Catholic Vancouver July 16, 2018

Artist navigates uncharted waters of Indigenous iconography

By Andre Prevost

Detail of the St. Paul icon by Andre Prevost in 2016. The artist worked with Father Garry Laboucane, OMI, to create the icon for St. Paul’s Church in Vancouver. (Photos courtesy Andre Prevost)

Some people have known their path from an early age. Others have sailed

uncharted waters. I am in the second category.

I may not have known where I was headed, but my constant prayer has been for the gift of discernment in every opportunity presenting itself – through something I heard, a news piece that came up, someone entering my life, or a strong urge to speak to someone. This has led to many unexpected turns, but I’ve held to one key piece of advice: “if a door opens unexpectedly, enter it, and give it your best.”

Years ago, I found Eastern icons made a strong impact on me and I started researching iconography. There were no courses available at the time, so I scoured all information I could on the theology and techniques of this sacred art form, learning through trial and error.

But here’s the crux: I was a Latin Rite French Canadian steeping himself in the Byzantine and traditionally Orthodox form. Being very aware of who I was and who I wasn’t, I stayed close to the accepted norms and libraries of the traditional icons.

Opportunities began presenting themselves. I started with a series of icons for St. Edmund’s Church in North Vancouver. My art was appreciated overall, but did meet with a bit of resistance. Some said my icons did not belong in a Catholic Church.

Following a move to Alberta out of necessity, I was led to write a series of icons and murals in a few Ukrainian Catholic Churches. At the time, the fact I am not of Slavic descent was not a concern, given past historic aid from pioneer French Catholic clerics. I was filling a need for these communities.

Then, an influx of Slavic iconographers arrived, taking up my place. It was heartbreaking, but I understood it was a necessary renaissance for the Ukrainian community. Following the closure of this door, I eventually started receiving iconography requests from western Catholic churches once again.

The next uncharted waters in my path were First Nations icons.

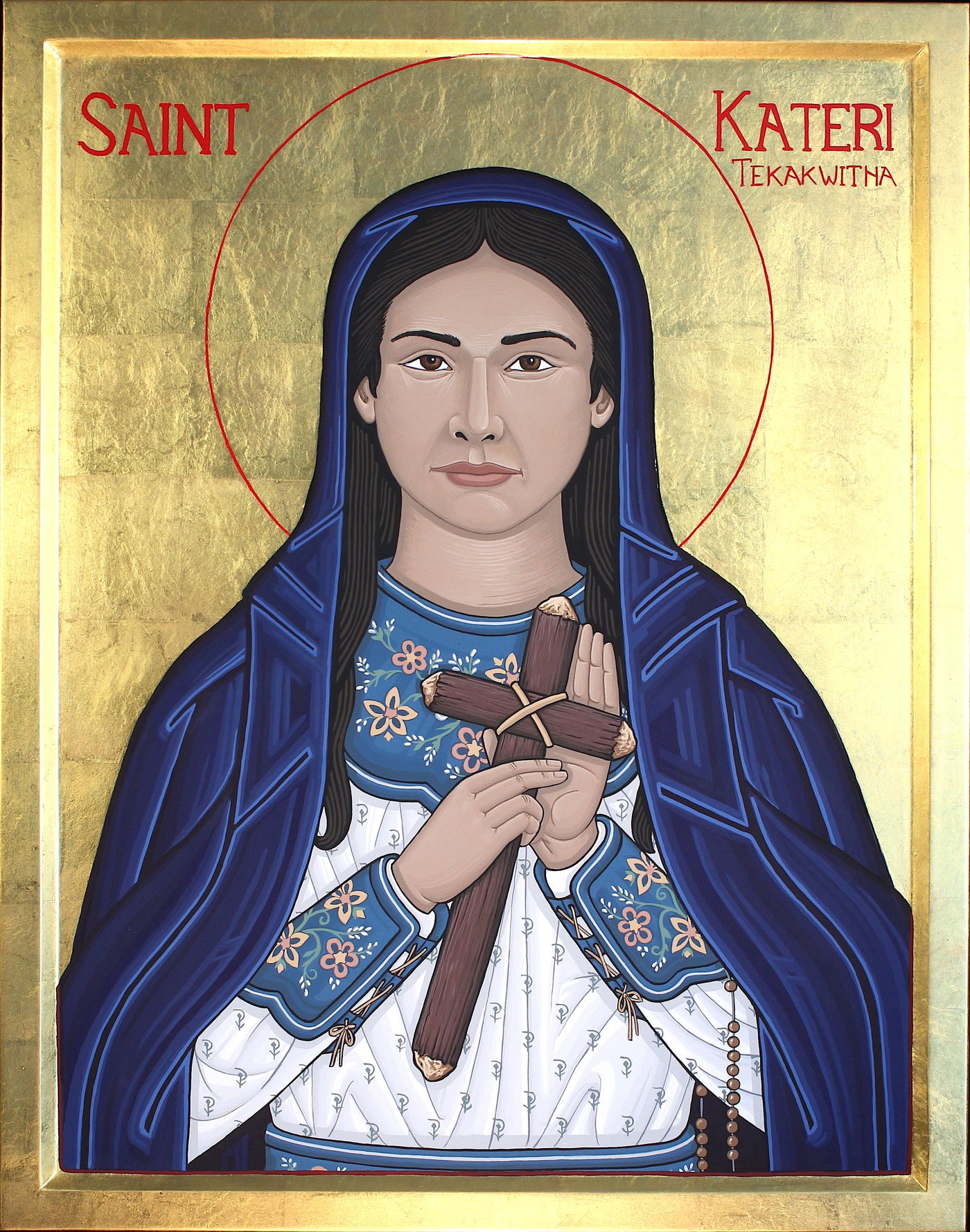

Oblate Father Garry Laboucane, pastor of Sacred Heart Parish in Vancouver, started a conversation around the need for a First Nations icons. I was unsettled at first. He was asking me to open another door, to create a variation on traditional icons while being true to First Nations traditions. I have always had an affinity and deep respect for First Nations cultures, but could I honour them and keep the icons theologically correct and prayerful?

I needed to find a bridge which would give me permission to do this work, inform my journey in keeping the icons true, and allow First Nations peoples to see themselves within. I am deeply grateful to Father Laboucane who understood this; he has been my guide in seeing traditional Christian imagery through First Nations eyes and spirituality.

The first icon was of St. Paul, set within a West Coast Cultural imagery. It represents Paul as a Coast Salish teacher or messenger, so the Coast Salish and Indigenous Peoples can see themselves as bearers of the Good News and as having a shared experience of St. Paul.

The icon is strongly set within numerous symbols: a talking stick, a canoe set for another voyage, a cedar hat, and a cedar bough and parchment with the inscription: “Follow Him and let your roots grow deep into Him.” (Col. 2:6-7)

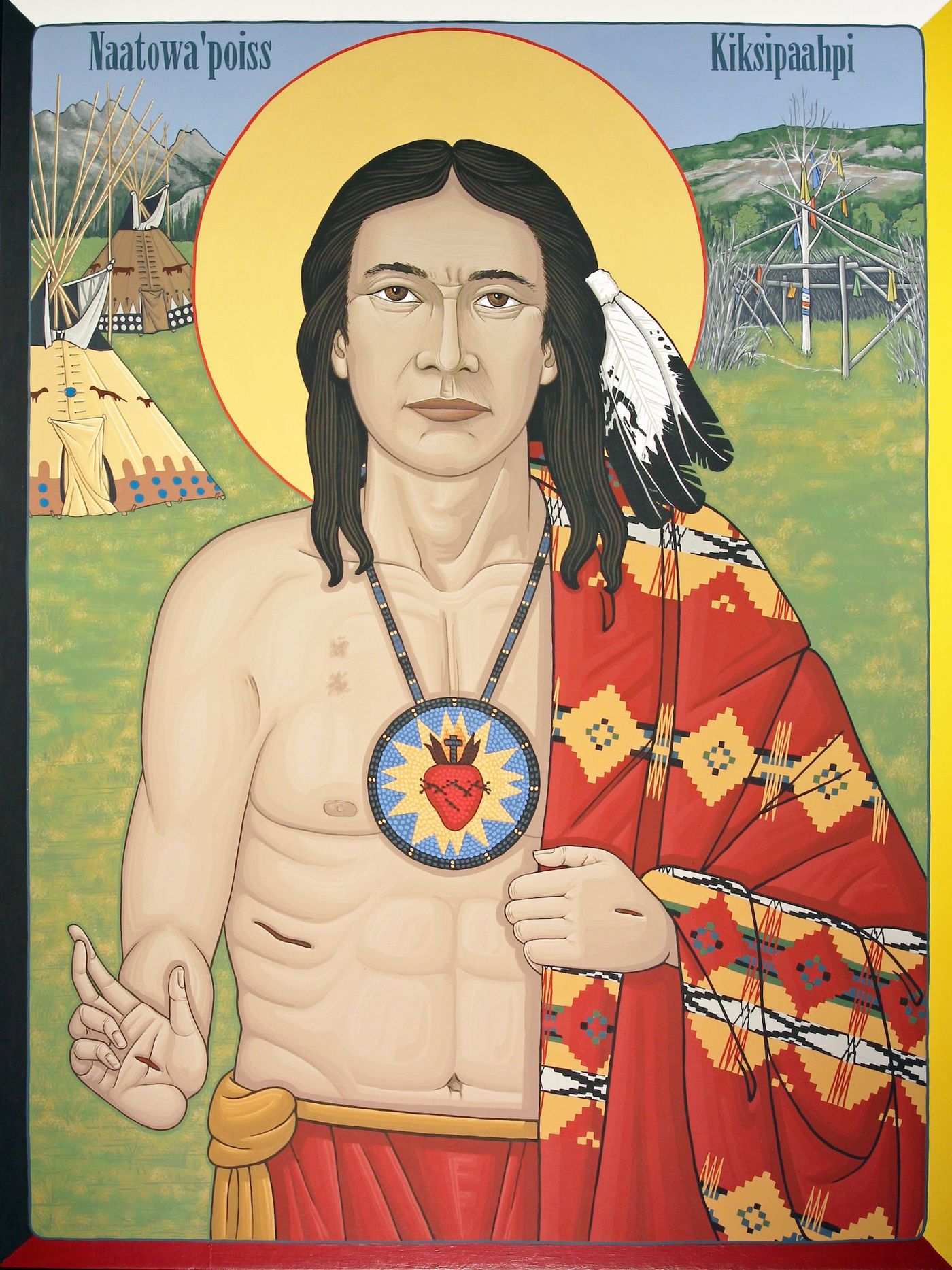

Another icon I completed was of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, in collaboration with Romeo Crow Chief of the Siksika Nation. It portrayed Jesus as a Blackfoot man and set him in the context of the Sundance, requiring me to find a bridge between theology and First Nations traditions.

The Sundance has a long preparatory period before a candidate is deemed ready, which brings to mind Christ’s 40 days in the desert. The critical element of the Sundance is that it is a personal sacrifice on behalf of the community, and a lifelong commitment to service.

In my research, I came across a 2014 article by John Woodward where he wrote: “How important is it that the Lakota people know that Jesus is for them and to understand that he did suffer in his incarnate body in a way that Lakota people can relate to?” The article was about the Lakota, but still so pertinent for the Blackfoot, and for all First Nations.

The icon includes the Sundance and the Pascal sacrifice as two separate events, showing the Sundance scars on Jesus’ chest and the marks of crucifixion on his hands. Its setting depicts a camp of tepees with Siksika designs, a Sundance structure, and Christ wearing a pendant from the Crow Chief family and Plains eagle feathers the same way Chief Crowfoot wore his.

The most recent First Nations icon I’ve written is the

Siksika Immaculate Heart of Mary. It was designed as a pair to the first Sacred

Heart icon and presents Mary in Siksika regalia with the traditional heart symbol

used in Latin Rite images depicted as a beaded pendant.

The setting behind her has the same tepee configuration as the Sacred Heart icon, but is situated near the Bow River and Castle Mountain in Alberta, which is of historical importance to the Blackfoot People.

A journey in uncharted territory can be stressful, especially when supporting a family, but being open is essential in finding yourself where you are needed and when.

My overall body of work in iconography has been varied and at times eclectic. Some don’t approve of my use of modern acrylic paint versus traditional egg tempera. Some will not understand my recent series of First Nations icons. But it is a journey of faith, a journey of trust, and a journey of love.

I’ve learned, through years of persevering, that I will never be in a particular niche. For some, I am too Orthodox/Byzantine, for others not Byzantine enough. I will always be that fellow who can never be Slavic, Greek, or Indigenous. But so long as I keep true to my sincerity of heart, my faith in God, and due diligence in research for every icon, I am on the right path. I know that the Spirit will guide. It may not be a path of financial stability, but the right path nonetheless. I am humbled that God wills to use my hands in his icons.

It is an exercise of humility, not ego, to recognize that an icon is deeply a part of the prayer and lives of so many people. That is one thing an iconographer will never know the extent of. In that moment between a soul in prayer with God and the icon, the iconographer has no place.

Andre Prevost has been writing icons for more than 35 years and his work appears in churches and private homes across Canada. This article is reprinted with permission.