Catholic Vancouver December 14, 2022

Acclaimed residential school history gets second printing thanks to reconciliation funding

By Terry O'Neill

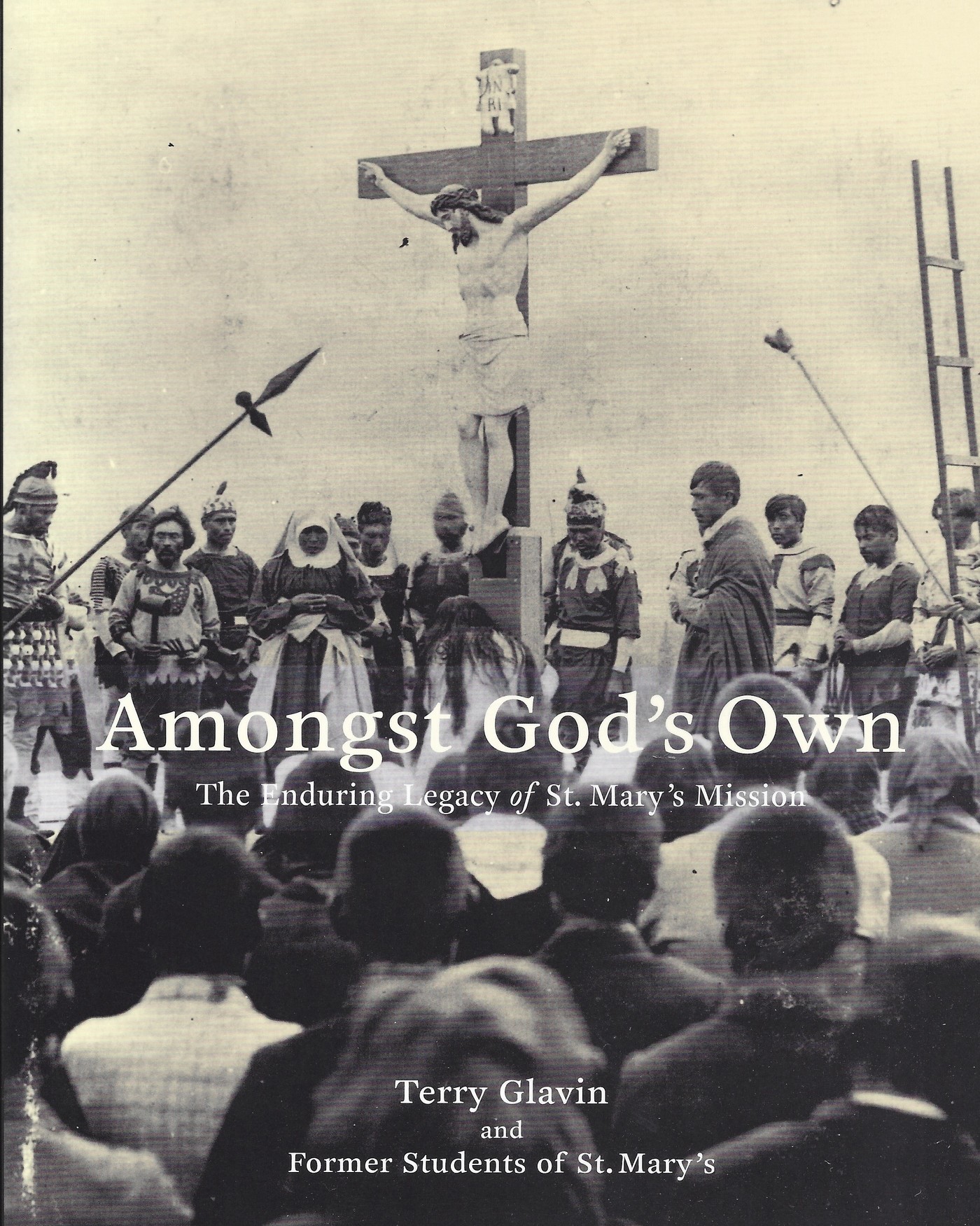

Amongst God’s Own, an acclaimed out-of-print Indigenous-led history of St. Mary’s Indian Residential School in Mission, will get a new lease on life thanks to the national Indigenous Reconciliation Fund, which will pay for a reprinting of the book.

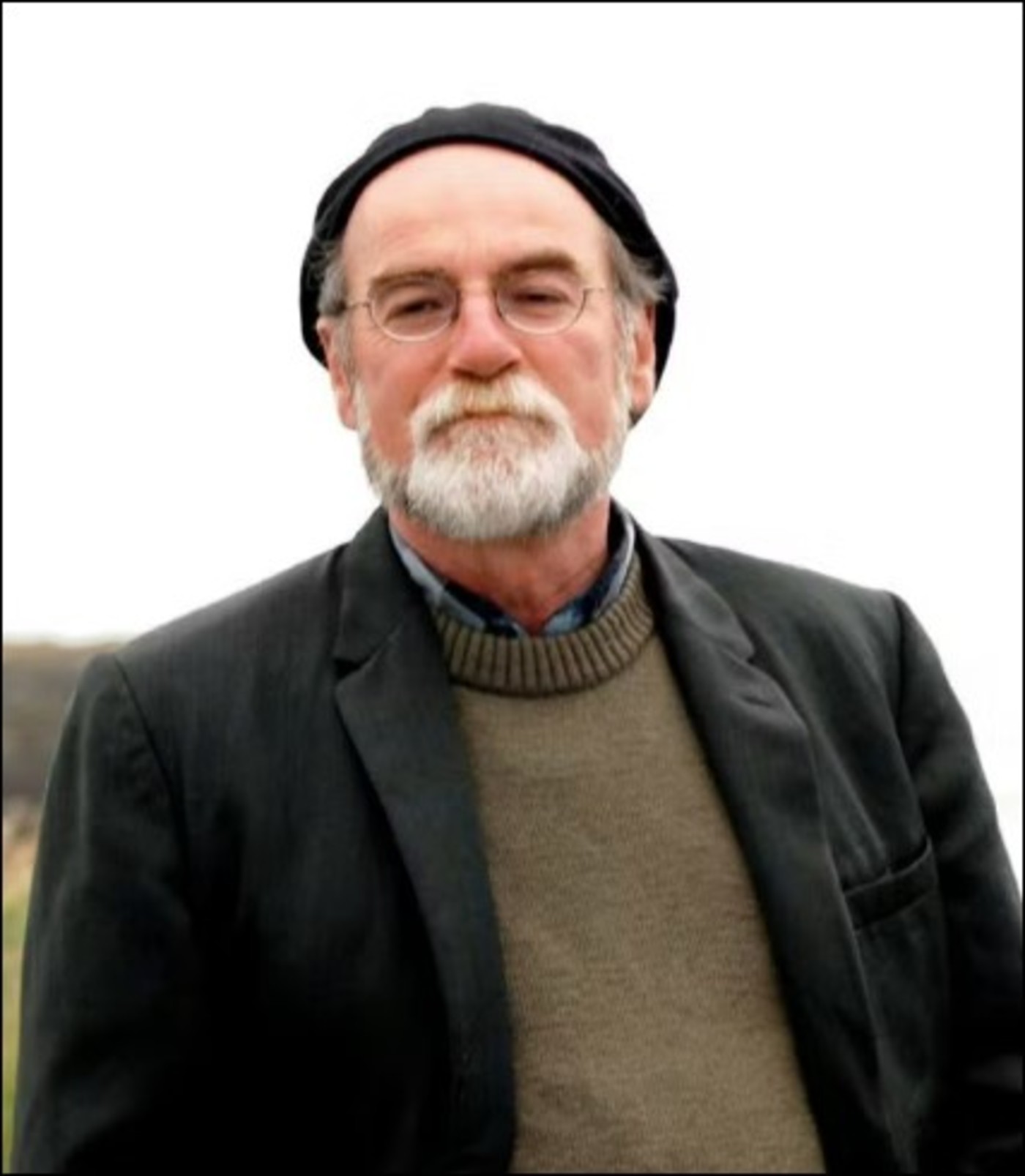

The national Indigenous Reconciliation Fund is awarding the Fraser Valley Coqualeetza Cultural Education Centre a $54,225 grant so it can update, reprint, and distribute the innovative, Indigenous-led St. Mary’s history by B.C. writer Terry Glavin.

In supporting the reprinting of an important history book, the Archdiocese of Vancouver is making history of its own, as the grant will be the first of what promises to be an ongoing series of local awards from the national fund.

The archdiocese held special collections during the past two Septembers to seed its part of the fund.

Directors of the national fund announced in July that $4.6 million had been collected from dioceses across the country as part of a nationwide commitment to raise $30 million over the next five years.

The Coqualeetza Cultural Education Centre will use the grant to allow Longhouse Publishing to revise and reprint Amongst God’s Own: The Enduring Legacy of St. Mary’s Mission , which Longhouse first published in 2002. An archdiocesan committee approved the grant application before submitting it to the national board for approval. The exact amount of the grant has not yet been made public.

Reviewers of the book praised author Terry Glavin for giving voice to 35 former students, most of whom attended the school in the 1940s and ’50s, and for presenting a comprehensive, balanced, and revealing portrait of an Indian residential school, a portrait that was neither entirely negative nor entirely positive. (See Voices sidebar)

“I don’t think any of the histories that have been written about the residential schools so far tell the whole story. There is no balance,” Bill Williams, a former St. Mary’s student, wrote in the book’s foreword. “But in Glavin’s work, it is there. I feel it is very important to get this point of view across.” Williams himself wrote that his experiences were mainly positive.

The Mission Indian Friendship Centre, which Williams managed, commissioned the original book after receiving funding from the Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

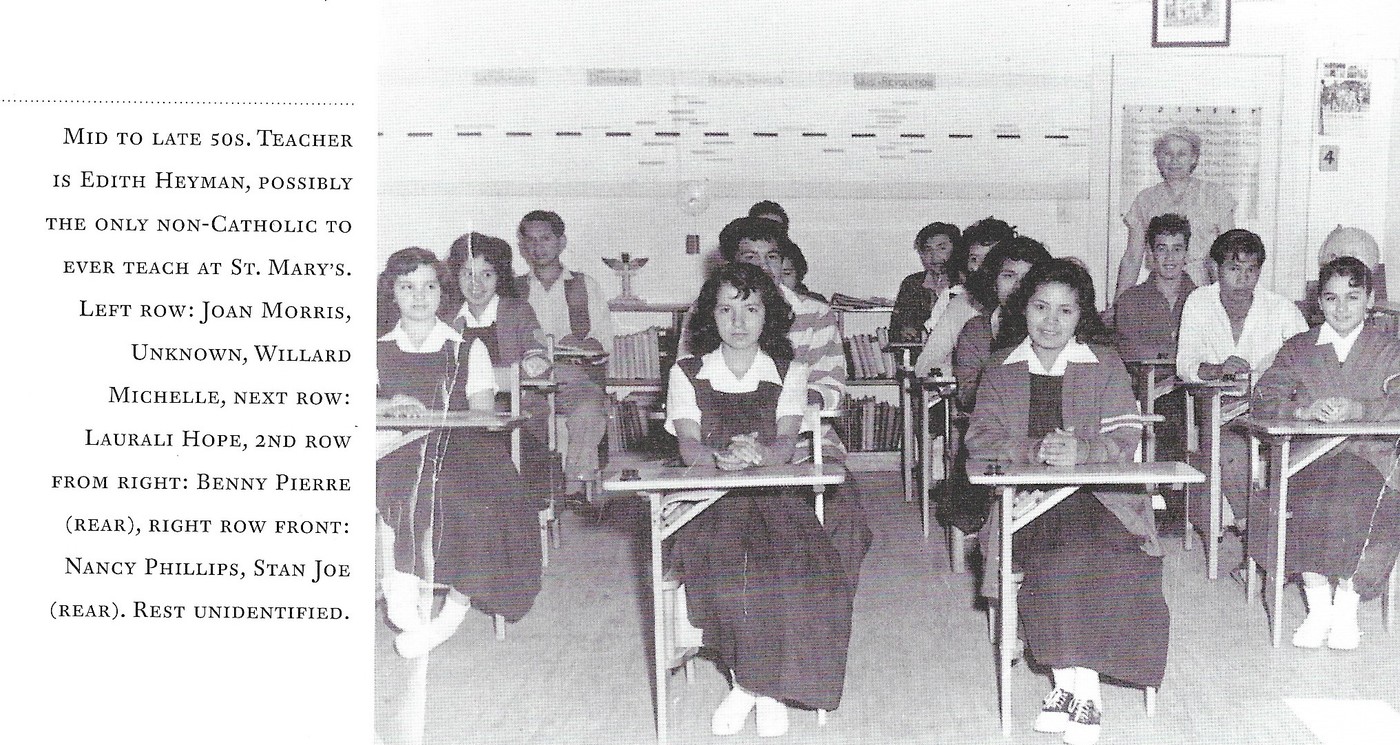

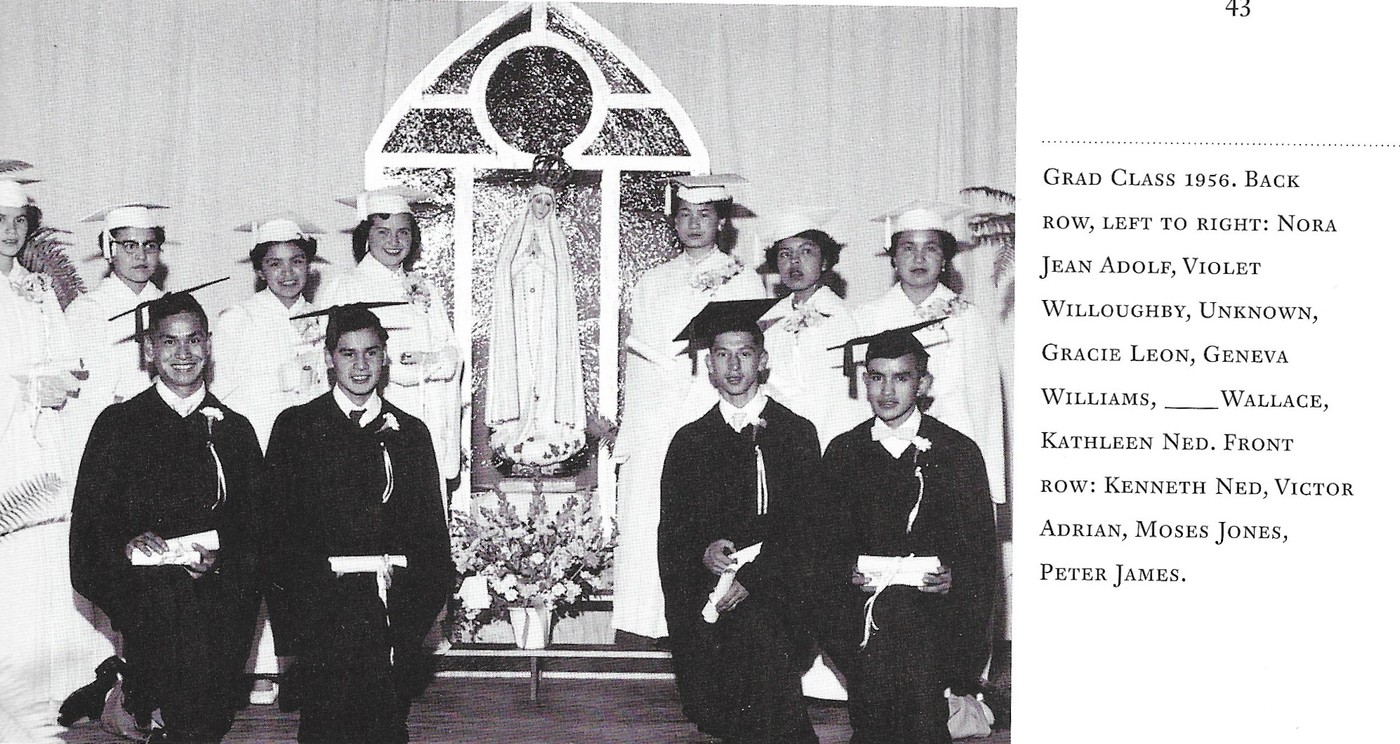

The new edition of the book will be retitled St. Mary’s: The Legacy of an Indian Residential School. It will include some new content, including photographs recently made public by the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, which operated the school from the time of its establishment in 1863 to its closing in 1984.

James Borkowski, Archbishop J. Michael Miller’s Delegate for Operations, said in an interview with The B.C. Catholic that he expects the book to have at least two immediate positive impacts. “The first is that a very important local Indigenous community will know that they were heard and seen and that their stories will live on,” Borkowski said.

“I think the second impact will be that every Catholic church and every Catholic school in this province will receive copies. The Indigenous people that we’ve been working with have wanted to know that Catholics are interested in becoming more educated about what really happened at these [residential] schools.”

Borkowski noted that, in supporting the grant to allow the reprinting and distribution of the book, the archdiocese was responding to several Indigenous elders who wrote letters of support of the effort, saying they did not want this history to be lost.

“So the elders and the survivors themselves have asked us to republish this book, and out of respect for these authentic stories from actual people who experienced residential school we want to honour their request,” Borkowski said.

While promoting the special collection in September, Archbishop Miller noted Pope Francis’ visit to Canada in July “to deliver a sincere apology to Indigenous people for the role Catholics played in a deeply flawed Residential School System. When we are able to set aside any defensiveness, we can truly see the harm caused by systems that resulted in abuse, the separation of children from families, and the subsequent loss of culture and tradition.”

Through the new grants, he said, “we are investing in Indigenous-led projects that contribute to healing, education, and the steps needed for true reconciliation.”

Author Glavin said in an interview he recognizes that, in giving voice to former students whose experiences were varied, his book does not align with the prevailing narrative that everyone who attended an Indian Residential Schools had only terrible experiences.

His more nuanced account was not meant to condone the residential-school system, he said, but only to give legitimate voice to those Indigenous men and women who felt their voices were not being heard. “I think we should be able to have some sort of conversation about this,” Glavin said. “This is an important chapter in Canadian history, after all.”

He pointed out that while some students had “utterly horrific” experiences, others’ encounters were “utterly benign and even delightful” and the two groups “did not dispute one another’s stories.”

Glavin said his concern has long been “that we not force upon [the former students] a narrative paradigm that either dismisses residential schools in their entirely as an abominable genocidal project, or upholds the residential schools as some sort of benign civilizing mission. Just let people talk, for God’s sake. Let Indigenous people tell their own stories.”

Aboriginal elder Philomena Fraser, 84, agrees with the importance of letting the former students tell their stories. Fraser, who collected the narratives that Glavin used in his book, said in an interview that the book captures the actual, authentic words of those who were at St. Mary’s.

“And even in my own recording with the participants, I was amazed of some of the things they had gone through, even though I was there for seven years, she said. “And I told people I must have had my head in the sand like an ostrich, and I never noticed anything. I think things like that were just never spoken about.”

Many of the troubling stories involved corporal punishment, rigid discipline, and the prohibition on speaking one’s Native language. “There were some good stories [too], there’s no doubt about that,” Fraser said. These most often involved the kindness of teachers as well as academic and sports-related accomplishments. (See sidebar, page xxx)

Observers have pointed out that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission itself, in its 244-page “The Survivors Speak” report, included a four-page section entitled “Warm memories.” As well, the commission’s “Missing Children and Unmarked Burials” report notes, “Many students had positive memories of their experience of residential schools and acknowledge the skills they acquired, the beneficial aspects of the recreational and sporting activities in which they engaged, and the friendships they made.”

Similarly, writing in The Calgary Herald before the reports of Truth and Reconciliation Commission were made public, Murray Sinclair, the commission’s chair, said, “While the TRC heard many experiences of unspeakable abuse, we have been heartened by testimonies which affirm the dedication and compassion of committed educators who sought to nurture the children in their care. These experiences must also be heard.”

Recognition of the varying voices should not lead observers to conclude that the Church is attempting to avoid responsibility for the many wrongs it committed while running the schools, Borkowski said.

“I think we are going out of our way to make sure that Catholics are not excused,” he said. “In fact, there are multiple heartbreaking stories [in Glavin’s book] about the roles that Catholics played in destroying lives of some former residential students. And, perhaps more important, we are leaving the stories for Indigenous people to tell. And while some had entirely different experiences, those are their stories, and whether they are uplifting or heartbreaking, it’s equally important to us that they be heard.”

In a short note about St. Mary’s, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission reported that a former school employee was convicted in 2004 of 12 counts of indecent assault in relation to his time at the school and was sentenced to three years in prison.

This past August, the Sto:lo Research and Resource Management Centre began work to locate any unmarked graves where St. Mary’s was located. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission listed 12 students who died at the school over its 121-year life.

Reviews: ‘So that’s what it was really like’

In describing Amongst God’s Own, the U.S. Library of Congress’s online research guide on the Indigenous peoples of Canada relates how the book employs “Native voices” to recount the realities of day-to-day life at St. Mary’s Indian Residential School.

“Moving beyond the prevalent discourse of oppression and victimhood,” the guide’s bibliography states, “the result is a ground-breaking portrait of this place and time that illuminates 200 years of Native-white interaction in BC.”

Canadians who reviewed the book when it was originally published 20 years ago similarly noted the balanced picture it painted of residential school life. Here is a selection of excerpts of those reviews, provided by Ann Mohs, owner of Longhouse Publishing.

“At first glance, one might assume this is another negative account of what the priests and nuns did to the Aboriginal students. But this book gives voice to a different perspective ... The great thing about this book is that the personal narratives are varied and offer a balance that is rarely shown. Of course, many abuses did occur and that is a large part of why such books are written – to help in the healing process.” — Marilyn Aldworth, District Librarian, SD 44 (North Vancouver), in The Bookmark.

“This is an amazing book ... author Terry Glavin is to be commended for the balance, fairness, candour, and accuracy of the reports. The book, with its many photographs, is a poignant record of local and Canadian history. Its stories are unforgettable.”

— Paul Matthew St. Pierre, Voices and Visions, The B.C. Catholic.

“Trial lawyers handling residential school abuse cases will find this a balanced and useful book. The author has drawn on 35 now elders for narrative accounts of their experiences. The book is much enriched by the loan of many historical photographs.”

— Ronald F. MacIsaac, MacIsaac & MacIsaac law firm, Victoria, Book Reviews, The Verdict

“Glavin neither minimizes what was wrong with residential schools nor does he vilify everyone who worked within that system. A perusal of his book is very much like reading the juicy bits in private diaries. The reader comes away with a feeling of ‘so that’s what it was really like.’” — Joan Taillon, Raven’s Eye.

Voices of St. Mary’s: ‘An evil place, a beautiful place

In his introduction to Amongst God’s Own, author Terry Glavin writes that the complex story he discovered in writing about the varied experiences of First Nations people who attended St. Mary’s Indian Residential School in Mission was different than the single story about residential schools that was dominating the public narrative at the time – and still dominates it today.

“This book is about a terrible story,” Glavin writes in the 2002 introduction. “It is a story that involves great suffering, betrayal, love, sacrifice, loss, and redemption. This book is also about a wonderful story, a story that involves faith, memory, comfort, forgiveness, sorrow, and loyalty.” Of St. Mary’s, he concludes: “It was an evil place. It was a beautiful place.”

The diversity and range of students’ experiences is reflected in excerpts from some of the recollections of the 35 men and women whose testimonies form the heart of the book:

Mary Ann Roberts (attended St. Mary’s from 1946 - 1957)

“The fear that they instilled in us was not right. Mind you, they weren’t all bad. Some of them were nice, but it just takes one or two ... I guess with a school like that a lot of the memories that we have that stand out are unpleasant, and I didn’t have any physical or sexual abuse, but a lot of things that were against a school like that would be mentally the way that they made you feel.”

Marie Ganzeveld, (1946 - 1958, orphan raised by the Sisters of Saint Ann)

“The sisters were very good to me. I remember spending a Christmas with them and I received a beautiful doll with ringlets.”

Martina Pierre (1950- 1964)

“We learned that everything was a sin. Especially bad were the beliefs that our people practised. It was known as witchcraft ... I felt like a lost person not worthy of the White man’s God that they preached about.”

Laura Thevarge (1946-1948)

“I didn’t really get the negativity that other people said happened at residential schools ... To me, the brothers, sisters, nuns, and priests treated us fine, at least as far as I could see.”

Grace Bobb(1941-1943, 1944-1956)

“Discipline was quite regimented at first but when you’re all doing the same thing it seemed normal. We were disciplined daily, and it stuck with me all my life. I’m very efficient at work and always on time. It was good for me. The worst thing I ever saw in school was the strap which, thank God, I never got.”

Wayne Florence (1954-1955)

“They were pretty cruel. They’d bat you on the back of the head and I guess at first start, getting up in the morning and make you have a shower in cold water and wash your head in cold water ... [One of the nuns] I think was the worst one of the bunch. She ripped half my ear off at one point because I wouldn’t listen to her ... I’m half deaf now.”

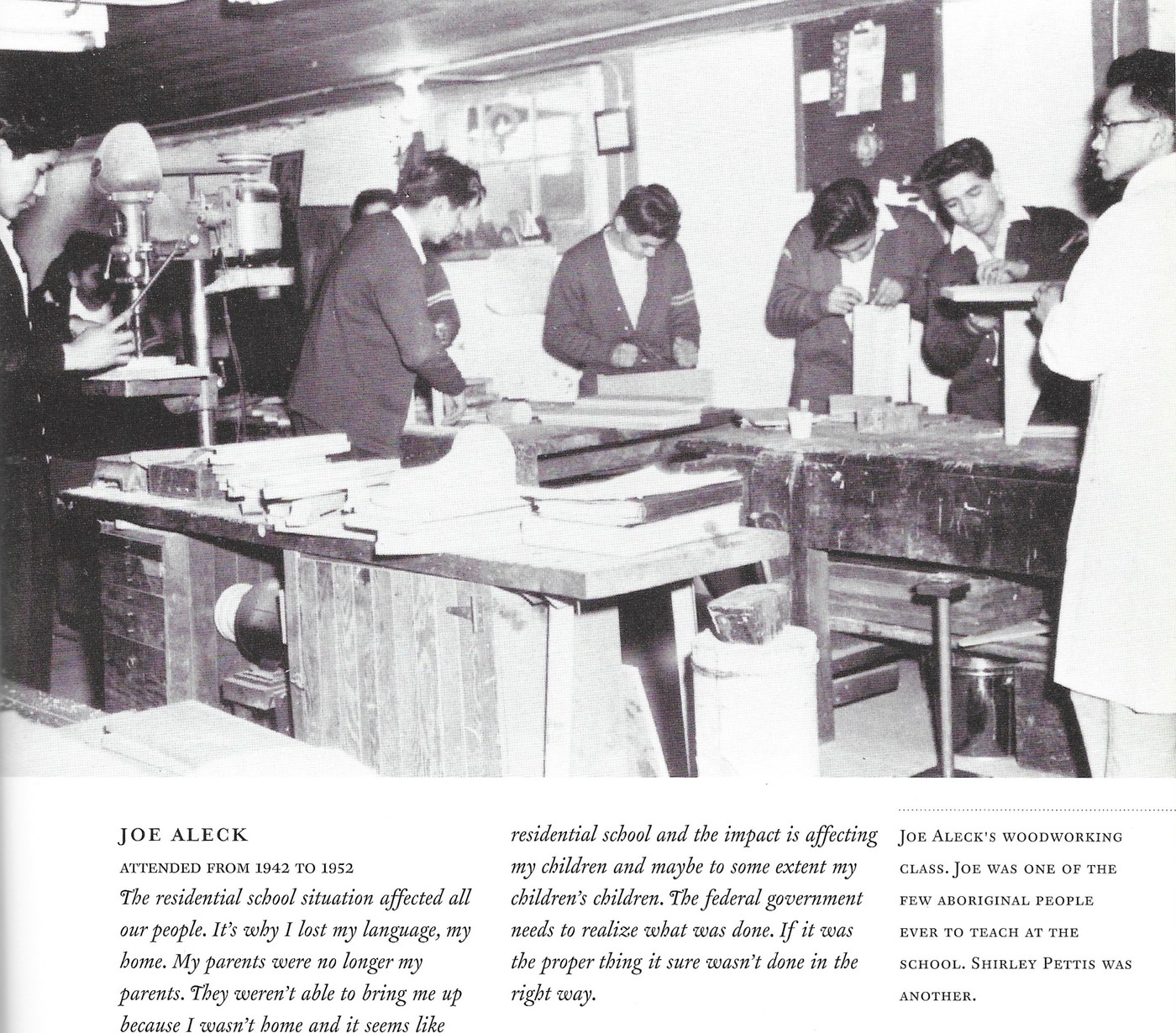

Joe Aleck (1942-1952)

“The residential school situation affected all our people. It’s why I lost my language, my home. My parents were no longer my parents. They weren’t able to bring me up because I wasn’t home and it seems like I lost my ties for a while. I think the emotional and mental impact was the greatest on all our people and it’s going to take a long time to bring people back to normal.”

Mary Lou Sepass (1937-1948)

“I have no regrets going to school at St. Mary’s. In fact, I feel very fortunate. Not only did I learn academics and domestic chores, I met many people [who] became a part of my life. I think of the awesome works of the priests and nuns that played a big part in my life. To them I will always be grateful. St. Mary’s, to me, is a good memory, a good school.”

Click here to send us a letter to the editor about this or any other article.