Pope Francis greets Cardinal Stanislaw Rylko, president of the Pontifical Council for the Laity, during a meeting with members, consulters, employees and their family members of the council at the Vatican in 2016. The dicasteries, or agencies, of the Roman Curia include the secretariat of state, congregations, tribunals, pontifical councils, and offices, all of which are juridically equal. (Handout / L'Osservatore Romano)

Many readers have asked me to describe how the Pope governs the Catholic Church taking into consideration that the Vatican is an independent and sovereign state.

The Pope implements his judicial, legislative and executive office through an enormous complexus of bureaus called the Roman Curia. Although it really exists and acts only insofar as he wants it to, its specific powers are set out in the Code of Canon Law.

It includes the papal court and its functionaries, especially those through whom the government of the Roman Church is administered. The most important reformer of the old Curia was St. Pius X. Other changes were made by Paul VI in 1967 and then by St. John Paul II with the apostolic constitution, Pastor Bonus, of June 28, 1988.

The history of the Curia can be traced through three periods. From the first to the 11th century, the popes exercised their rule through synods – the presbyterium apostolicae sedis – composed of the clergy of Rome. At first, priests and deacons were consulted at these gatherings. Later on, from about the sixth century, the priests of principal churches or titles (the first cardinals) and the seven regional deacons of the city composed the synod together with the pope.

During the 11th century, the authority of the Roman synod and presbyterium was transferred gradually to the consistory, made up exclusively of cardinals. Alexander III, in 1170, laid down specific rules governing concistorial meetings, and other popes, notably Innocent III, further regulated their power. In later centuries, the complexities of papal administration necessitated further modifications.

By his celebrated bull Immensa (January 22, 1588), Sixtus V both created and regulated all those bureaus that, in one form or another, are still in existence today.

With respect to its organization, Pope John Paul II, on June 28, 1988, promulgated the apostolic constitution Pastor Bonus, to take effect on March 1, 1989, modifying the organization and competencies of the Roman Curia, which had been regulated by the norms of the August 15, 1967, apostolic constitution Regimini Ecclesiae Universae issued by Pope Paul VI.

The introduction to the new norms highlights the nature of the Curia as an aid to the Petrine ministry in service to the universal Church as well as to the bishops throughout the world and suggests that this reorganization of the Curia makes it conform more closely to the needs of the post-conciliar Church as well as to the exigencies of modern times, as the Code of Canon Law says.

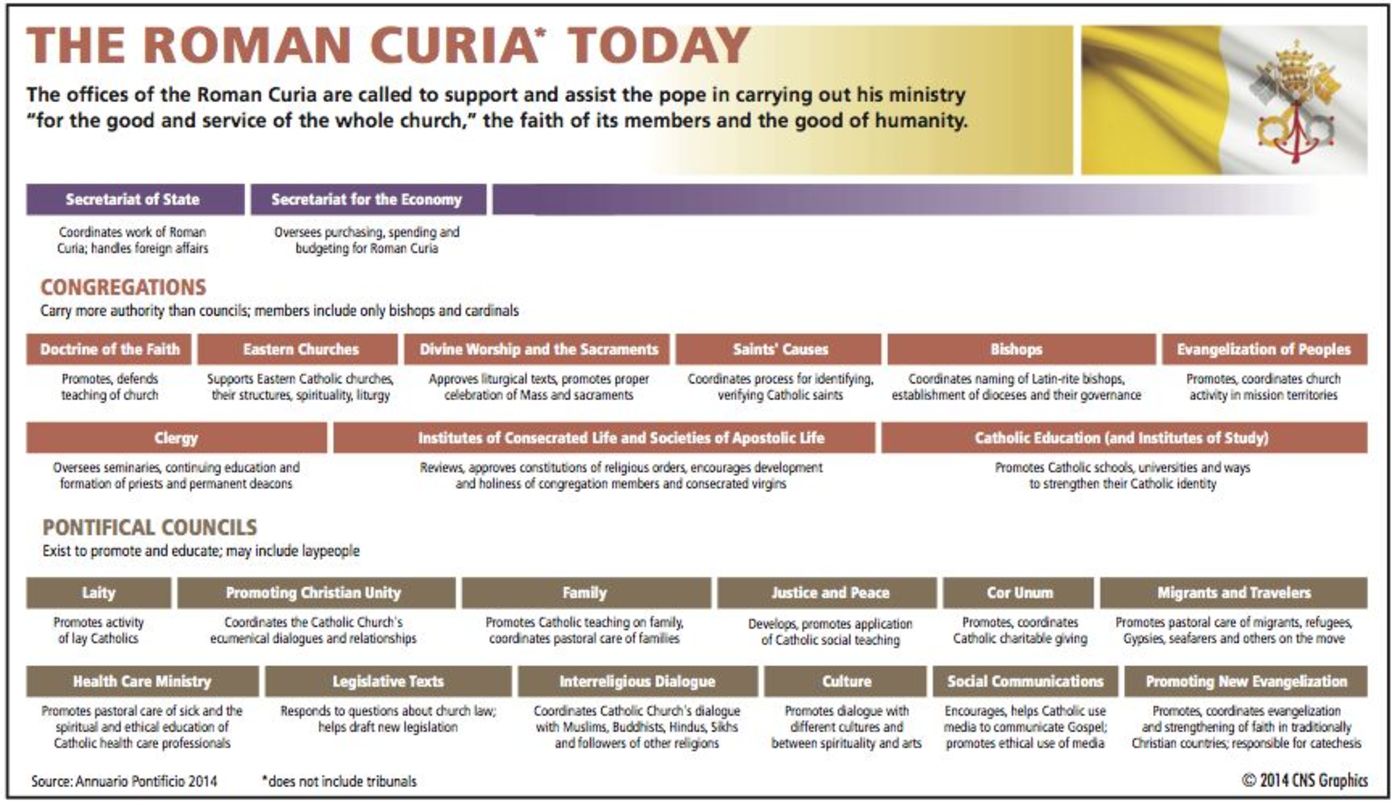

The dicasteries, as the various agencies of the Curia are called, include the secretariat of state, nine congregations, three tribunals, 12 pontifical councils, and three offices, all of which are juridically equal.

Other institutes attached to the Curia or related to the Holy

See include the prefecture of the pontifical household, the office of the

liturgical celebrations of the pope, the advocates for various tribunals and

dicasteries, and other important entities such as the Vatican secret archives,

and the Vatican library, press, radio and television.

There are about 2,000 residents in Vatican City – about 150 cardinals, bishops and priests, maybe 45 nuns, and 500 lay people, many married with families. There are many institutions, for instance the Teutonic College, with about eight priests and five nuns. The mosaic that makes up this fabric also includes a pharmacy, a supermarket, and a gas station. There is no tax on purchases made within the Vatican.

Cardinals and bishops, some residing in Rome and others in various parts of the world, comprise the actual membership of the different congregations. They are assisted in their work by secretaries, consultors, administrators, and other officials, both clergy and laity. All Curia members and officials are named for five-year terms. The dicasteries of the Curia deal with matters beyond the competence of bishops or groups of bishops, as well as with items reserved to the Holy See or committed to them by the pope.

No general decrees issued by dicasteries have the force of law or derogate laws unless given specific approbation by the pope, and no extraordinary business is to be handled by them without his cognizance.

All the dicasteries are to foster a good relationship with individual dioceses by communicating with the bishop of a diocese before issuing documents that concern matters therein and by responding expeditiously to requests made of them. Bishops’ ad limina visits are presented as a prime opportunity for fostering good relationships between bishops and the dicasteries of the Curia, while a central labour office handles all questions connected with employment in the Curia.

Another very important figure of the pontifical command is its constitution of the diplomatic corps. The Holy See has, around the world, 192 embassies called nunciatures, from the Latin “nuncius,” meaning “messenger.”