its citizens with an appropriate level of health care … Good health for all, understood as physical, emotional, spiritual and social well-being, is an essential core value.

“If the legitimate needs of all citizens are not met, the whole fabric of society suffers.”

Henry and Dix might have had the opportunity to address the question during the town-hall meeting if the event moderators had addressed a question submitted by a B.C. Catholic correspondent pointing out that Canada’s hospital-bed-to-population ratio, at 2.52 per 1,000, was the lowest of any G8 nation and just half of the World Health Organization’s suggested ratio of five per 1,000.

“What steps,” the question asked, “are being taken to increase hospital capacity leading to a more robust health-care system?”

The B.C. Catholic has sent inquiries to the B.C. Ministry of Health requesting exact bed-to-population figures for the province, but they’ve gone unanswered. The B.C. Catholic has twice asked the B.C. Liberal Party health critic a similar question and has not received an answer.

Health care is a provincial responsibility, but the federal government has been providing extra funding for the past 40 years. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau reportedly said last week that negotiations to increase health transfers to the province would take place once the pandemic ends. In the meantime, Ottawa has committed to increase transfers by 4.8 per cent, to about $45 billion this coming fiscal year.

Total national health-care funding already accounts for 11 per cent of Canada’s GDP – the seventh highest of the 44 countries measured in 2020- ‘21 by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Yet OECD charts show that Canada ranks just 16th in life expectancy and 23rd in mortality from avoidable causes.

There’s a simple but frustrating reason for this, says Nadeem Esmail, a senior fellow with the Fraser Institute, an economic- and public-policy think tank. He said in an interview that the pandemic has exacerbated an already acute health-care problem in the country.

“The system is not struggling for a lack of financing, it’s struggling from all the things that an already high level of finance should be purchasing,” he said. “And that leads to the question of why we aren’t getting what we’re already paying for.”

The answer, Esmail said, can be found in countries that have universal health-care systems similar to Canada, but more efficient spending and healthy outcomes – countries such as Switzerland, Sweden, the Netherlands, and Germany.

All of them, he said, allow a private alternative to the delivery of hospital and physician services. “When we look at Sweden for example, in the early 1990s, it moved away from a system that was a little more similar to ours, towards a system that had private competition in the delivery of universally accessible services,” Esmail said.

“And it had money following patients to hospitals. What they found is that they could deliver more health care for fewer dollars than they were able to prior to reform. And that’s the sort of reform we need to be thinking of in Canada.”

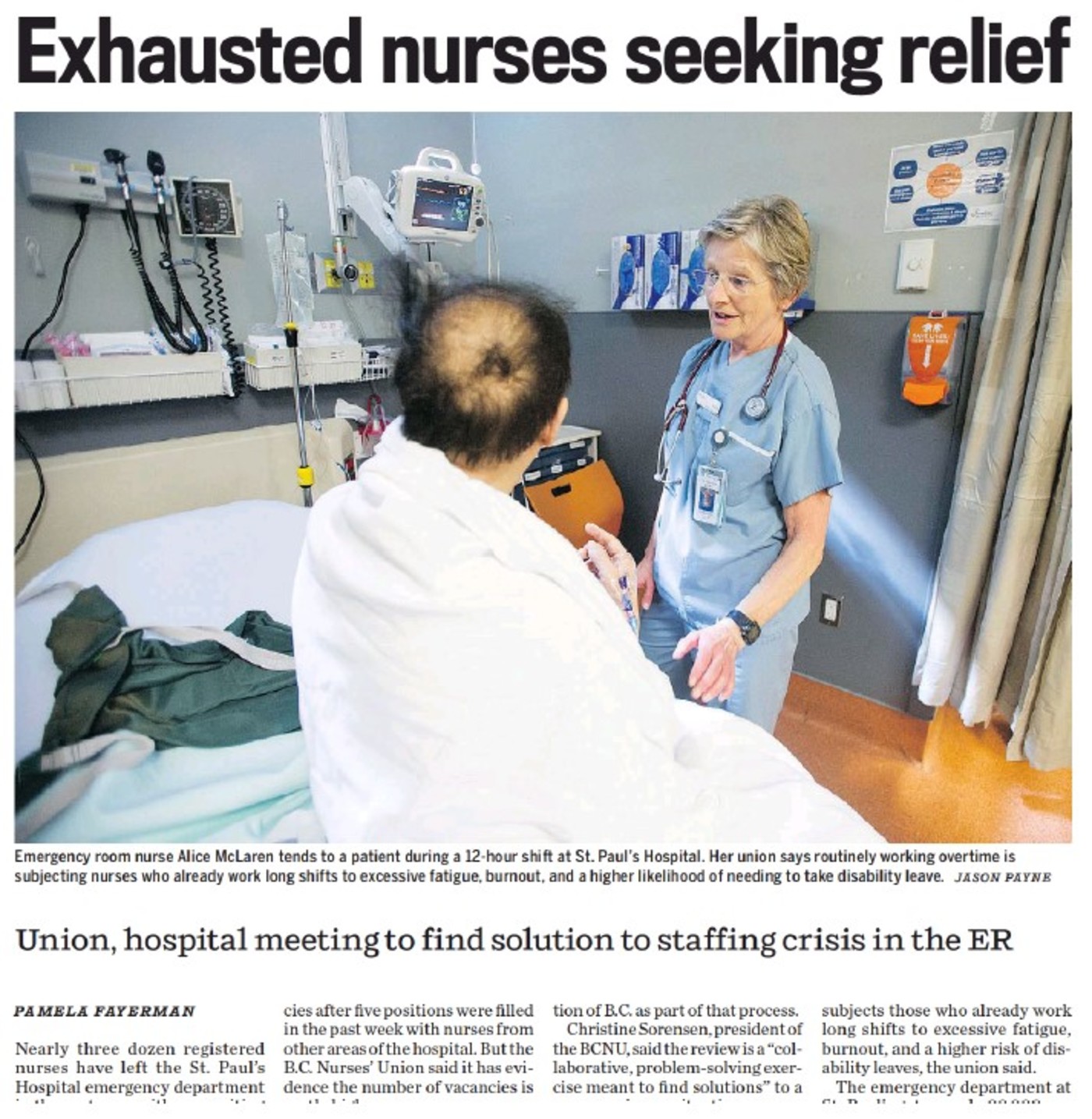

In other words, the solution to the country’s health-care woes cannot be found in simply spending more money. And neither can it be found in pouring more money into health-care infrastructure, said Bob Breen, executive director of the Catholic Health Association of B.C. “You could throw billions of dollars into new infrastructure tomorrow, and it wouldn’t improve anything because we simply don’t have the staff,” Breen said in an interview.

He said B.C.’s health-care system has thousand of unfilled positions for doctors, nurses, and paramedical staff. Moreover, “There’s a waiting list for nursing schools,” Breen noted. “But even if schools are given new funds to accept more students, where are they going to get the staff to teach the students?”

The problem is exacerbated by the fact “we are still using the same models for health care” as we did a generation ago, even though for the first time in our history there are more people over 65 years of age than under 16, and it’s seniors who consume far more health-care resources.

The CCCB’s pastoral letter explains the moral imperative driving this issue. “With this pastoral letter, we wish to make Catholics, and all Christians in general, more aware that the mission of caring for the sick is essential to the life of every Christian and of a just society,” the bishops said.

Indeed, the issue arises “at the intersection of several Catholic social principles,” said Matthew Marquardt, president Toronto-based Catholic Conscience, a Catholic, non-partisan civic and political leadership and engagement organization.

“It's difficult to overstate the importance of health care,” he said in an email interview. “The Church teaches us that the purpose of life is for each of us, being a lost child of God, to find our way back to God, helping each other as best we can along the way. In that light, it's easy to see that in the Church's view the purpose of government is to provide a social, legal, and economic framework that enables us and encourages us to do that.”

Not surprisingly, he said, the Church also recognizes the fundamental importance of health care. “What does that mean for health care in Canada? In Canada, we have entrusted social responsibility for basic health care to our governments,” Marquardt said. “Among the implications of that is that we have a primary responsibility to look after ourselves … But when we need help, we are expected to look to the government for assistance, and government has accepted that responsibility.”

In doing so, government has a responsibility to fulfill its duties in accordance with the moral virtues of wisdom, humility, and prudence, he said.

“So we need to ask ourselves, is government doing its job properly? If not, how can that be corrected? Is the answer to instruct government to review its policies and assumptions, revisit its structures, funding, and approach, and ensure that we are being provided with adequate health care in an efficient matter? Should we consider allowing other social institutions, including for example non-profit and other benevolent associations, or even private, for-profit entities, to have a greater role in the provision of health-care services?”

Marquardt said it is the responsibility of citizens in a democratic social to answer those questions.

“It would seem,” he said, “that prayerful reflection ought to be a part of our responses.”