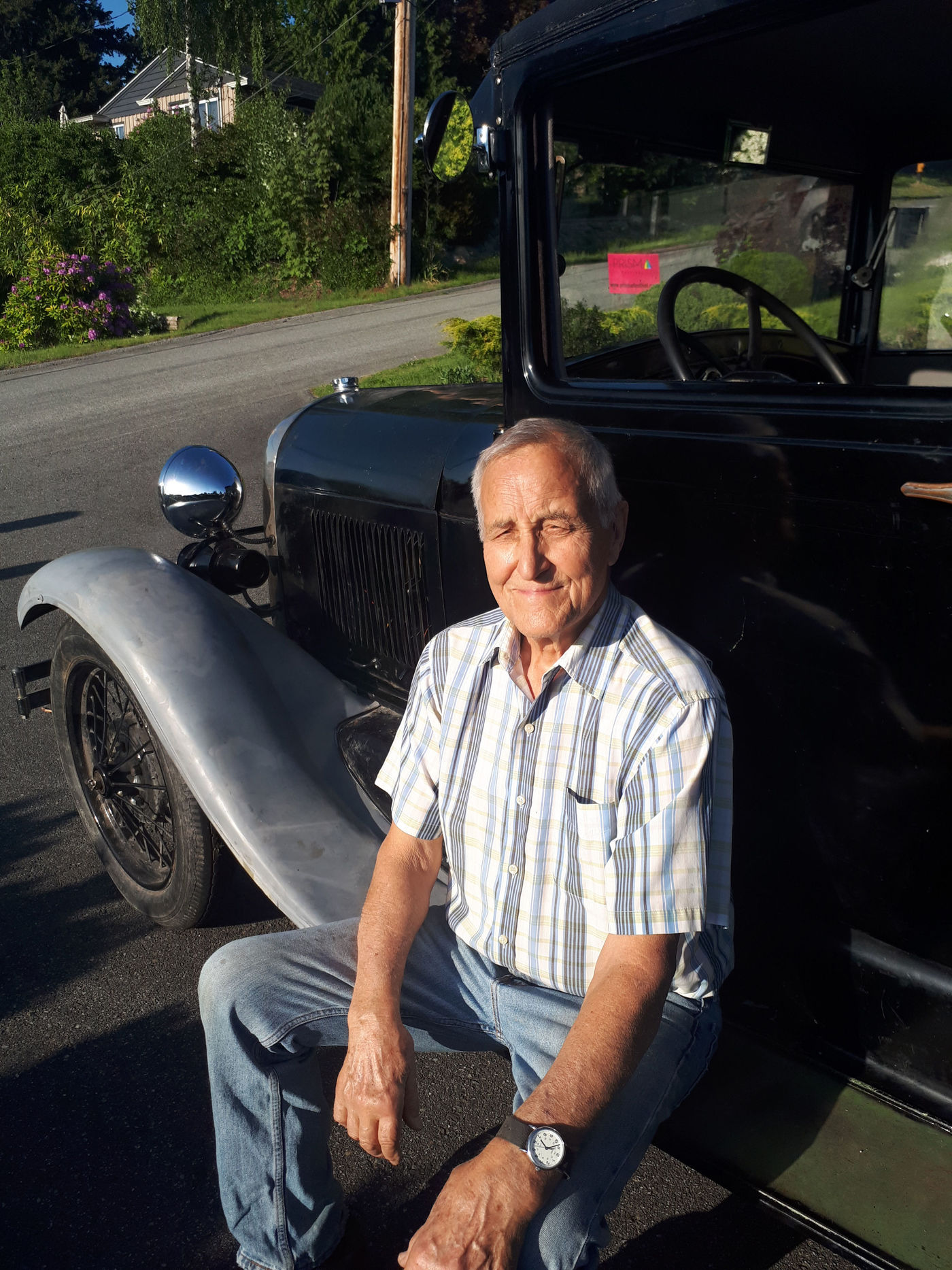

Powell River resident Brendan Allen repairs vintage cars as a tribute to the late priest who willed him a 1928 Model A Ford about 70 years ago. (Photos submitted)

Side by side in Brendan Allen’s Powell River driveway are his 1928 Model

A Ford and his futuristic Nissan Leaf.

Ethical and practical considerations explain the electric vehicle. But the Ford?

“I’m not a vintage car buff,” explained the 82-year-old retired construction business owner and pilot, wedging his lanky six-foot frame into the cramped driver’s seat. “I do this for sentimental reasons.”

For more than 60 years, Allen kept the matte black Model A – affectionately known as “Oh Henry” – in storage, first in the B.C. Interior, then at his home on Savary Island. After a full adulthood of marriage and family, building homes, flying, and finally retiring to Powell River, he moved it to his garage – and is currently bringing it back to life.

Model As are not rare. They were manufactured from 1927 until 1932, and five million of them rolled out of Ford’s factory. At just $385 US for a basic model, they were a steal – that’s about $7,500 in today’s Canadian dollars. Model As are a favourite among vintage car enthusiasts.

It’s been a project, since he hauled it out of storage. Rats infested the original upholstery. The paint was a mess.

These are problems he’s been fixing, in between delivering Meals on Wheels, Assumption Parish choir practice, lifting weights at the gym, and playing pool at the Legion. He hired a local upholsterer to train him; together, they completed one seat. He sewed the rest on his own. Now, he’s working on the exterior finish.

The former owner of the car was Father Michael Angelo “Matt” Phelan, Allen’s childhood priest and an Oblate teaching missionary. The gravel and mud roads of B.C.’s North Thompson Valley were the car’s first calling, carrying the remarkable priest from Mass to Mass – over a territory that included Merritt, Lytton, North Bend, Boston Bar, Spences Bridge, Ashcroft, Mamette Lake, Chu Chua, Barriere, Beresford and more, for 20 years between 1921 and 1941 – visiting the ill and elderly, and, often, picking up Brendan and his four tall, farm-isolated siblings, and driving them to church. The entire Irish-English family crammed in the tiny (by today’s standards) back seat.

Allen recalls working on the car with Father Phelan when he was very small – the priest, a former miner, had noticed his aptitude for mechanics. They repaired the car with whatever was at hand, including haywire, clothes pegs, and binder-twine. It often broke down. So, Father Phelan kept a bicycle in the backseat and would abandon the car when necessary and cycle the terrible, long and muddy roads to his next Mass or appointment.

Father Phelan stayed with the Allen family occasionally – once for three weeks in the winter when his own rough room was made uninhabitable by the cold.

“He didn’t go in for anything comfortable,” recalls Brendan. “People would give him chocolates and oranges at Christmas. They really were a luxury in those days. He’d give them all away, because he knew his parishioners were poor as church mice too.”

“If I ever knew a saint it is probably him,” said Brendan – high praise from someone who flew United Nations medical missions into Congo during the worst years of the civil war there. “He lived absolutely hand-to-mouth.”

Several books and newspaper articles corroborate Allen’s perceptions of the very dedicated Father Phelan. He’d been born in rural Cape Breton Island, in Little Bras d’Or. After a career in mining, he attended St. Augustine’s Seminary in Toronto, and was ordained at St. Michael’s Cathedral in 1919, at 39 years old. In the book North River: the Story of BC’s North Thompson Valley & Yellowhead Highway 5 (2000) Muriel Poulton Dunford writes, “Combining itinerant duties with the joy of out-of-doors, he planted trees by the churches and kept them alive by carrying buckets of water to them from the river. His practice of wearing a hat when he stopped for a swim in Dutch Lake seemed rather eccentric at the time, but current information about UV rays vindicates his good sense.”

On his retirement, the Merritt Herald wrote, “The priest was not known as a “community man,” unless the term community be stretched to take in ‘the jungle.’ The hungry and outcast have found in him a friend and a Father who would share his last loaf with an unfortunate – or give him the whole loaf. Not a worldly man in the usual meaning, Father Phelan was a missionary who puts self-sacrifice to the fore in his parish work. Among the sick he arduously nursed patients with helpful literature and kind deeds, regardless of their denominations. A hard man to really know, this was because of his whimsical humour and odd ways. Yet one does not need to know him well to feel that here is a man who gives every ounce of his energy physical and mental, towards the spiritual uplifting of his fellow human beings.”

The priest died in 1949, and he willed the Model A to Allen. The then-14-year-old travelled to Barriere, where “Oh Henry” was stored, and drove it home. He drove it around the ranch, and then parked it when he moved away in the mid-1950s.

“This rebuild was just something I felt like I should do to honour the old man who left it to me all those years ago.”

Church of the Assumption Pastor Father Patrick Teeporten provided many resources about Father Phelan for the purposes of this article.