Catholic Vancouver March 28, 2018

How nuns, mysterious health crisis influenced Providence CEO’s career

By Agnieszka Ruck

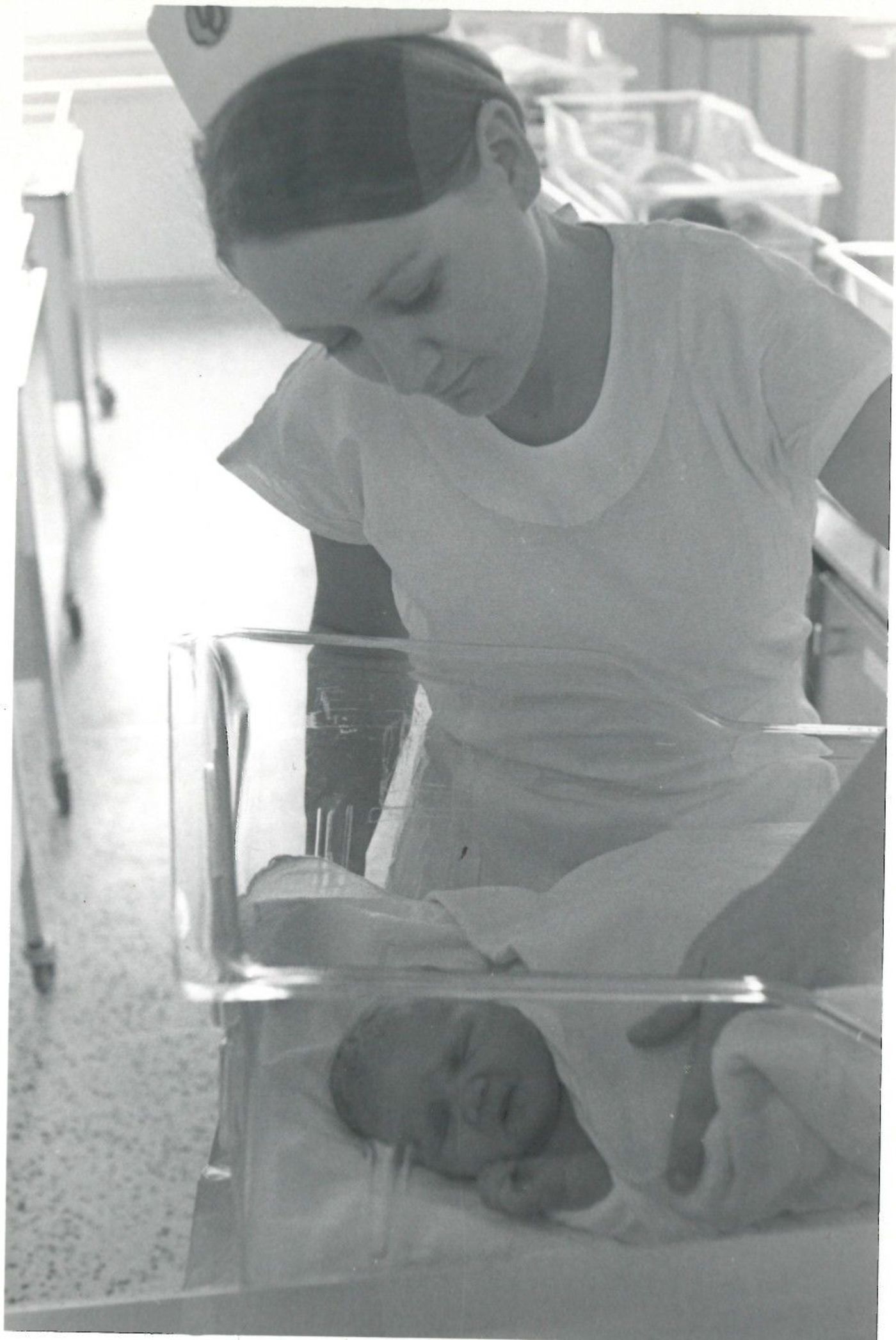

Dianne Doyle at her graduation from the University of Ottawa in 1973. (Photos courtesy of Providence Health Care)

VANCOUVER—It was the early 1980s and Dianne Doyle, a fairly recent graduate from nursing school, had just been hired at St. Paul’s Hospital when a grave disease struck.

“These young, mostly men at the time, had horrible respiratory illnesses and skin inflictions and nobody really knew, at the beginning, what this was,” said Doyle.

“We saw many people die quite quickly of this disease, including a number of people who were working at St. Paul’s,” she said. “There was fear, concern, and a lot of grief.”

Doyle, who retires next month as CEO of Providence Health Care (which operates St. Paul’s and other Catholic health care facilities in Vancouver), didn’t work directly with these afflicted patients at first, but was sucked into the grip this mysterious disease was tightening on the community.

One of her fellow nurses “in a short period of time went from being a colleague that was working with us, to being ill, to being dead.”

The illness that took many patients and nurses would be soon identified as HIV/AIDS, and St. Paul’s, which treated the afflicted in a ward code-named 10C, would become the birthplace of B.C.’s Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS and a world leader in research of the disease.

‘Little piece of my heart’

When Doyle thinks back to that frightening time, she remembers the sisters who founded St. Paul’s in 1894 and who provided hope in that dark time more than 30 years ago.

“The sisters were so inspirational because they had a ‘just do it’ and ‘of course we’ll do it’ attitude,” she told The B.C. Catholic during an interview March 23.

The Sisters of Providence felt an obligation to care for patients with this unknown, then stigmatized, disease, saying: “If not us, who?”

Doyle said the nuns gave “hope and meaning” to the lives of people with HIV/AIDS even when the causes and transmission of disease were still unknown.

And it wasn’t just patients in Ward 10C who experienced the loving care of these nuns. Doyle herself became a patient at St. Paul’s three times, while delivering each of her three children.

“It was not just: ‘Are your bodily needs being looked after?’ But also, ‘It’s a big transition: a first child! What’s that feeling like for you?’”

That focus on holistic care inspired Doyle and permeated the health facility. “There was a sense of comfort, that things are under control in the organization because the sisters have a presence and a sense of comfort.”

The sisters had a dramatic influence on Doyle in the early years of her career. “A little piece of my heart will always stay at St. Paul’s.”

Becoming a CEO

When Doyle graduated from the University of Ottawa in 1973, she never planned to become the CEO of a health care organization. She just knew she wanted to be a nurse.

“I cannot remember a time that I didn’t know I was going to be a nurse. Five years old? Six years old? I don’t know. I just knew I was going to be a nurse,” said Doyle.

Whether it was built into her DNA or being a middle child taught her to be caring and patient from a young age, Doyle says, “there’s something innate in my personality, where I’m driven to do something to help others.”

Doyle started her nursing career in the intensive care unit at Royal Jubilee Hospital in Victoria. A few years later, she moved to Vancouver and started working in critical care at St. Paul’s.

Raised Catholic but having drifted away from her faith, it was only at St. Paul’s that Doyle for the first time considered working in faith-based health care. “As I saw the values of compassion and social justice lived out in this organization, it so resonated with me and somewhere at the core of who I am. I guess they were there and I suppressed them in some way.”

Doyle worked in several Providence care centres before becoming the organization’s CEO in September 2006. Moved by its foundresses and those who decades earlier treated HIV/AIDS patients when no one else would, Doyle continued seeking ways to help people on the margins.

“I started to hear, early on in my time as CEO, some concerns being expressed by First Nations about how they were being treated when they came into our facility. That was my cue,” she said.

“Unfortunately, the First Nations communities are overrepresented in terms of the issues of homelessness, poverty, mental health issues, IV drug use, and addictions in the Downtown Eastside.”

‘No point in curing’

Doyle sought out ways to reach out by creating an aboriginal health team, partnering with the First Nations Health Authority, creating sacred spaces, and inviting First Nations elders to sing and be present at significant events.

“We need to do reconciliation work with First Nations and we need to give them preferential treatment because there is so much inequality in access and health outcomes for them.”

In 2010, another vulnerable population came to Doyle’s attention. “There were some incidents a number of years ago in the Vancouver area in which, tragically, infants were discovered abandoned in dumpsters and other circumstances,” she said.

An obstetrics doctor, Geoffrey Cundiff, suggested creating a place where poor mothers worried about their ability to care for a newborn could leave a child, anonymously, at the hospital. Angel’s Cradle was born, and two children have since been saved thanks to this service.

Now, as Doyle looks toward retirement, she trusts the Catholic health care organization will continue to reach out to the margins and provide the care that inspired her as a young nurse.

“Everybody says they are committed to holistic care, but look at their behaviours and what kinds of things they fund. If you’re not funding spiritual care, or if you’re not funding initiatives or resources that allow you to spend time bringing meaning into somebody’s life … then you’re not really doing holistic care,” she said.

“There’s no point curing somebody’s illness, providing surgery that corrects something, if we discharge them and they’re still a broken person.”

Doyle shared her reflections on her time at Providence during the Annual Provincial Prayer Breakfast with 900 politicians and local leaders at the Hyatt Regency Hotel March 23.

She will retire in April. England’s Fiona Dalton, with 23 years of experience in health care administration, will then move to Vancouver to take over as the new CEO.