Voices July 21, 2021

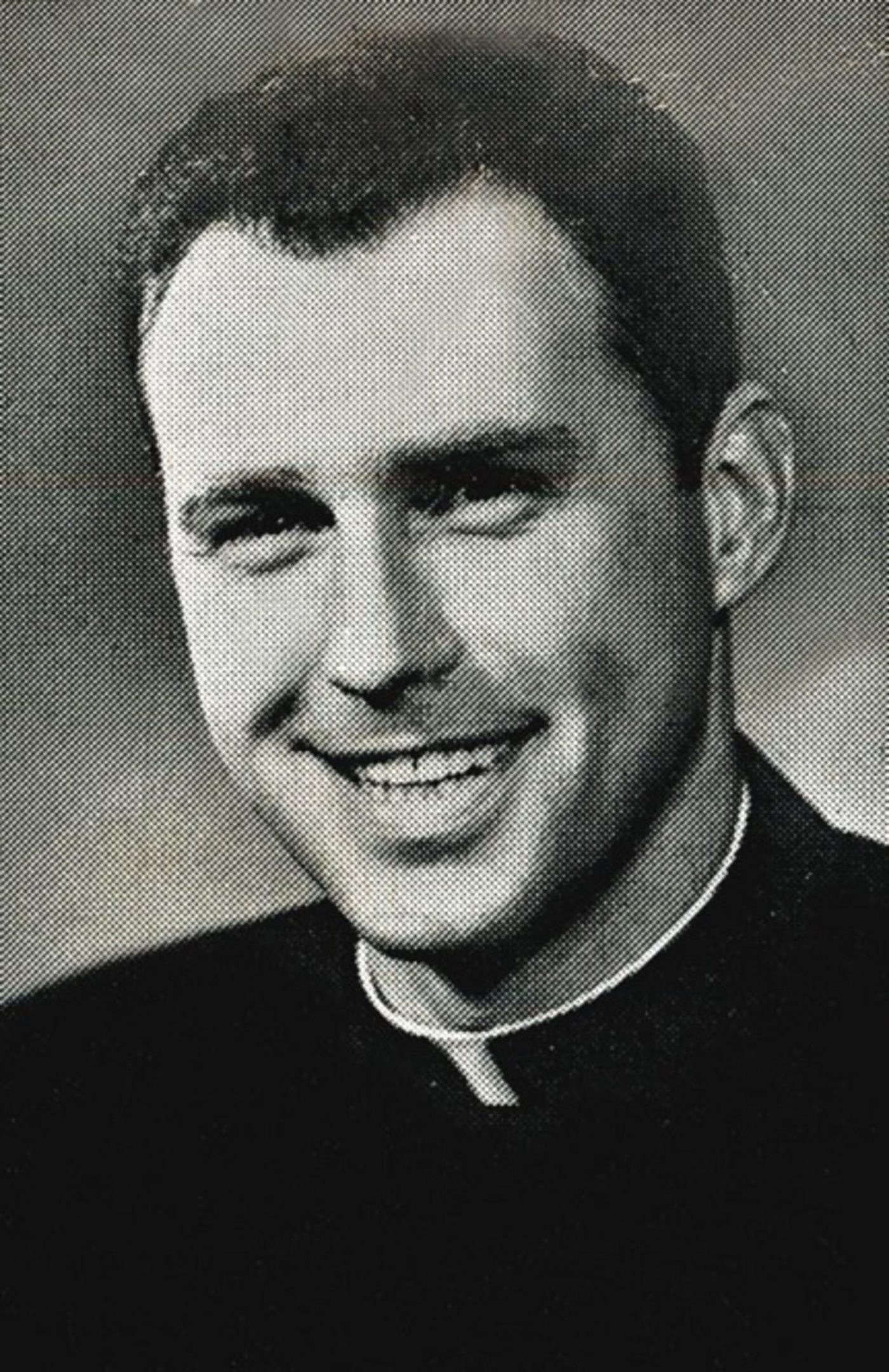

Father Somerville mirrored Pope John Paul II as a suffering servant

By Msgr. Gregory Smith

My earliest memory of Father Bill Somerville is Sept. 18, 1984. He was the master of ceremonies welcoming the crowd that greeted Pope John Paul II at BC Place Stadium.

That night was the only personal contact between Father Bill and Pope John Paul. Their lives and ministry seemed to have little in common, with St. John Paul leading the Church till his death in 2005, by which time Father Bill had already been incapacitated for more than a decade.

In fact, Father Bill and the future saint taught a similar lesson to God’s people: St. John Paul for the last several years of his life and Father Somerville for almost 27 years of his.

The lesson is the dignity of human suffering. I would go so far as to add the particular dignity of priestly suffering.

Both men, in their prime, were models of energy and accomplishment; but in their decline they taught just as vigorously as they did at the height of their powers.

Less than seven months before his historic visit to Vancouver, St. John Paul wrote that suffering “is a universal theme that accompanies man at every point on earth: in a certain sense it co-exists with him in the world, and thus demands to be constantly reconsidered.”

In his very public suffering, St. John Paul invited the world to reconsider suffering and its meaning. His Calvary, accomplished in full view of the world, demanded consideration by those who believed that God should treat his faithful servants better than he does.

In his more private suffering, which was nonetheless well known to his former parishioners and fellow priests, Father Bill also became an icon of the suffering servant. It was impossible to have known him in his prime and not to question the meaning of his long suffering.

Our reading from the Book of Lamentations begins with words of affliction we could place on the lips of the suffering Lord, or of Father Bill: “I have forgotten what happiness is;” and “Gone is my glory, and all that I had hoped for …”

And in the second reading, St. Paul uses labour pains to describe the existential suffering experienced by all creation and even by we ourselves. We groan together with creation, as we wait for the redemption of our mortal bodies, so subject to suffering and decay.

Both readings redeem their darker verses with overpowering light. The Lamentations passage has two equal themes: crushing distress provides the first half, but in the following verses the prophet abruptly takes his feelings in hand by calling to mind what he believes.

Faith becomes, therefore, an antidote to his pain and discouragement. He knows that “the steadfast love of the Lord never ceases” and so chooses to hope in him, to wait for him, and to seek him.

Rejecting any quick fix or miraculous solution, the anguished prophet concludes that it is good to “wait quietly for the salvation of the Lord.”

St. Paul weaves this message of hope into our reading from his letter to the Romans. He reasons that present sufferings must be weighed or compared against future glory.

Without the promise of future reward, without the sure hope of an inheritance with Christ, human suffering is not only without value but to be feared and avoided. Yet in very few words Paul sums up what we believe: we suffer with Christ “so that we may also be glorified with Christ.”

Against the background of this fundamental truth, all who knew Father Bill Somerville could see him living out the words of St. John Paul, who said that suffering “is as deep as man himself, precisely because it manifests in its own way that depth, which is proper to man, and in its own way surpasses it.

“Suffering seems to belong to man’s transcendence: it is one of those points in which man is in a certain sense “destined” to go beyond himself, and he is called to this in a mysterious way.”

Father Bill’s destiny, in which so much of his priesthood was spent preaching the gospel of suffering, did go far beyond himself. But today we must read the final chapter by recognizing the ultimate lesson of his life and death.

St. John Paul’s letter on human suffering, called Salvifici doloris in Latin, sums up the lesson, quoting the same text from Romans we heard this morning: “those who share in the sufferings of Christ are also called, through their own sufferings, to share in glory.”

Some of us may have asked the Lord the question “do you not care?” as we prayed for Father Bill – indeed he may have asked the question himself. Today the word of God provides a one-word answer in the Gospel account of the calming of the storm. That answer is “Peace!” Jesus says to us what he said to the wind and the sea: “Be still!” He might well have finished that quote from Psalm 46: “Be still and know that I am God.”

Dr. Mary Healy has called this miracle one that reveals the awesome power of Jesus over “all the elements that cause fear and distress in human life.” As we ponder the years of Father Bill Somerville’s priestly life, more than half of them spent in illness and suffering, we rejoice that our faith allows us to see the power of Jesus at work in his life and in ours, bringing peace in the midst of suffering.

Filled with the same awe as the disciples on the Sea of Galilee, but with the added gift of faith in the Lord’s Resurrection, we rejoice that the winds and waves are now calm for our brother.

We give equal thanks for the two halves of his priestly life: the first, during which he built up Christian communities so strong that those of us from St. Pat’s feel a lasting bond with each other and with our pastor, Father Bill.

And we are grateful that the second half, the season of suffering, called us to be people of faith, as Father Bill had challenged us during his more active ministry.

From a homily preached by Msgr. Gregory Smith at the funeral Mass for Father William Somerville at Holy Rosary Cathedral on July 20.