Catholic Vancouver May 26, 2022

Religion in Canada isn’t declining quite the way it’s believed to be, Cardus, Angus Reid research finds

By The B.C. Catholic

A five-year study by a non-partisan think tank is complicating the narrative of Canadian religious decline while highlighting the shifting and sometimes complicated nature of Canadian religious identity.

The religiosity of Canadians aged 18 to 35 was one of the surprises identified at a recent presentation of a major Cardus study of Canadian religious identity.

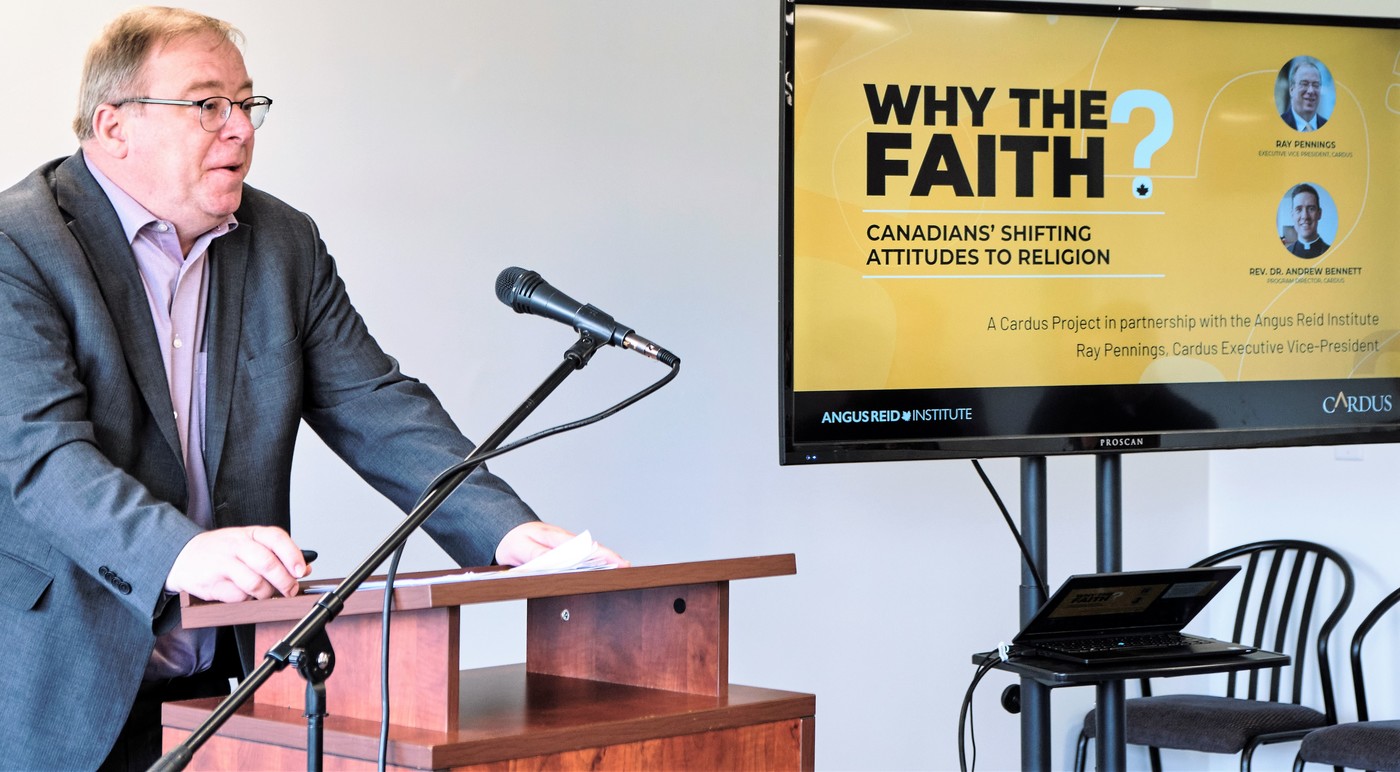

Ray Pennings, executive vice-president of the Canadian think tank Cardus, presented research findings to a gathering at Trinity Western University on Thursday, May 18. About 20 faith leaders and members of local Catholic, Protestant, and Latter-Day Saints communities attended.

The event was one in a national series entitled Why the Faith? At the meetings, Cardus and its research partner the Angus Reid Institute have begun to release the results of their five-year project to local faith communities, which are then invited to offer their own insights and anecdotal responses to the research.

A panel discussion at the event included Father Deacon Andrew Bennett, Director of Cardus Religious Freedom and Faith Community Engagement; David Hunt, B.C. Director and Education Director at Cardus, and J.M. Boyd, president of Glass Canvas.

Pennings told meeting participants that the research grew out of dissatisfaction at Cardus and Angus Reid with the prevailing narrative of declining religiosity in Western countries, and in Canada specifically. Pennings believes the findings will complicate this narrative while providing insight into the shifting nature of Canadian religious identity.

Though he stressed that much of the interpretive work still needs to be done, he said two major trends are undeniable.

First, the data clearly show that people in Canada are still mostly religious.

According to the study, at least 80 per cent of Canadians who identify with a religious faith can be classified as at least minimally religious, ranging from “spiritually uncertain” to “very religious.” This, he said, puts to rest the popular myth that Canadian society is shifting toward complete irreligiosity.

Still, there were some trends he described as worrying. Even though the religious and nonreligious categories are relatively stable across all major religions, Cardus’ data shows a clear trend of people moving from “privately faithful” to “spiritually uncertain.”

The second major trend in the data, according to Pennings, is that demographically Canada is no longer a primarily Christian country and that immigration has become the most important factor in the changing demographics of religion in Canada.

For their part, immigrants to Canada are on average considerably more religious than persons born in Canada and are making up an increasing share of the Canadian population.

Partly because of immigration from predominantly Catholic countries such as the Philippines, Catholics still make up 55 per cent of the religiously affiliated in Canada. Of people raised Catholic, 77 per cent stay in the Church and continue to identify as Catholic later in life.

Among Catholics who leave the Church, 52 per cent say they left for personal reasons, and 27 per cent say they “simply drifted away.”

Across the board, Christians who participate fully in their tradition are the most likely to remain in the faith they were raised in.

Pennings spent considerable time discussing the 18–35 age group because of its distinctive characteristics in Canadian society.

Members of this demographic are more likely than those in any other age group to answer seven religiosity questions entirely yes or entirely no. Relatively few 18–35s were classified as “privately faithful” or “spiritually uncertain.”

Regardless of their religiosity, 18–35s are also the most likely demographic, albeit at only 40 per cent, to believe people should live their religion publicly.

Pennings believes these trends are generally due to 18–35s placing a higher premium than their older counterparts on “authenticity,” holding the conviction that people should live out their identities authentically.

As a whole, the study found Canadians are uncomfortable with public displays of religion. Older Generation X (post-baby boomer) Canadians are the least likely to support public displays of religion.

A comprehensive report on Cardus’ findings is to be published this fall.

How do you measure religious conviction?

Contrary to popular belief, most Canadians profess at least some cultural-religious identity, says Ray Pennings. “No one really checks ‘other,’ he said, referring to the survey option available for the religiously unaffiliated.

As a result, Cardus and Angus Reid Institute encountered some major hurdles when trying to assess whether Canadians are religious.

To differentiate between levels of religious conviction, a set of seven questions was posed, each one relating to a key aspect of an individual’s religious experience or conviction.

- Do you believe in God?

- Do you believe in an afterlife?

- Have you had a religious experience in the last month?

- Is it important to teach children about your religious tradition?

- Do you pray at least once a month?

- Do you read a sacred text at least once a month?

- Do you attend religious service at least once a month?

More specific versions of these questions were asked depending on the declared religious affiliation of the person being surveyed. For example, Catholics would be asked if they went to Mass. For Muslims, whether they read the Quran.

Those who answered yes to all seven questions were classified as “very religious.” Others were described as “privately faithful,” “spiritually uncertain,” or “nonreligious,” depending on how many questions they answered yes to.

Let us know your thoughts about this article. Click here to send a letter to the editor.