Voices September 15, 2017

Conversion coincides with vision of shattered pride

By C.S. Morrissey – Global Theatre

“Curiously, my conversion had made me sensitive to music,” remarked French Catholic thinker René Girard, recalling his conversion experience which unfolded over the winter of 1958–1959.

“What little musical knowledge I have, about opera in particular, dates from that period. Oddly enough, The Marriage of Figaro is, for me, the most mystical of all music. That, and Gregorian chant,” said Girard.

Girard’s biographer Cynthia L. Haven observes Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro “has perhaps the most exquisite portrayal of forgiveness in the entire opera canon, when the Countess’ merciful Più docile io sono opens out to a sublime ensemble” (in Act IV, Scene XIV).

Haven draws a connection between this work of beauty by Mozart and Girard’s life’s work, surmising it was “no coincidence that forgiveness was to become a theme in Girard’s writings for the rest of his life.”

After all, Girard concluded his famous book The Scapegoat by writing, “The time has come for us to forgive one another. If we wait any longer there will not be time enough.”

Wiseblood Books recently published Haven’s account of Girard’s conversion experience in a handsome little chapbook, ‘Everything Came to Me at Once’: The Intellectual Vision of René Girard.

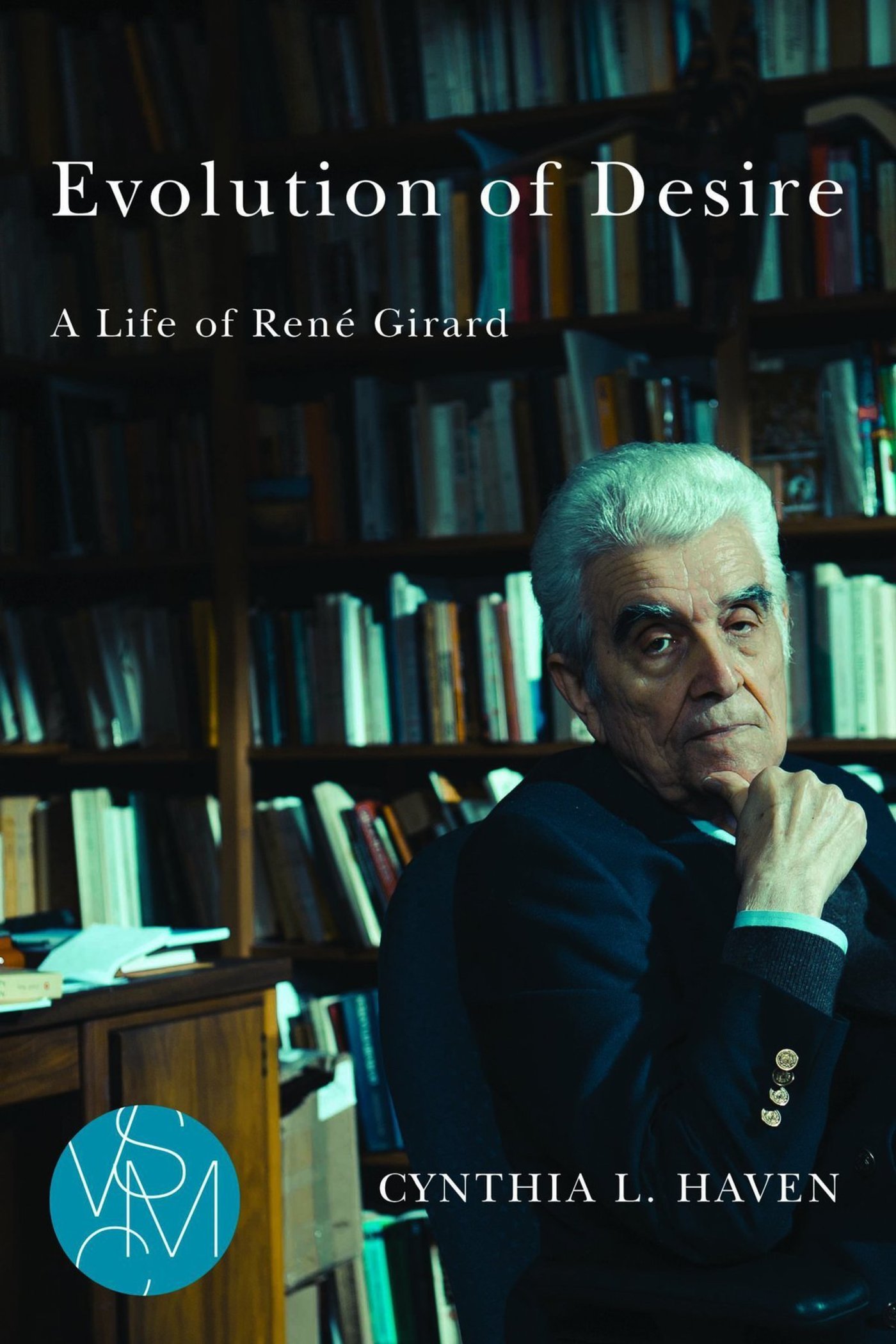

The story of Girard’s conversion in the Wiseblood volume provides us with small preview of Haven’s forthcoming complete biography of Girard, Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard (from Michigan State University Press, in early 2018).

Her discussion of Girard’s conversion emphasizes the theme of “intellectual vision,” in which a comprehensive insight envelops a thinker. In Girard’s case, the experience of such an intellectual vision nourished a conversion that culminated in his finally becoming a practicing Catholic in 1959.

The grand theme of forgiveness fits organically with Girard’s innovative analyses of human behaviour.

The grand theme of forgiveness fits organically with Girard’s innovative analyses of human behaviour. During the time of his conversion, Girard was thinking about the novels he was teaching to his students as a university professor.

It was the time when he was writing his first book, Deceit, Desire, and the Novel: Self and Other in Literary Structure. Because of his conversion experience, he found he was finally able to write the conclusion to the book. He was also compelled to rewrite other parts of the book, in order to bring it in line with his intellectual vision.

Girard’s book argues the

greatest novelists underwent a kind of religious conversion when they

themselves finally discovered how their great novels had to end. Before the conversion happens, the novelist’s

first draft is usually only a mundane “attempt at self-justification,” said

Girard.

But a great novelist eventually discovers self-justification at the expense of others “will not stand self-examination.” The novelist then experiences an “existential downfall,” which is “shattering to the vanity and pride of the writer,” explained Girard.

“Once the writer experiences this collapse and a new perspective, he can go back to the beginning and rewrite the work from the point of view of this downfall. The novel is no longer self-justification.” In his first book, Girard thus showed how “the career of a great novelist is dependent upon a conversion.”

Girard’s own conversion was contemporaneous with his intellectual vision of how great novelists used the fruits of their own self-examination.

Girard’s own conversion was contemporaneous with his intellectual vision of how great novelists used the fruits of their own self-examination. He realized they unsentimentally analyzed the patterns of human desire, in which people imitate each other and become rivals.

In an interview book, Reading the Bible with René Girard (edited by Michael Hardin), Girard made an interesting point about how his theory of desire must also be a theory of history.

“Competition is the essence of our world; competition is essentially mimetic. So in a way the story of mimetic desire is a historical one: it’s the story of the evolution of desire in the Western world,” he said.

Perhaps for this reason Haven has titled her biography Evolution of Desire.

“This historical aspect is one of the main points of my first book,” observed Girard. “It’s a very different book from normal literary criticism, because what is hinted at is a history of the Western world consisting of rivalrous relationships.”

In another interview book, Evolution and Conversion, Girard concludes, “We will always be mimetic, but we do not have to engage automatically in mimetic rivalries. We do not have to accuse our neighbour; we can learn to forgive instead.”

No wonder Bishop Robert Barron writes that Haven’s “account of his conversion, as well as his academic work, supports my claim that in centuries to come René Girard may be remembered as one of the great Fathers of the Church.”