Catholic Vancouver June 25, 2019

Plastic out, pasta in: Straw-Ghetti, mugs part of green dividend

By Agnieszka Ruck

Owners of a start-up company in Coquitlam have discovered cutting down on plastic isn’t just good for the environment; it can directly help the poor and homeless, too.

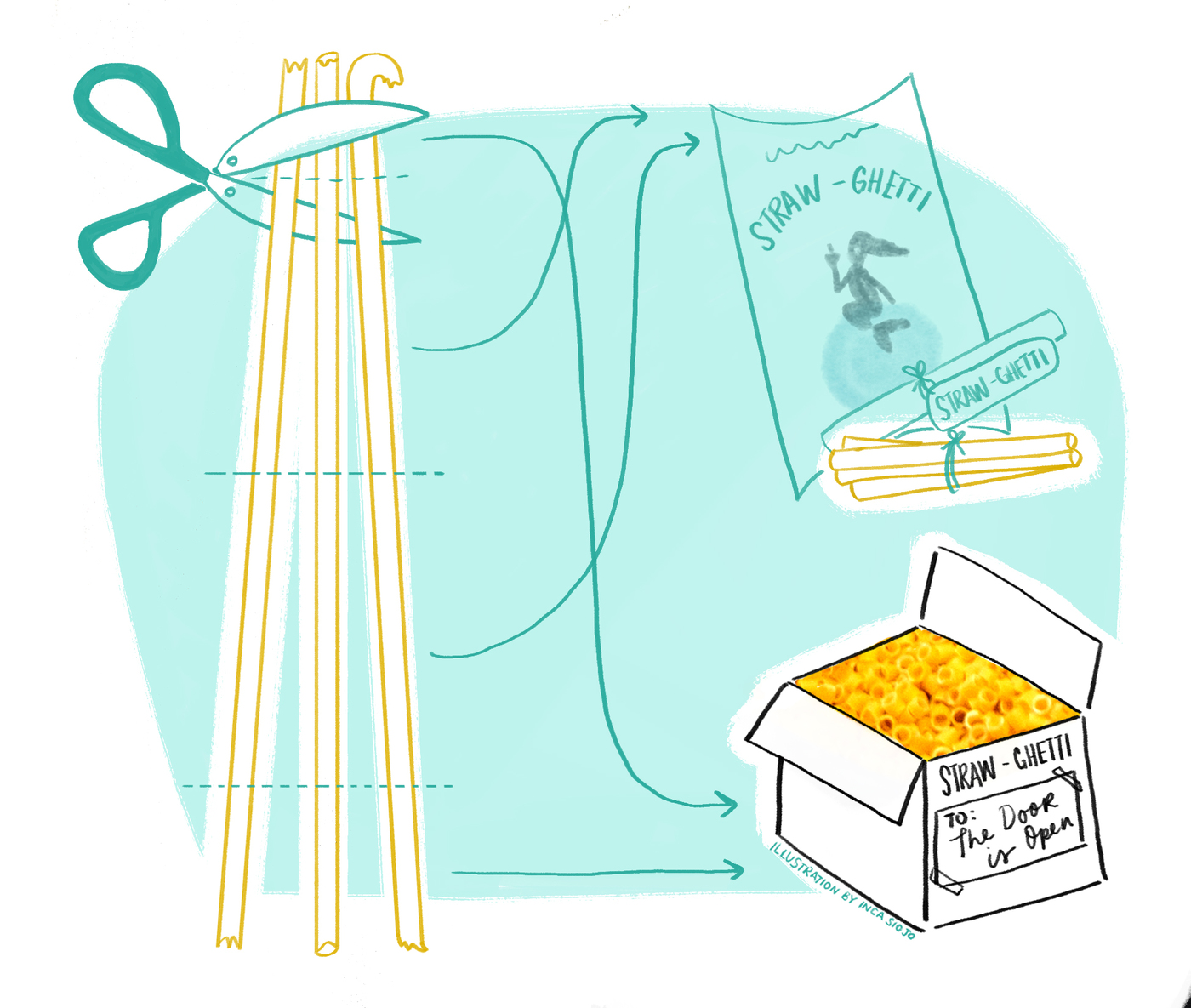

Vanessa Brascia and Cory Melville officially opened Straw-Ghetti in February. Their company imports Italian pasta, cuts it to size, and sells it as an eco-friendly substitute for plastic straws. The pasta leaves no residue and lasts longer in a drink than other plastic straw alternatives.

But cutting raw pasta down to cocktail or regular straw sizes results in a lot of waste. Over the last several months, they have packaged hundreds of thousands of straws, resulting in about 100 pounds of awkwardly shaped pieces of pasta. They ate some and gave more away to friends and family, but were still left with more than 50 pounds of uncooked Italian goodness.

Deciding to donate the leftover pasta, they were quickly connected to The Door is Open, the Archdiocese of Vancouver’s drop-in centre for the poor and homeless in the Downtown Eastside.

Feeding the hungry

The pasta “will definitely go into use,” said Frances Cabahug, co-manager at The Door is Open. Her organization serves approximately 250 servings of hot food every day, 365 days a year. These daily free lunches usually include a sandwich and a soup, and the soup almost always contains pasta.

The Door is Open often receives donations of vegetables or bread, but Brascia and Melville’s delivery of 50 pounds of pasta was a first, said Cabahug.

As they walked in with a large container, the Straw-Ghetti duo saw needy men and women with scraggly hair and dirty clothing standing in line waiting for a free meal. It meant a lot to them to see who their donation would impact.

“It’s rewarding,” said Melville, who began a habit of giving to the poor years ago while donating untouched leftovers from his cousin’s catering business. “Instead of just tossing things away, it can go to somebody less fortunate, that can actually use it, and who needs it.”

Cabahug was quick to add that Pope Francis’ 2015 encyclical Laudato Si’ emphasizes care for the planet includes care for the people living on it.

Contrary to “the throwaway culture,” she said, “we can be more conscious about the people we help and make (the planet) better for everyone.”

The Pope’s Laudato Si’ has inspired many Catholics to think a bit more about the environment. They’ve made significant changes, including at The Door is Open.

Caring for the planet

“Ever since the Pope’s encyclical came out all about our common earth, our common home … we’ve transitioned from Styrofoam cups and plastic cups to compostable cups, bowls, paper plates, and (compostable) spoons and forks,” said Cabahug.

In fact, all the archdiocese’s Catholic Charities have made a concerted effort to reduce waste, reuse, recycle wherever possible, and find other ways to reduce their impact on the planet while ministering to the needy.

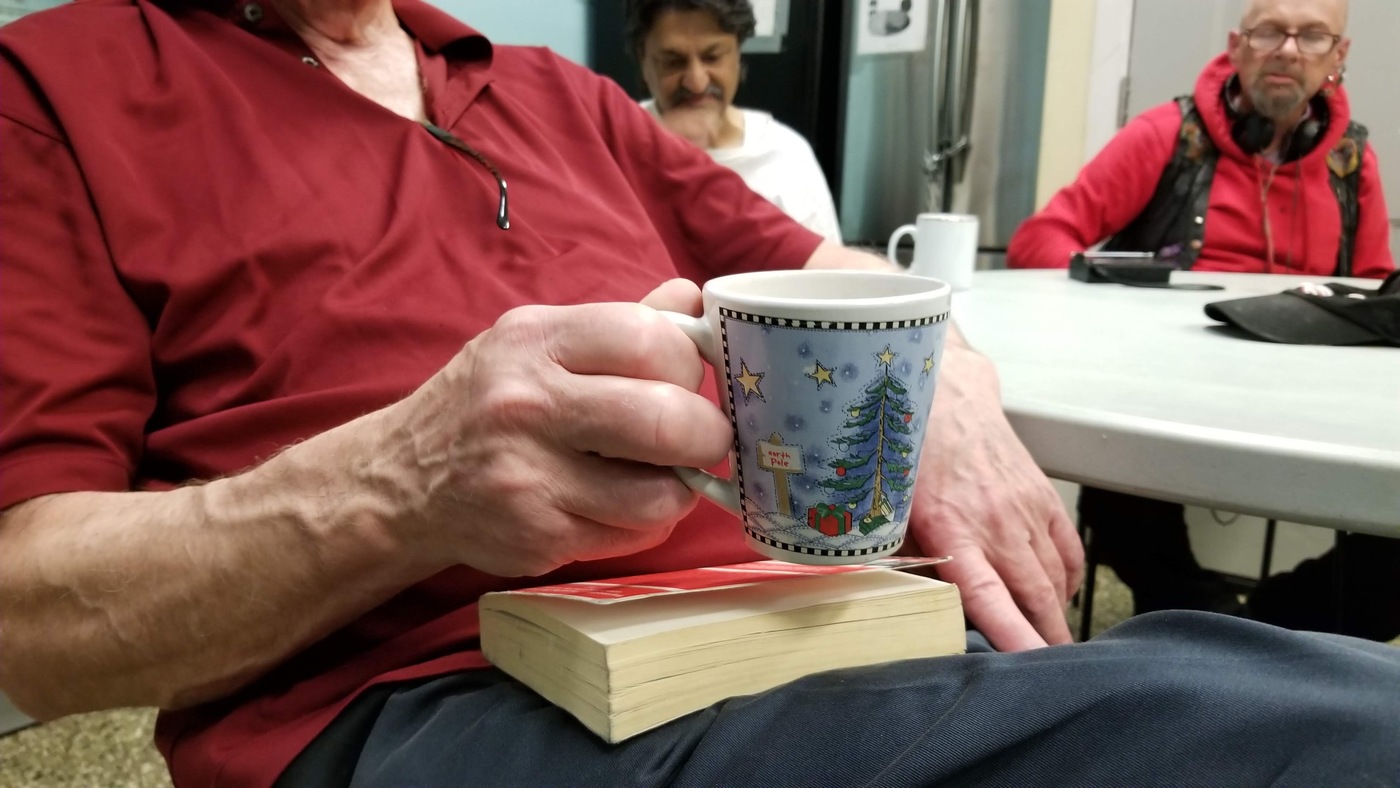

Catholic Charities Men’s Hostel at Cambie and Robson offers hot beverages, meals, and a safe place to sleep to 120 homeless or transient men each night. It also serves food on real dishes and coffee in ceramic mugs.

By abandoning single-use items, “we literally reduced our waste going to the landfill by two thirds,” said director Scott Small. A decade ago, the hostel would produce three dumpsters’ worth of trash per week. That’s dropped down to one since making the switch to real mugs and biodegradable cutlery from Styrofoam cups and plastic utensils.

“It was an easy piece of low-hanging fruit,” Small said.

And the rewards keep coming. Besides the benefits of reducing waste, his calls for donations of mugs have have blossomed into great relationships with schools and parish groups who have generously responded, happy to find a way to help the homeless.

Meanwhile, Catholic Charities Justice Services (better known as the archdiocese’s prison ministry) encourages its volunteers to go paperless, reduce plastic use, use real dishes at meetings, and carpool to prison visits. They have been doing so for about the last two years.

Getting ahead

These efforts put Catholic Charities miles ahead of the City of Vancouver, which was set to ban plastics and foams by June 1, 2019, but extended the deadline to 2020 to give businesses more time to transition.

They’re also ahead of federal policies; this month, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said the government will ban single-use plastics as early as 2021.

“We need to cover all of Canada with this decision and that’s why the federal government is moving forward on a science-based approach to establishing which harmful single-use plastics we will be eliminating as of 2021,” Trudeau said.

“Whether we’re talking about plastic bottles or cellphones, it will be up to businesses to take responsibility for the plastics they're manufacturing and putting out into the world.”

But to keep a promise made at a recent G7 summit, Canada has until 2040 to reuse, recycle, or burn all of its plastics.

Most Canadians are already on board for this kind of change. A new study of 1,000 people done by Dalhousie University found 71 per cent of respondents supported banning single-use plastics.

However, across the board they also found the vast majority of Canadians were unwilling to pay more than 2.5 per cent extra for green alternatives.

Not about the money

Brascia and Melville of Straw-Ghetti try to operate their business with little waste. Their pasta straws, made simply from semolina flour and water, are fully compostable, as are the packages they are sold in.

“We’re being pro-active instead of reactive,” said Melville.

“Sustainable stuff just costs more, but if you’re helping the environment, it’s worth the extra cents,” added Brascia. “We’re going to pay for it later, so why not pay for it now?”

The initial cost of eco-friendly alternatives is higher, but at the hostel Small has found running a charity with the environment in mind can actually save money in the long run.

For example, buying and maintaining a dishwasher for thousands of ceramic mugs at his shelter has cost him about $12,000 over the last 10 years, but it has saved him the $3,500 per year he used to spend on Styrofoam.

Plus, while biodegradable cutlery is four times more expensive than plastic utensils, he’s saved on garbage disposal fees.

Small says his team is ahead of the curve. “I thought a lot of people were creative like we were,” he said. But at various meetings in Vancouver, he’s found many organizations in his sector “are still buying Styrofoam and plastic knives.”