Catholic Vancouver March 15, 2022

Moral distress: health workers burning out as high standards meet low system resources

By Terry O'Neill

As one of six spiritual-health practitioners at St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver, Ken Johnson provides spiritual, emotional, and religious support for patients and their families. Part social worker, part psychologist, and part chaplain, the 50-year-old Johnson plays a vital role in fulfilling the Catholic hospital’s commitment to caring for those it serves.

Increasingly during the past two years, Johnson’s services have also been required by hospital staff, as the pressures of working during the COVID-19 pandemic have led to increased emotional strain and exhaustion among doctors, nurses, and other health-care workers.

“Staff have been feeling the stress and the pressure of so many cases, of a heavy workload, and with so much on the line with so many people,” Johnson said. “They’re carrying such a weight.”

Johnson, a Christian who has worked at the Providence Health Care hospital for nine years, said the cause of burnout is sometimes a phenomenon called moral distress.

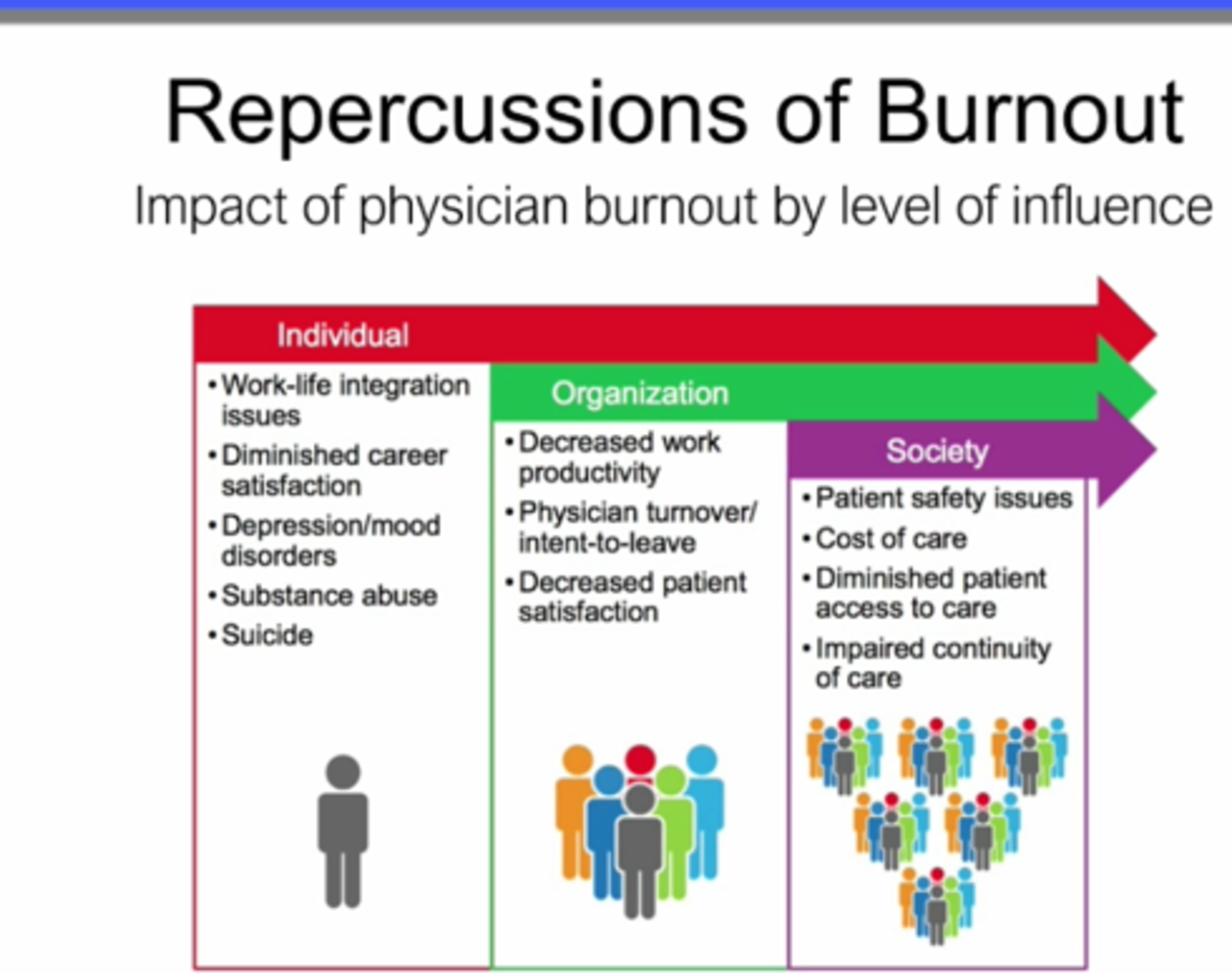

Experts say moral distress is a growing problem that may sometimes more acutely affect workers at faith-based facilities who worry they can’t live up to their high ethical standards. On the other hand, those same institutional values may also provide the resilience and inspiration workers need to cope with and to overcome their moral distress.

A health-care worker in New York City takes a break. (CNS photo/Jeenah Moon, Reuters)

“I think [moral distress] does both things,” Francis Maza, Providence’s newly appointed Vice President of Mission, Ethics, and Spirituality, said in an interview. “It does threaten, and it does call us to do better.”

Moral distress is the profound concern that takes root when a health-care worker knows the correct action to take but is not able to – whether because of governmental regulation, policy protocols, or resource shortages. The conflict may leave the worker feeling involuntarily complicit in an unethical act. A typical circumstance triggering moral distress is the COVID-era policy of preventing families from visiting elderly patients.

First identified among nurses in the 1980s, moral distress is being experienced by health-care workers around the world, regardless of medical system or the religious or secular orientation of the operating authority.

Earlier this month, for example, in describing a critical shortage of intensive-care nurses throughout the province, Aman Grewal, president of the B.C. Nurses’ Union, told reporters, “These nurses are burnt out. They’re morally distressed, and they’re leaving the profession.”

Moral distress was also a featured subject during an online lecture presented March 4 as part of a series sponsored by Providence Health Care, St. Paul’s Foundation, and St. Mark’s College, in partnership with the Archdiocese of Vancouver.

Entitled “Moral Distress, Burnout, Compassion & Resilience,” the lecture featured presentations by Dr. Nadia Khan, head of General Internal Medicine and a Professor of Medicine at the University of B.C., and Dr. Jennifer A. Gibson, director of clinical services and clinical ethicist at Providence Health Care and an adjunct professor in the School of Nursing at UBC.

In opening the event, Archbishop J. Michael Miller said in a recorded message that the theme of this year’s lecture series is Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan. “This, then, is extraordinarily important to our ministry in health care as we navigate these complex and troubling times,” Archbishop Miller said. “The Good Samaritan calls us to work together with all people of good will to build a healthier society – one grounded in solidarity and in justice for all.”

Maza, who moderated the discussion, said in his initial remarks that moral distress and burnout are not new but have worsened over the past few years by natural disasters and the COVID pandemic. Gibson, a registered nurse, chronicled the progression of the pandemic, drawing attention to the restrictions that prevented family-patient contact.

“We use social connections as part of the support system that we strive to have,” she said. But pandemic-thwarting constraints led to workers “being involved in actions that are incongruent with their own value sets,” which in turn created moral distress and burnout.

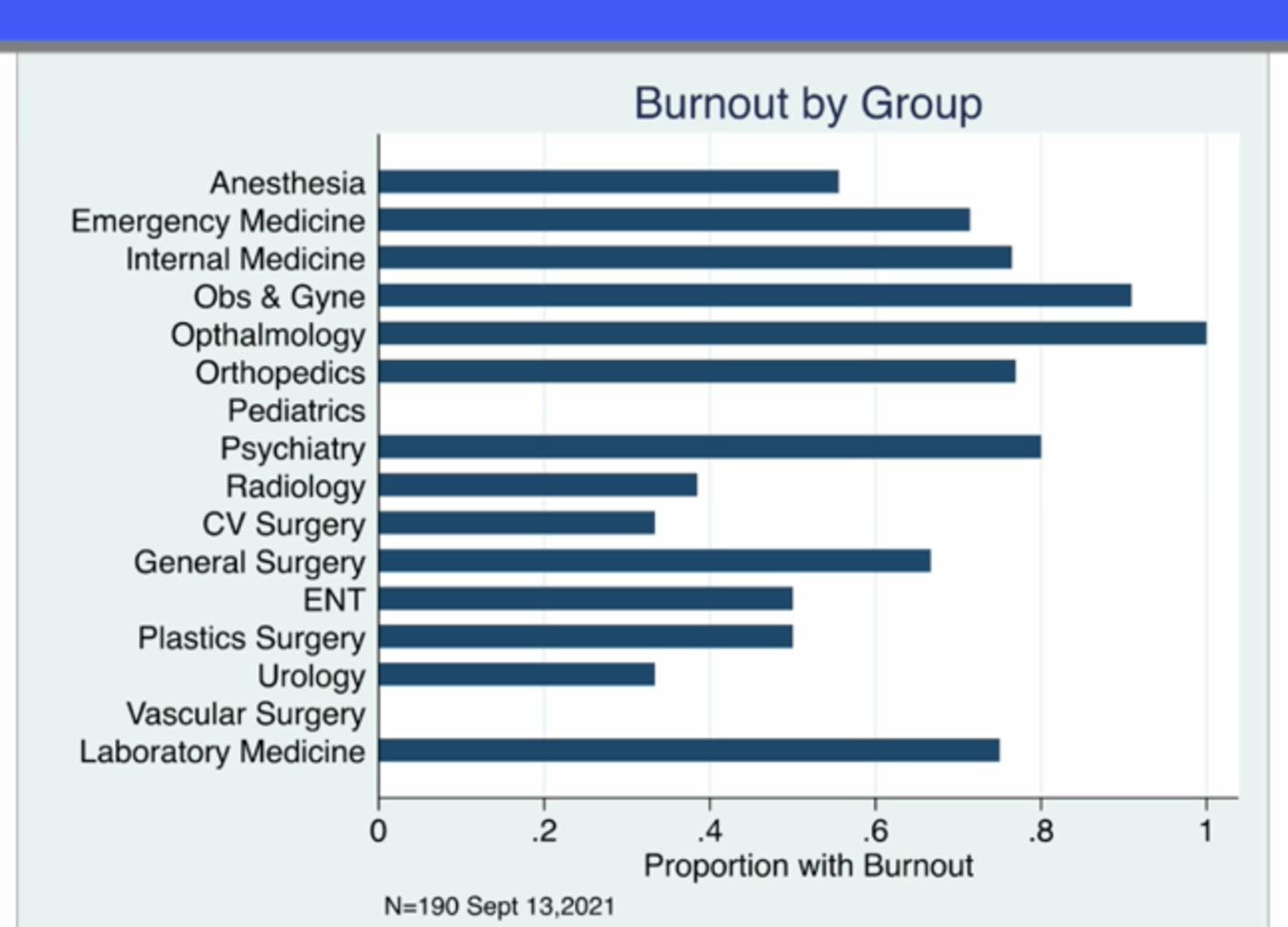

Khan’s presentation centred on the elevated level of burnout among physicians employed by Providence. Prior to the pandemic, burnout was thought to be between 30 and 50 per cent among physicians, she said, but her new survey showed 70 per cent of physicians reported being burned out.

“Moral distress,” she said, “has been shown to be one of the factors leading to physician burnout.”

Elaborating on the issue in a later interview with The B.C. Catholic, she said during the pandemic “you were rationing lifesaving treatments to a degree that you’ve never had to do before.” She told of colleagues from across Canada who faced complex decisions deciding who would be allocated limited intensive-care-unit beds.

In another example, restrictions prevented a patient from inhaling medication in mist form because “aerosolizing” treatments were thought to increase the risk of COVID transmission. “Things that we would automatically do we were not able to do,” Khan said.

Moreover, “the dilemma of not having people come to the bedside [to visit friends and relatives] was also very difficult,” she said. “Everything with the pandemic just became more extreme. It just became an extreme version of everything. And then it prolonged. The intensity increased, and shortages became more exposed, and all of these things are happening for the last two years. And I think that’s added to the distress.”

Even something as simple as a doctor’s inability to spend extra time with a patient can add to distress. “[Spending quality time with a patient] is part of your value system, or your own personal sense of ethics and values,” Khan said, but with so many patients, there’s a corresponding lack of time to spend at bedsides.

She agreed that workers in Catholic hospitals such as those run by Providence may suffer increased moral distress in such circumstances either because of their shared faith-based ethics or because of the effect of the institutions’ high standards. At the same time, however, the institutions’ values may have a bolstering or inspiring effect.

“I think both can be true,” Dr. Khan said. Although Providence does not require workers to be of any faith, “the focus of the day is always on those values of compassion that are a part of religion anyway,” she said.

Unfortunately, she said, “in these COVID times it’s so unprecedented, at the end of the day it would test any healthcare worker regardless of how much support they have either from their spirituality, their family, or their peer support – it could test anyone.”

Dr. Peter Dodek, a professor emeritus of medicine at UBC who worked for 30 years in the intensive-care unit at St. Paul’s, has been studying moral distress among health-care workers for several years.

“It’s a red flag term,” Dodek said in an interview. “It’s the distress that people feel when they are caught between what their conscience tells them to do or not do, and what somebody else, or some external force, is telling them to do or not do.”

His own research shows that moral distress was a serious problem before the start of the pandemic and has remained steady since then. A leading cause is related to issues surrounding end-of-life care. “That is, the nurse knows what really ought to be done for this patient,” but other factors, such as instructions from a superior, prevent that from happening.

“Another cause is [lack of] resources, where the health-care worker knows that we really ought to have a certain type of resource – we’re talking about things that really make a difference – that aren’t provided to patients, and that’s because of system issues.”

“Findings are consistent,” Dodek said. “It’s predominately system issues. It’s usually not an individual’s lack of resilience. It’s not a lack of mindfulness training. It’s not ‘not enough meditation rooms.’”

Moral distress is a genuine problem because it can cause people to withdraw and become sad, angry, and difficult to get along with. It can eventually progress to the point that people leave their jobs.

Dodek cited better resources and improved systems, including better teamwork, as ways to improve not only the health-care workers’ morale but also patient outcomes.

But Khan believes that for moral distress and burnout to be remedied, health-care institutions have to commit themselves to caring for their workers as well as their patients.

“Every system has been built on the premise of looking after the patient,” she said, adding that it’s “a calling and a privilege” to caring for sick people. But if the goal is to create “a very sustainable and optimal healthcare system, we have to look at the workers as well. And I think that is a complete shift for all health-care systems.”

Spiritual-health practitioner Johnson said that when he counsels a hospital worker with moral distress, it helps to remind them that they are the “hands and feet of God” and doing sacred work, rather than focussing on systemic or resource limitations.

“It doesn’t take away what’s missing,” he said. “But it adds to the day-to-day connection with the patient, and the very act of caring becomes a response.”

Johnson said most people employed in health care are drawn to the work because they are “people of the heart.” They may not be religious, but many have a sense of the spiritual and in times of distress respond to his advice about the power of prayer and its ability to bring strength to the patient and encouragement to a staff person.

Through prayer, workers recognize “they are bringing God’s strength to the patient and family.”

From manager to receptionist, moral distress takes its toll on everyone, new ethics head says

When Providence Health Care named Francis Maza as its new Vice President of Mission, Ethics and Spirituality earlier this year, it fittingly selected a man whose doctoral thesis was on the subject of moral distress among health-care workers.

Just two months after his appointment, Maza was the expert moderator of a Providence-sponsored lecture on the very issue of moral distress and one of its primary adverse effects, burnout.

Maza, who replaced Christopher De Bono in the Providence position, said he knew moral distress was an important issue when he began researching its prevalence among nurse managers at long-term care facilities in 2017.

However, his findings took on a new level of importance when the pandemic broke out. “Because of COVID-19, it became more real for so many people and now it seems like all we talk about is moral distress,” he told The Catholic Register in 2020.

Speaking to The B.C. Catholic, Maza said moral distress among health-care workers remains an important issue affecting all health-care institutions and probably affects Catholic hospitals even more severely.

“I would say yes, because we are not in the business of just making money,” Maza said. “Our product or the people we serve are people, and their stories, and their lives. They’re not just some customer. In other health authorities they talk of a customer. I don’t hear that here. I hear ‘patient’ and ‘resident.’ And that humanizes the people that our staff encounter.”

Providence policies also encourage strong connections between patients and their families, who are seen as vital to sick persons’ recovery.

But then COVID came and broke those ties.

“And all of a sudden,” Maza said, “we have a policy that says ‘no, you can’t let them in.’ And we know the impact that it’s causing on the other end.”

Maza saw that impact at all levels, from managers to the person on the intercom who had to tell families not to enter the building. “The level of distress was amazing because it just didn’t make sense [in terms of hospital values].”

On the other hand, Providence’s Catholicity – and its clear values and mission – can support and encourage stressed workers, said Maza, who is Catholic.

In the final analysis, workers in facilities with good internal personnel cultures – where staff are able to voice disagreements and ask questions about procedures – tend to experience lower levels of moral distress, he said.