Voices July 14, 2022

Important distinctions are needed about residential school history

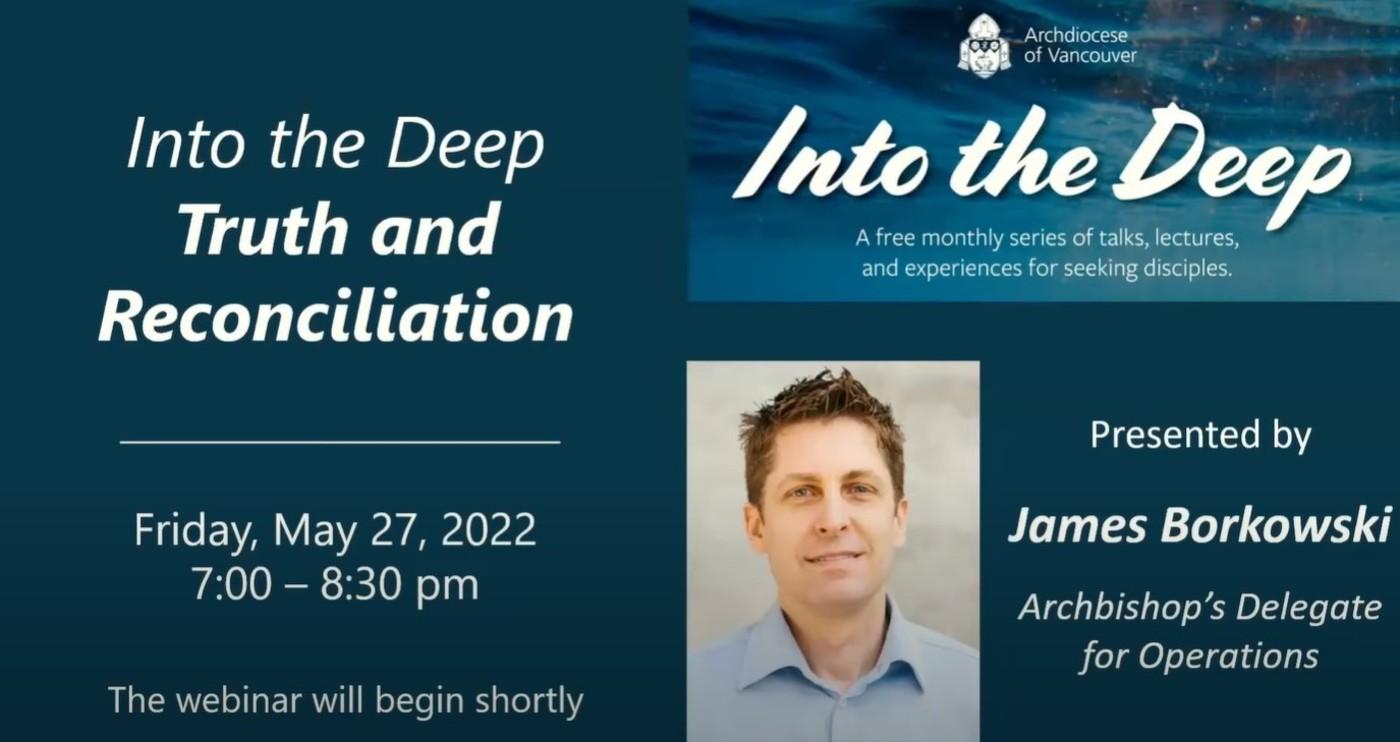

By James Borkowski

In the final section of his presentation on the work of reconciliation with Indigenous people, James Borkowski looks at some background about the residential school system that many people haven’t been hearing. His full presentation is on YouTube.

Part VI: Some important distinctions about the residential schools story

I want to share some other facts that you may not be hearing, and I can do this because – as many First Nations leaders have said, including ones we’ve met with – without truth there can be no reconciliation. Some of these were surprising to me and I want to share them.

The first is that many of the First Nations people we have met with want us to know that when people are shocked and outraged by the news of possible cemeteries at schools, it hurts them deeply because it confirms that people did not read or care enough about the Truth and Reconciliation Report. It was all in the report.

The TRC issued a death registry containing the names of more than 3,200 children. The TRC said they couldn’t find records regarding almost 1,400 of them, and of the remaining 1,800 students, 832 are recorded as having died at the schools over 110 years of the school system. Another 418 died at home and another 427 died in hospitals. The remaining 100-plus died in other locations.

Since that report came out earlier this year, a group of scholars has located many death and burial records of these children, especially those listed in the unknown category. Quite a number listed as being buried at residential schools have also been located in their home community cemeteries. This should be a little bit of comforting news for families who may have had questions about a relative. We’re hoping that this gives them comfort.

In the end, the number of children who died while at school might be higher and it might be lower. The key is we need more research done so that everyone knows who each child was and what they died of.

Another surprise to some, according to a UBC based research report that came out before the TRC process: Under seven per cent – 6.7 per cent – of all abuse claims in residential schools were against priests and sisters. A lot of Catholics and a lot of non-Catholics report that they assume the vast majority of the abusers were religious and ordained priests. It is small consolation to the victims of these horrible crimes, but I think it’s an important distinction that more than 90 per cent (of abusers) were lay teachers, lay staff members, and even a lot of children reported abuse from older students. Again, that doesn’t let the Catholic entities off the hook. They were the ones responsible for the safety of these children and did not deliver on that obligation that they took on.

I spoke earlier about Indian agents. An interesting point I found is that by 1927 the majority of Indian agents were Indigenous people. There’s extensive historical writing about the tension between Indian agents, government officials, and Church representatives, and the government quickly learned that hiring members from First Nations communities reduced the tension and made school attendance more likely. One equated it to thinking of Matthew as being a tax collector among the Jews, and that is how many Indian agents were viewed by their home Indigenous communities.

Another fact that might surprise some is that by the 1930s many of the residential schools had Indigenous teachers and staff members, and this was often a result of these teachers being educated themselves at missionary schools. As the early missionaries had hoped, some Indigenous students came back to teach.

I’ve also heard a lot of talk about how Indigenous children should have been educated in their own language. As you heard earlier, this was done in many day schools. Why couldn’t it be done at residential schools? I asked that question.

I then met with some former staff members of one residential school and they had an explanation. Before it opened there was a discussion between non-Indigenous and Indigenous staff members. The non-Indigenous settler teachers asked about the possibility of teaching in the native language. They found out quickly the Indigenous staff member made two arguments about that. First, the school drew from six local First Nations communities in the region. That meant six different languages, so the Indigenous teacher asked how would that even be possible?

Secondly, the schools were proposed as preparation for students for a rapidly changing world, and the Indigenous teachers argued at times that these kids needed to learn English if they were going to have a chance to succeed. The belief at the time was English-only would enhance their ability to learn the language quicker. Again an error, I think, but understandable why it wasn’t as easy a decision as some may think.

Interestingly, one teacher I met with still committed to learn new words from each of the six languages each year so that she could communicate with and even comfort the young children. Many of the sisters of Saint Ann and priests also learned Indigenous language against the wishes of the government. Remember, by the 1930s and 40s many of these missionaries and their orders had spent generations learning these languages, sharing the Catholic faith in them, and even translating books back and forth.

An interesting point I found is that about 30 per cent of all Indigenous children attended residential schools. Of the 70 per cent who didn’t, about 30 per cent went to day schools, mostly on reserves, and about 40 per cent of Indigenous children during this period had no school-based education at all. And that included large parts of the country. So according to various reports the children from the non-residential school categories did not experience better outcomes socially, economically, and certainly not educationally.

As Pope Paul II stated almost 500 years ago, Indigenous people should not be deprived of their liberty or their possession of land. As Catholics, we are called to be aligned with Indigenous people anytime they are treated unfairly. Paul Tennant wrote a very important book: Aboriginal Peoples and Politics. Another is A National Crime by John Malloy. These books go into great detail about some of the real battles that Indigenous people were facing throughout the history.

So how does all of this relate to what broke in Kamloops last year? This is the hard part. When you hear that more than 1,300 children’s bodies have been found at residential school cemeteries around the country, it’s not true. No unmarked graves have been found yet outside of existing marked cemeteries. Most of the headlines regarding new graves found have already been properly disproven, so lots of time has been spent and funds have been spent on properties in Edmonton, Saskatchewan, Cranbrook, Nova Scotia, Ontario, and northern B.C., all not turning up what they thought they would find.

I want to state clearly we know that children are buried at some of the residential school sites, but nobody has located any yet and we need to be patient in this matter. Kamloops, as an example, just announced that they are going to start the exhuming process and this can take a long time. But they deserve our patience, our support. We are waiting for them to tell us what we can do to help with their process.

Some elders find this idea very traumatic, and others desperately want these remains found so that they can be sent back to their communities of origin. And I think we need to be compassionate and listen well.

Archbishop Michael, working with Bishop Joseph (Nguyen of Kamloops) have also offered to help cover the cost of DNA testing to provide these families with comfort and closure regarding what those children died of.

Longtime secular journalist Terry Glavin wrote the most comprehensive article to date, and it was published in The National Post. The headline is The Year of the Graves: How the World’s Media Got It Wrong on Residential School Graves. He is no defender of the Church, certainly no defender of the residential school system. But he does a site-by-site walkthrough about what was reported and why.

I think it’s an important read, not to defend the Church or to defend the system, but to understand what’s going on in our culture, and especially about our rush to judgment and sometimes misplaced judgment. The New York Post published a similar one I would encourage you (to read). This is pushing back against the narrative to make sure the truth gets out while being pastoral and while understanding that the system was flawed and that many children and families had their lives destroyed by it.

On reconciliation and the path forward, I think we’re being challenged today as Catholics to become the third wave of missionaries in this region, and the question is will we will look more like the first wave where we meet people where they are at and listen better and bring the faith to communities that are asking for our help? Or will we take a more institutional approach? Will we respect their language and culture, or will we barge in with our own?

I’m very thankful that Archbishop Michael and others have led with wisdom and humility in acknowledging the flaws of the residential school system. We don’t have to be defensive about the mistakes made and I find when we acknowledge them, we can challenge the secular narrative of murder and of body counts. Instead, we can focus on the wrong which was the separation of children from families and the multi-generational trauma that resulted.

One of the reasons that is so important is that that separation of children from families continued after residential schools were shut down. So the government, sometimes in justified cases, but all too often, were removing Indigenous children from their homes, and that is the same system that we need to work together with Indigenous communities to stop today.

Some quick recommendations in our last couple of minutes:

- Please read the TRC report, especially the calls to action. They are a good starting point. We’ll also send you this reading list that can add to that for those of you that want to learn more.

- I have to often remind myself that prayer is not what we do when we can’t do anything real; prayer is the primary way for us to welcome God’s grace and healing into this process. So let’s pray for Indigenous people struggling with trauma and all of its related problems. Let’s pray for Indigenous leaders and families and counsellors and advocates. Let’s pray for people working side by side with First Nations people to help them heal and find justice. Let’s pray for the Pope, that his health holds up and that he can be here in July. Let’s pray for all of the Indigenous Catholics in this region and across the land. Many are reporting feeling unsure of where they belong; some face pressure in their Indigenous communities and some feel a real sense of unease in their Catholic communities. And lastly, let’s pray for each other that we grow in humility and patience and trust God in this matter.

- Another thing we can do: be generous. Thanks to your generosity and the collection carried out last September, the archbishop has committed $2.5 million to the cause of healing and reconciliation, and a Metis spokeswoman at the Vatican last month was very touched by the generosity of Catholics and stated that each donation is a personal act of reconciliation. So thank you for your generosity.

Locally we have an Indigenous majority committee that is reviewing grant applications and we’re very close to approving the first projects, which can lead to additional healing in this region.

What else can Catholics do? Consider inviting elders to come and share their stories. Again, our primary job is to listen and to hear how we can actually help. We have to be very careful to not propose solutions without being asked.

Another one: let’s get good, challenging curriculum into our schools. One of the things that scares me the most about this issue is I hear a lot of young people assuming “old people bad, young people good.” Or “Church evil, it’s obvious, look at the past.” We need to help our kids learn from the actual truth so they can help avoid similar mistakes.

We need to bring in resources like we are discussing tonight. We have some through grants that will be coming to every parish, but there are good books, good movies. Father Larry Lynn in our diocese made a film called In the Spirit of Reconciliation and it’s available to show at your parishes. So please consider continuing on this learning journey.

Lastly, this sound cynical but I mean it in the most optimistic way. As a Church, we need to not rely as much on corporations and governments. We are called to be in this world, but not of it. We have to be fearless about standing alone at times. I think we’ve learned our lesson and we should be ready to support the marginalized in our community each and every time. In this case it would mean standing with Indigenous people and at times opposing government policies when they are unjust.

In conclusion, we can live our faith like Jesus did and like many of the early missionaries did. We can meet people where they are at. When we enter into real relationships, it opens the door to witness and the chance to invite someone on a path to healing and a path to the God who became one of us, the God who offers true reconciliation.

So the residential system was more complex and nuanced than we may have been hearing. There were great saints and unthinkable sinners, and I want to close by saying there are not two sides to this issue; there are more than 150,000 stories to be heard on this issue – one for each student who attended, and more for the families and communities that were impacted by residential schools. Whether their stories are heartwarming or heart breaking, or both, they deserve to be heard.

As we mark this one-year anniversary of the news in Kamloops, I hope we as a Catholic community can commit to seeking truth and charity and increasing our efforts to get to know and love our Indigenous neighbours better than we do right now.

Part V: Schools had more students but same funding

In an 1892 report on the Kamloops Residential School, the government funding model was described. “The federal government granted funds to Kamloops Indian Residential School on a per capita basis to cover the cost of feeding and clothing the children, maintaining the school, and paying the staff. In 1895, when the school had 25 pupils, the government grant was $130 per capita per year to cover all expenses. Ten years later, in 1905, the grant remained the same but had to cover the cost of 60 children attending.”

This was a regular cycle; the government was consistently falling short. Every five to 10 years they would increase the allowance, but only to catch up with the attendance that had been in place five to 10 years earlier.

The Church could have seen this government failure early on and walked away. Instead, Catholic orders, each and every one of them, protested, sent letters, lobbied however they could. They raised whatever funds they could from local Catholic communities, but they continued in this system.

I want to break down the teacher shortage further. Why were they hard to come by? What history shows is that teachers moving on to reserves in the 19th and even into the early 20th century did not tend to personally thrive or last long. The winters, especially when we get to Kamloops and further north, were brutal. Almost endless work was there for teachers. Many had to double as janitors and as handy people. Often teachers reported a deep sense of isolation and loneliness. Those First Nations that could recruit teachers had great trouble keeping them, so this resulted in what I think was the Church’s big second mistake: religious orders were now in a position to educate more Indigenous children than in the first Catholic wave (but) the government was providing far less pay than teachers received in Vancouver.

So when the teacher shortage resulted, where did Catholic entities hire from? There were not enough priests and sisters to cover the need. So the answer was: they searched and hired from some regrettable places. They advertised in European journals. They accepted travelling journeymen. They accepted some deeply flawed priests. Many great people with missionary hearts came forward and I have met several of them, but some predators and abusers also entered the system. They saw an opportunity to enter and exploit, so we ended up with schools that lacked adequate resources and proper supervision and Indigenous children and families were hurt as a result. Many children were physically, sexually, emotionally, and spiritually abused, and I think as Catholics we need to be very careful to not skip over that point in any way. Real lives were destroyed and that cycle of trauma and abuse is a very hard one to break even to this day.

So in this second wave, almost all Catholics did their best, but the system was broken and wrought with risk. And as if that weren’t enough, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries infections and pandemics swept through this region. One report regarding Kamloops – and this again cites a lack of funding leading to more problems – staff recognized that one factor adversely affecting the children’s health was the condition of the 30-year-old rapidly deteriorating wooden school buildings. Lack of renovations which were on hold due to lack of funds resulted in poor hygienic conditions. Their worst fear was realized when one of their girls became ill of an unknown cause. She was taken to Kamloops Royal Inland Hospital on April 19, 1918, where she passed away June 3, 1918.

The Sisters of Saint Ann in particular – and there’s a wonderful book that we’ll make available in some of the reading resources we provide – these sisters talked of and thought of (the students) in their recorded histories like their own children. We’ll talk a little bit more about that later.

Prior to the advent of antibiotics, influenza, pneumonia, and tuberculosis were scourges that affected all sectors of the population. Among these, the Spanish influenza of 1918 was particularly deadly, killing millions worldwide. Surprisingly, neither the children nor the staff at Kamloops School contracted the illness. However, the disease did strike some families on the reserves. As a result, children were prevented from making their annual visit home on Christmas Day. In an attempt to ease both the children’s and the parents’ disappointment, the sisters invited relatives to visit. They transformed the girls’ recreation room into a parlour where parents and relatives enjoyed time with their children and, in some cases, former teachers.

In another letter, Kamloops Principal Father McGuire wrote to Indian Affairs, “Your miserable accommodation here for small boys I had to tear down as it was condemned by the public health officer.”

After prolonged pressure from the Oblate Sisters of Saint Ann and the Indian Affairs chief medical inspector, the government acquiesced and a new school building was constructed in 1923 on the school site.

In attempts to alleviate some of this financial pressure, the sisters often raised funds by holding benefit dances, organizing bazaars, and giving concerts. The Catholic Church Extension Society also supported the school through donations of money and Christmas gifts to children, but it was never enough.

The government then changed the Indian Act in 1921 to make school attendance mandatory for Indigenous children. Another layer of trouble was headed the Church’s way.

The federal government carried out this attendance policy by hiring hundreds of additional Indian agents. These agents were now given the authority to penalize families and communities if their children didn’t attend school. In some cases, children were even forcibly removed from their homes.

These policies led to more trauma for the children, their families, and their communities, as well as more stress on the already limited resources for the people trying to provide the education. During this time, there were increased reports of runaways and even suicides among the students. These deaths were well recorded by local media, and I again invite you, I implore you, read the available histories. We will send a lot of them out to anyone who is interested. But there is a lot of good information that really shows despite racism, despite paternalistic views, there was caring from the general community, and especially from the Catholic community for the wellbeing of Indigenous communities. A lot of people were doing a lot of good in trying. That is not defending the system, which I’ll go on to explain I see as deeply flawed.

More provincial legislation in what is now British Columbia allowed Indigenous parents to start sending their children to public schools. By the mid to late ’50s, most public schools were fully accessible to Indigenous students. From then on parents actually had to apply to get their kids into residential schools. Surprisingly to many of us, most residential schools remained full until they were closed down, some in the 1970s, some in the 1980s.

During these later years, while disease may have lessened, residential schools were into multiple generations of students. In some cases the fifth, sixth, and seventh generation of students had been sent away to schools, and the impact on Indigenous families was severe in several ways. We saw 100 years of broken families, 100 years of disconnection between generations. We saw the continued loss of language and culture from Indigenous communities.

When students went home for Christmas and summer, they often reported feeling as though they didn’t belong at home or at school. Imagine those children growing up later, trying to enter marriage and start a family when they didn’t see enough of their parents and didn’t learn how to parent.

I think we’re being called to let that reality deeply hit our hearts and not to ever think that this is just a matter of people pulling up their socks and moving on.

Catholic orders were mostly out of the school system by the late 1960s and after that the government ran these schools right up until the last one closed in the early ’90s, so they were publicly funded and publicly run for about the last 25, 30 years.

Final part next week.

Watch the full presentation on YouTube.

Click here to send a letter to the editor.

Part IV: Imagine walking into a residential school at age 5

By the late 1800s, many First Nations community were experiencing what sociologist Emile Durkheim called “anomie,” which is a breakdown of social order driven by uncontrollable change, especially regarding how people work and how families lived. He noted negative impacts on marriage and family employment levels, health outcomes, substance-abuse challenges, and other problems. Entire cultures could be swept into dependence and despair when this kind of upheaval occurred.

So along with championing Aboriginal rights and title, early missionaries worked with Indigenous leaders to create efforts to curb the rise of alcoholism that rose as unscrupulous traders pushed liquor onto communities.

Where I believe Catholics got into trouble in this second wave with residential schools was in the institutionalization that occurred in partnership with government, and we can see how this temptation came into play. Instead of boldly bringing the faith and education to Indigenous people in their communities and in their languages, Catholics allowed the government to build schools for us and to implement often-coercive systems that delivered children to these schools. That was an error in many minds and the effects are still being felt today.

In some ways, the Catholic participation in residential schools took us off-mission as a Church. We became more aligned with government and with what was referred to as “polite society,” and that impacted how Catholics saw the people we were called to serve.

The Church became a part of the establishment and we were asked to treat Indigenous people as a monolithic problem to solve instead of a diverse group of individuals and cultures to serve. I think some leaders of religious orders picked the wrong partner, no matter how good their intentions may have been.

This is from another historical report: “It is not surprising, therefore, that when the federal government assumed responsibility for Indian schooling, it made funds available for boarding schools. The federal government's position on this matter undoubtedly influenced the Jesuits’ decision to obtain funds to build boarding school facilities … in1868 in what is now Ontario, and this development likely influenced the Oblates to seek federal grants for similar ventures.”

We can see the temptation coming from the perspective of wanting to educate more children and also finding ways to create more efficient and sustainable systems. But again, I think it was the source of one of the biggest mistakes made. Catholics have never sought out the orphanage model and should not have sought out the residential school model for young children. We are called to be there for children when trauma has caused a tragic break, so, as an example, wars and natural disasters, disease. Orphanages should be the last resort and they should be an authentic attempt to provide or restore a little bit of what the children have been robbed of.

So I think mistake number one: the Church erred in thinking that residential schools were better for Indigenous children and families than the alternatives. The religious orders could have limited themselves to teaching fewer children but staying committed to teaching in Indigenous communities. Again, I want to emphasize that would have meant that tens of thousands of Indigenous children would have gone without education. So there was likely hardship coming either way.

So several Catholic orders participated in the school system that facilitated the separation of children from families, and that is a serious violation of Catholic social teaching. Our Church teaches that it’s clear parents, not the state, and not a religious order, are the primary educators of their children. So again, no matter what the motives may have been, this led to occurrences of sexual and physical abuse, neglect, and disease under the care of Catholics.

But I want to make it more personal than that. I would like to do what’s called a right-brain exercise. Walk back in your memory if you can, all the way to when you were five years old. Think of your kindergarten teacher or an early birthday party. Can you picture your 5-year-old self?

I’d like you to imagine walking into a large room with two rows of beds, 10 beds in each row.

You are new to the school and you were assigned to a bed on the far-right side of the room halfway back. You walk over to it and sit down. It is squeaky and uncomfortable. Hear the sounds and remember the feel of an uncomfortable bed you’ve sat on. The room is very cold, so when you breathe out you can see your own breath. Now imagine it’s 8 p.m. and the lights go out and you see the last sister leave the room. You are trembling from the coldness and the fear. You hear the cries from several homesick children and it makes you immediately homesick. Others are whimpering. You hear some older kids teasing the younger ones. You smell sweat and you smell bedwetting. You are hungry and scared. You try to fall asleep, but the fear keeps you awake. You hear some kids coughing and sniffling. Most importantly, you wonder where your parents and grandparents are at this very moment. Do they miss you? You wonder why you are here. Are you going to see your family again? You try to think of better times at home, but you know, at least for a while, this is your new reality.

It took me a long time coming out of the exercise here. It took me a long time to even be able to think about what my life might be like if my parents and grandparents and great grandparents and great, great grandparents had all been through this experience. I remember as a child, I cried on the first day of school every year until at least Grade 5. And I got to go home six hours later.

The reality of the residential school as a family-breaking system is staggering if we can personalize it for us.

I want to go back to the history. The Indian Act required the federal government to provide funds and teachers for schools built on reserves and for these regional residential schools. It’s interesting to note, most First Nations communities had schools on their reserves. So why didn't all children just attend those schools? The primary answer that I have found in my research is that the government failed to provide the teachers it promised, and it gravely underfunded the schools that had been built. That led directly to death and tragedy.

I want to read an excerpt from a report on the Kamloops Residential School, which we’ve all been hearing a lot about. This is a report from 1892. “Problems arose between the government-hired principal Mr. Hagen and the Sisters of Saint Ann when the principal imposed perpetual fasting on the sisters. This was a budget-cutting exercise, severely limiting their food. As a result of various problems including him denying them a chapel, the sisters were withdrawn. The Kamloops school closed in June of 1892 with Mr Hagan’s resignation.”

Now, of course, the sisters came back and we’ll hear more about that later. But we could already see the tension between government and Church very clear in the history when residential schools started.

Part III: How the Indian Act changed everything

To be clear, the settling of this region that we hear about a lot today was colonialist in nature and there is little doubt from the recorded history that the corporate and government goals included taking the land and resources, however necessary.

When Catholic missionaries cared for the people they served, they were actually aligned with the rights and interests of the marginalized – often opposed to both government and industry. So Father Le Jeune for example was asked to serve as the secretary for the first association of chiefs in this region. The chiefs deeply trusted him, and a lot of very strong friendships existed between early missionaries and Indigenous people.

Here’s an excerpt from another report: “Until the late 1860s, at least, Catholic Indian School programs differed from their counterparts whose institutions were primarily boarding schools conducted in English, and their teaching staffs were largely if not entirely non-Indian.

“Jesuit and other Catholics decided that fluency and literacy in an Indian language followed by reasonable levels of competency in English and French were essential components in training Indians to become candidates for teaching positions.”

Now this was not well received by the colonies’ Indian administration or by school inspectors. There is evidence that this resulted in much lower funding for Catholic schools.

There were great Protestant missionaries as well. In 1820, in what is now Ontario, a minister named John West began by boarding 10 Indian children. But it was not long before he found himself at odds with Hudson’s Bay Governor George Simpson over such matters as the company’s sale of liquor to Indians. This report goes on to say, “a minister’s attempt to school Indian children added to the governor’s misgiving about the missionary.”

As the governor put it, “the Indigenous are already too much enlightened and more of it would do harm instead of good to the fur trade. I have always remarked that an enlightened Indian is good for nothing.”

Simpson, the governor from Hudson’s Bay Company, his dissatisfaction with missionaries extended to the Catholic Church as a whole. In 1841, he wrote the company’s headquarters in London about the need to check the Roman Catholic influence, which, if allowed to remain unchecked, would become extremely injurious to the company’s interest.

In 1839, he asked other denominations to come to the country on the understanding they would not engage in dangerous social experiments. And what were the dangerous social experiments that he was discussing? They included teaching students that they were equal in God’s eyes, teaching them that they were overly capable of significant learning, and we know that Jesuits and other orders taught them that they were worthy of the same love and happiness as any other person.

So what went wrong? There were certainly examples in this first wave of Catholics acting in paternalistic and even abusive ways. So the first wave had some bad people, but the recorded histories, including from the voices of Indigenous people, suggest that in many ways it was a promising start. They were able to fulfill the mission of the Church and respect non-Christian people.

I do think it’s important for us to note that evangelizing well is not something that the Church ever needs to apologize for. We’ll come back to that later.

Moving to education, I was very interested to learn that many of the early missionary schools up to the mid-1800s were attended by Indigenous and settler children together. That system was also voluntary for Indigenous students.

Again from the article by historian Robert Carney, there are indications that those who went to school did so with the consent of their parents or guardians and that they could be removed from the school whenever their parents wished. Moreover, the latter decision was frequently prompted by the pupils themselves.

In that first wave, we know that one of the goals of the religious orders at that time was to educate Indigenous students so that they could come back to their communities to teach at Indigenous day schools. Several missionaries wrote about the need for multiple generations to receive formal education in order for First Nations people to thrive and fully engage in what was rapidly turning into a very different world.

So while early missionary schools were serving First Nations and settler children together, they were only serving a fraction of both populations, and there was a growing demand for more education. In 1877 – right after the Indian Act was passed – it’s estimated that less than 10 per cent of Indigenous children of school age from 7 to 12 were being educated formally.

Many Indigenous leaders are on record in the mid-19th century, including as conditions in the treaties they entered into in Ontario and in the Prairies, demanding that their children have access to good education. They knew that it was critical for their children to not fall behind.

But there were many questions. Where would the new schools be? Who would pay for them? What ages would be included? And who would teach at them?

And then along came the Indian Act and the world changed dramatically again for Indigenous people. The act legislated who was “Indian,” how chiefs would be elected, how children would be educated, and how Indigenous people would acquire land mostly focused for agricultural purposes.

Among other things, the government promised full funding for schools, including teachers.

Let’s look closer at the second wave of Catholic missionary activity – and the reason I’m presenting this in two waves is to allow for a more nuanced understanding of the commitment and sacrifice made by almost all Catholic missionaries that came to this region. It would be heartbreaking to let these men and women go down in history being thought of as mostly terrible, and even murderous.

Pope Francis even acknowledged the many holy missionaries in his recent apology to Indigenous people, and this sentiment has been echoed recently by St. John Paul II and the former Pope Benedict the XVI.

Back to some historical context. Life for most people, including Indigenous people in the 18th and early 19th century in this region was very hard. Before first contact with settlers, it’s been estimated that 50 per cent of Indigenous children did not make it to their 21st birthday. Stillborn and infant death rates were very high for Indigenous and settler children. There were already these natural risk factors that were then compounded by new diseases brought by Europeans.

Both Indigenous people and early settlers were also at the whims of nature, which meant that a bad salmon run or early frost could make for a long and brutal winter. I want to add that many of the cultural plagues in our society existed in both settler and Indigenous communities even at that time. Both had abuse, neglect, violence, greed, and poverty. They were all there, and I grew up thinking that before the colonial process that people native to this region were living in a sort of Garden of Eden and that we brought all of the problems. In reality they were amazing and resilient people living in a very challenging environment.

Part II: ‘There were many saints and some terrible sinners’

As a warning, I will use historical terms such as Indian and Aboriginal, and I’m sorry if those are hard to hear, but I think they’re important for historical context, especially when we’re citing earlier works.

So let’s start with some history. The early missionaries in what I’m calling the first Catholic wave, up until the Indian Act of 1876, were best received by Indigenous communities when they worked independently from what is now called the settler movement.

Catholic missionaries started in eastern and central parts of this land and moved west. And like most of the people they came to serve, the missionaries were not a monolith. They were mostly Oblates of Mary Immaculate from France, and there were many saints and some terrible sinners, and they were as diverse and fallen and as complex as we are today.

So these early missionaries came to North America with the Church’s teachings regarding Indigenous people firmly in mind. Three hundred years earlier, as Spanish conquistadors slaughtered their way through what they called New Spain, Pope Paul III upheld and promoted the rights of Indigenous people. In his 1537 document Sublimis Deus he said, “The said Indians and all other people who may later be discovered by Christians are by no means to be deprived of their liberty or the possession of their property, even though they be outside the faith of Jesus Christ and that they may and should freely and legitimately enjoy their liberty and the possession of the property. Nor should they in any way be enslaved. Should the contrary happen, it shall be null and have no effect.”

That’s Pope Paul III speaking quite emphatically, stating how the Church felt on it. This was the prevailing Church teaching on this matter.

Many explorers and governments rejected that teaching and instead tried to reinforce earlier letters from Pope Alexander VI – often called the worst Pope in history. Alexander VI capitulated to the Spanish government’s demand that the Church at least mildly support exploration and the conquering of lands and people. His letters from the 1490s are often cited as evidence for what is sometimes called the “doctrine of discovery,” although it certainly was not doctrine. Pope Paul III’s decree 40 years later was clear papal teaching on this matter, more than 250 years before missionaries arrived in this region.

So when missionaries brought the faith to Indigenous people west of the Rocky Mountains, some beautiful things happened. They often worked side by side with the Indigenous to build schools, housing, meeting places, and, yes, even some churches. Catholic missionaries shared their knowledge about farming, education, history, and medicine, and the records from that time show that many missionaries were excited to learn the local language, custom, and traditions of the Indigenous people they served.

They also championed Indigenous people’s title and rights to their land and resources and fought with local government agents to ensure communities were protected against settler and government exploitation. Father Paul Le Jeune, perhaps the most well-known Catholic missionary in this region, was said to have learned more than 20 Indigenous languages.

The Oblates, the Sisters of the Child Jesus, the Sisters of Saint Ann, Jesuits, Ursuline sisters, and other orders were working and educating here by the early to mid-1800s.

Focusing on the Jesuits for a second – one written report by historian Robert Carney contained the following observations: In the 1840s, Jesuits followed certain pedagogical principles, including tact, infinite patience, and gentleness – in effect, a rejection of the European idea of childhood, which always saw the man in the child and which regarded childhood as a period of preparation, obedience, and discipline, often of a harsh character.

In another section of that same report, Carney described the Jesuit style of teaching Indigenous children. Children attending were taught in small groups and in their own languages. A variety of techniques were used to support such instruction, including simulated games, rewards, prizes, songs, and pictures.

Again, this is in the first wave of Catholic missionary activity. On the catechetical front, one of my favourite ideas that emerged at that time should still be very attractive to us today. Let me try and explain why the Catholic faith was appealing to some Indigenous communities 150 to 200 years ago. The first point is there is one God, and that God is the creator of everything.

Number two: when darkness entered the world, God loved us so much that he became one of us so that we could learn how to love the creator and each other.

Number three: Jesus, who is God, became human to save us. And did he enter the world as a conquering and powerful figure? No, he became the child of a modest family and was part of an often-persecuted people. He lived a rhythmic life, faithfully serving his family and his people.

Now this one I’m adding, but they did make a point of it at the time. Jesus was a Middle Eastern person of colour. I know that’s modern language, but the point stands that when the faith was shared in humility, Indigenous people were taught to see that Jesus was one of them and that he came for each of them. That was attractive for a lot of people, and it should be attractive to us.

The last point was: out of love, Jesus died for our sins because he was God. He rose from the dead and sent his disciples on the Great Commission, and that very commission was what early missionaries were bringing and presenting to Indigenous people in this region.

So some Indigenous people became Catholic. Not a lot, but some, and soon some of the missionaries were Indigenous.

Part I: Why it’s time Catholics entered the residential school dialogue

As you know, this is a risky topic, especially for Catholics. Some of today’s information might make you mad, might even make you want to throw things at me, so I’m very thankful that we’re on Zoom. I’m also thankful that so many of you care enough about this issue to take time out of your busy schedules to take part. And a special welcome to any Indigenous people that are joining us this evening. We appreciate your presence here.

So let’s dive into the deep of this challenging issue.

As Catholics, we are committed to seeking truth and sharing it in charity, and that is my main goal tonight. So we’ll go through some information regarding the history of residential schools and then we can explore some of the trauma suffered by Indigenous people, and then lastly discuss opportunities for reconciliation.

Another goal for tonight is that we as Catholics work to deepen our empathy for Indigenous people while also growing in respect for the Catholic missionaries that brought the faith to this region.

Why is it important to understand what went wrong in residential schools? Well, historically when we misdiagnose a problem, our proposed solutions rarely work. So in this case if we believe what we’ve heard, if the residential school tragedy was a matter of a good educational system being ruined by bad priests and nuns murdering children, then we can all blame the Church. Simple and done.

However, if the problem is not that, if the residential school system itself was flawed in several key ways, we need to reconsider the conclusions that our culture has arrived at. And if we handle this tragedy wrong, and not in a pastoral manner, we run the risk of judging unfairly and even missing our opportunities to help.

It’s easy at this time to be paralyzed in fear and to be so afraid that we don’t take the chances we should be taking to actually form relationships with Indigenous communities. It’s also very easy to fall into the modern trap of giving ourselves all of five minutes to decide who is good and who is bad in an issue. So a lot of people nowadays – we pick sides, we share some angry posts, and we feel good while actually accomplishing very little. And I really hope that we as a faith community don’t let that happen.

I want to also acknowledge that I am not Indigenous and I don’t claim to speak on behalf of Indigenous people. I am part of a team that’s been blessed to have met with Indigenous leaders and elders, and quite a few residential school survivors, and I will share some of what we have heard from them. But mostly I’m sharing from the things that we have learned, especially over the last five years or so.

The bottom line is I am a Catholic with a message for Catholics, and I know identity politics are very common these days, but tonight I hope we can prove that all Catholics can and should learn more about this issue if we are to make progress.

Several First Nations leaders, including Chief Phil Fontaine, have encouraged all of us to enter the dialogue, so I am doing that tonight. One of our jobs as Catholics is to sincerely hold Church leaders and the lay faithful accountable when their decisions lead to the suffering of innocent people. But one of our jobs, as Canadians, is to fairly hold the government and corporations and our neighbors accountable when their decisions lead to the suffering of innocent people. And in my opinion this is a both/and situation, and I think it’s a disservice to Indigenous people and to Catholics when we oversimplify and misdirect anger and blame.

Some of tonight’s information has come from resources I will share with you throughout, and some has come from historians, researchers, and scientists that we have been collaborating with. Some of this also came from prayer. A while ago after reading some inaccurate media reports I remember telling God – like he needed to hear this from me – most of what people are being told isn’t true. And I sense that what he wants us to know is that while media reports have been inaccurate, most of the hard truths about residential schools have not been told.

So prayer and research and a lot of reading have worked together to deepen my empathy and to reduce my instinct to be defensive. And before we dive into history, I do want to say that the local Church’s response has been well received overall by the First Nations people we have spoken with. Archbishop Michael’s apology and his commitments, combined with your generosity and the goodwill of Indigenous people throughout this region have put us in a position to make real progress on the path to reconciliation.

So please visit our First Nations page at rcav.org/first-nations to learn more about this work and how you can play an important role in it.